BANGOR, Maine (AP) — Operators of illegal marijuana grow houses in rural Maine homes don’t have to worry too much about nosy neighbors. But their staggering electric bills could give rise to a new snitch.

An electric utility has made an unusual proposal to help law enforcement crack down on illegal activity, which is being investigated for links to transnational crime. But critics fear the move would violate customer privacy.

More than a dozen states that have legalized marijuana have seen a spike in illegal marijuana grow operations that use vast amounts of electricity. And Maine’s Versant Power has received subpoenas — sometimes for 50 locations at a time — from law enforcement, said Arrian Myrick-Stockdell, a corporate lawyer. A far more effective way, he suggested to utility regulators, would be to flip the script and allow utilities to report their suspicions to law enforcement.

“Versant has a very high success rate in identifying these locations, but we have no ability to proactively communicate with law enforcement,” Myrick-Stockdell told commissioners.

The proposal, which will be considered next week by the Maine Public Utilities Commission, has been criticized by consumer privacy advocates and others who say the utility is overstepping the mark.

The nonprofit Electronic Privacy Information Center argues that such a rule would be unconstitutional because it would allow the utility to provide private information about consumers “without probable cause, without a warrant, without judicial review,” Alan Butler, the group's executive director, told The Associated Press.

The Washington-based group has never heard of such a proposal, he said, even though federal courts have authorized the sharing of consumer data from so-called “smart” electricity meters for the limited purpose of managing the electric grid.

Jay Stanley, a privacy expert with the American Civil Liberties Union, compared a utility company that searches through customer data to an illegal dragnet. “Utilities shouldn’t be doing that. They have a duty to protect the privacy of their customers,” he said.

Historically, courts have applied special privacy protections to what happens inside a home.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2001 that federal agents' use of thermal imaging equipment without a search warrant to detect the heat from marijuana grow lights in an Oregon man's home was unconstitutional.

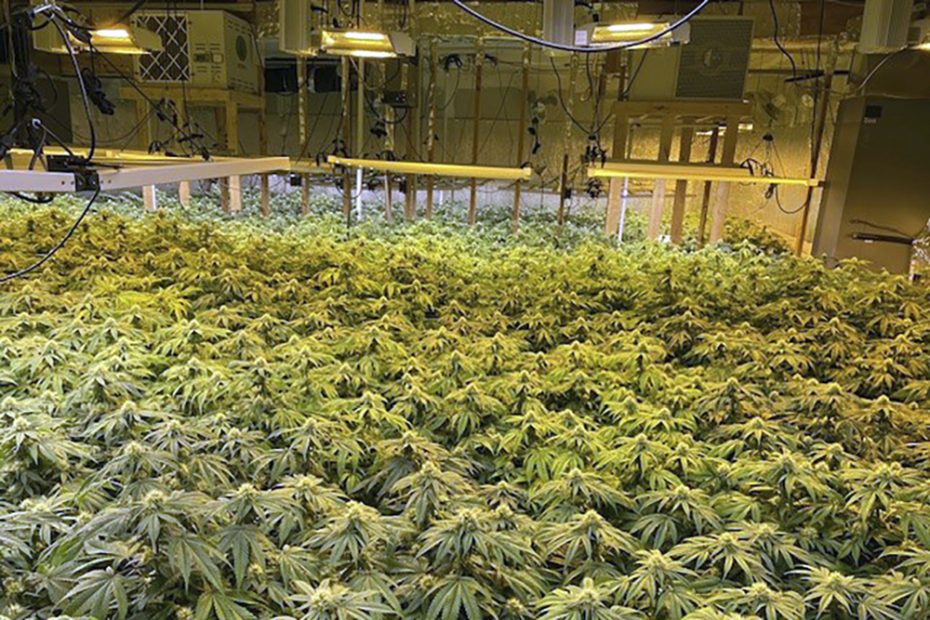

The lawsuit against Maine utilities comes as law enforcement targets marijuana grow operations, buying up rural homes, gutting them and converting them into sophisticated, high-production indoor farms.

In total, 20 states are dealing with phenomena similar to what is happening in Maine.

The common denominator is that criminals appear to be taking advantage of marijuana legalization laws in an attempt to fly under the radar and produce marijuana that is sold in states where cannabis is illegal. The FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration are investigating whether these operations have ties to criminal syndicates, including Chinese organized crime.

In Oklahoma, farms, vacant nursing homes, bowling alleys and warehouses were turned into marijuana production facilities after voters legalized cannabis for medical use in 2018. Law enforcement stepped up its crackdown after realizing that front men in China and Mexico were running many of the licensed businesses, said Mark Woodward, spokesman for the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics.

In Maine, things are different, with purchases of cheap homes in remote locations, installation of energy-guzzling grow equipment and upgraded electrical services to support the operations. Law enforcement has taken notice of that power consumption. At one of the homes burglarized in Maine, the monthly electric bill went from about $300 to nearly $9,000, according to court documents. At one point, there were more than 100.

The grow houses operate according to a similar playbook in terms of the types of homes used and the indoor setups with powerful lights, climate control and chemicals. However, they are not linked together like a typical franchise agreement, making it difficult for law enforcement to tie them to a single syndicate, Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Lizotte told The Associated Press.

In Somerset County, Sheriff Dale Lancaster, whose officers have executed search warrants on 21 marijuana businesses, said law enforcement works best with community support. He described Versant's proposal as a “good first step.”

Republican Sen. Susan Collins, who has aggressively challenged the FBI on illegal marijuana operations, also supports Versant's efforts to ally with law enforcement. “Collaboration between Maine's electric utilities and law enforcement could be a tremendous help to the county sheriffs and other officials who have worked tirelessly to crack down on these illegal grow operations,” she said.

Versant's proposal was discussed earlier this year by the Maine Public Utilities Commission.

Derek Davidson, a member of the committee, mused about the possibility of a threshold for reporting spikes in electricity consumption to police, but noted that sometimes there are legitimate users “who are just consuming astronomically.”

Mark Morisette of Central Maine Power said it “seems like a scary line to even consider crossing” and backed his call for caution with an example of a 100-fold increase in electricity use after a flood, requiring temporary heaters and fans to dry it out.

CMP, the state's largest electric utility, is now formally opposing the change but will continue to fully cooperate with law enforcement if subpoenaed for customer data, spokesman Jonathan Breed said.

Maine Public Advocate William Harwood also opposes the proposal, arguing that there are too many legitimate reasons for increased customer consumption, such as the installation of heat pumps and electric vehicle charging stations. “We believe utilities should focus on consumer needs and consumer service, rather than alerting law enforcement to questionable customer behavior,” he said.