Top White House officials and Republican lawmakers struck a deal Thursday that would raise the two-year debt limit while imposing strict caps on discretionary spending not related to the military or veterans for the same period. Officials scrambled to reach an agreement in time to avoid a federal bankruptcy expected in just a week.

The deal taking shape would allow Republicans to say they were cutting some federal spending — even if spending on the military and veterans programs continued to grow — and allow Democrats to say they are cutting most of the domestic programs had spared significant budget cuts.

Negotiators from both sides continued to talk into the evening and began drafting legal texts, although some details were still in flux.

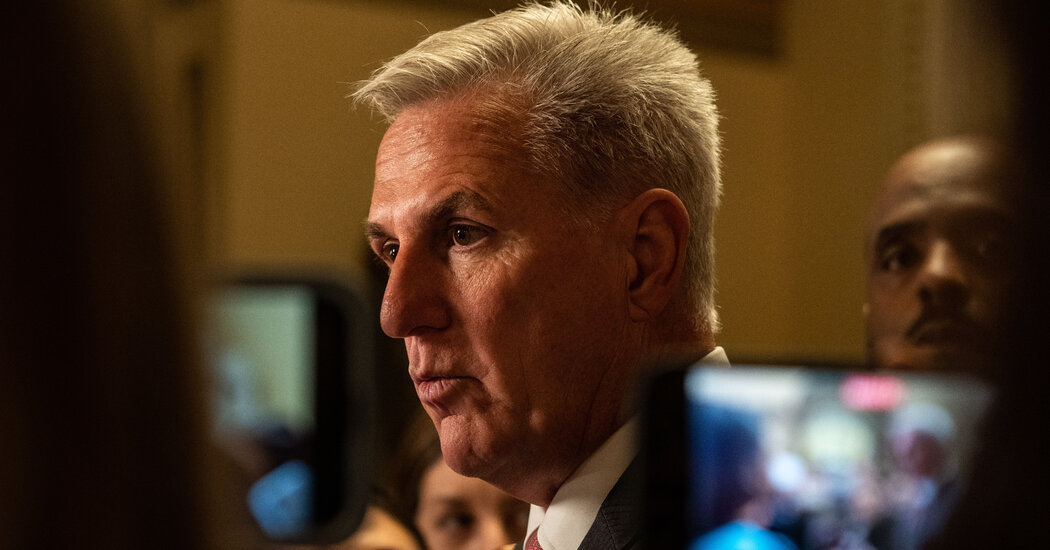

“We’ve been talking to the White House all day, we’ve been going back and forth, and it’s not easy,” Speaker Kevin McCarthy told reporters as he left the Capitol Thursday night, refusing to reveal what was under discussion. “It takes a while to get it done and we’re working hard to get it done.”

The compromise, if it can be agreed and passed, would raise the government’s borrowing limit for two years, after the 2024 election, according to three people familiar with it who insisted on anonymity to discuss a plan still in the making. the make was.

The United States hit the legal limit, currently $31.4 trillion, in January and has since relied on accounting measures to avoid default. The Treasury Department has predicted that it will exhaust its ability to pay bills on time as early as June 1.

In exchange for lifting the debt limit, the deal would meet Republicans’ demands to cut some federal spending, albeit with the help of accounting maneuvers that would give both parties political cover for a deal that is unlikely to be popular with large segments. of their constituents.

It would impose limits on discretionary spending for two years, though those limits would apply differently to spending on the military than to non-defense discretionary spending. Spending on the military would grow next year, as would spending on care for some veterans that fall under non-defense discretionary spending. The rest of nondefense discretionary spending is expected to fall slightly — or stay about the same — compared to this year’s levels.

The deal would also reverse $10 billion of the $80 billion Congress approved last year for an IRS crackdown on high earners and tax-dodging companies, though that provision was still under discussion. Democrats have defended the initiative and nonpartisan scorers have said the funding would reduce the budget deficit by helping the government collect more of the tax revenue owed. But Republicans have denounced it, falsely claiming the money would be used to fund an army of accountants to go after working people.

“The president and his negotiating team are fighting hard for his agenda, including IRS funding, so that it can provide better customer service to taxpayers and act against wealthy tax evaders,” White House spokesman Michael Kikukawa said in a statement Thursday. e-mail. in response to a question about the facility.

As the deal stood on Thursday, the IRS money would essentially shift to non-defense discretionary spending, allowing Democrats to avoid further cuts to programs such as education and environmental protection, according to people familiar with the pending agreement.

The plan had yet to be finalized and negotiators continued to negotiate crucial details that could make or break a deal.

“Nothing gets done until you actually have a full deal,” said North Carolina Representative Patrick T. McHenry, one of the lead GOP negotiators, who also declined to discuss the details of the negotiations. “Nothing has been resolved.”

The package’s cuts were almost certainly too modest to win the votes of hard-line fiscal conservatives in the House. Liberal groups were already lamenting Thursday about the reported deal to cut the increase in IRS funding.

But people familiar with the evolving deal said negotiators had agreed to fund military and veterans programs at the level President Biden envisioned in his budget for next year. They would cut non-defense discretionary spending below this year’s levels, but much of that cut would be covered by the shift in IRS funding and other budgetary maneuvers. White House officials have argued that those shifts would functionally make nondefense spending next year the same as this year.

All discretionary spending will then grow by 1 percent in 2025, after which the limits will be lifted.

Mr McCarthy had on Thursday agreed with the idea that a compromise to avoid bankruptcy would most likely draw opponents from both sides.

“I don’t think everyone will be happy at the end of the day,” he said. “That’s not how this system works.”

Another provision of the deal is designed to avoid a government shutdown later in the year, and would try to deprive Republicans of the ability to make deeper cuts to government programs and agencies later in the year through the appropriation process.

Exactly how such a measure works, remained unclear on Thursday evening. But it was based on a penalty of sorts, which would adjust spending ceilings in the event that Congress failed to pass all 12 standalone spending bills that fund the government by the end of the calendar year.

Negotiators continued to disagree on work requirements for social safety net programs and a review of permits for domestic energy and gas projects.

“We have legislative work to do, policy work to do,” Mr McHenry said. “The details of all those things are really important for us to get this thing through.”

As negotiators moved closer to a deal, far-right Republicans grew increasingly fearful on Thursday that Mr McCarthy would sign a compromise they deemed insufficiently conservative. Several right-wing Republicans have already vowed to oppose any compromise that waives spending cuts that were part of their debt curtailment bill.

“Republicans shouldn’t make a bad deal,” Texas Representative Chip Roy, an influential conservative, wrote on Twitter Thursday morning, shortly after telling a local radio station that he should “have some blunt conversations with my colleagues.” and the leadership team” because he didn’t like “the direction they’re going”.

Representative Ralph Norman, Republican of South Carolina, said he would reserve his verdict on how he would vote on a compromise until he sees the bill, but added, “What I’ve seen now isn’t good.”

Former President Donald J. Trump, who has said Republicans should force a default if they don’t get what they want in the negotiations, also weighed in. Mr McCarthy told reporters he spoke briefly with Mr Trump about the negotiations – “it only came up for a moment,” the speaker said. “He was talking about, ‘Get a good deal.'”

After playing a tee shot on his golf course outside of Washington, Mr. Trump approached a reporter from The New York Times, iPhone in hand, and showed a phone call with Mr. McCarthy.

“It’s going to be an interesting thing — it’s not going to be that easy,” Trump said, describing his call with the speaker as “a short, quick conversation.”

“They’ve wasted three years of money on bullshit,” he added, saying, “Republicans don’t want to see that, so I understand where they stand.”

Luke Broadwater And Stephanie Lay contributed reporting from Washington. Alan Blinder contributed reporting from Sterling, Va.