The US economy generated solid job growth in March, but at a slowing pace that seemed to reflect the toll from steadily rising interest rates.

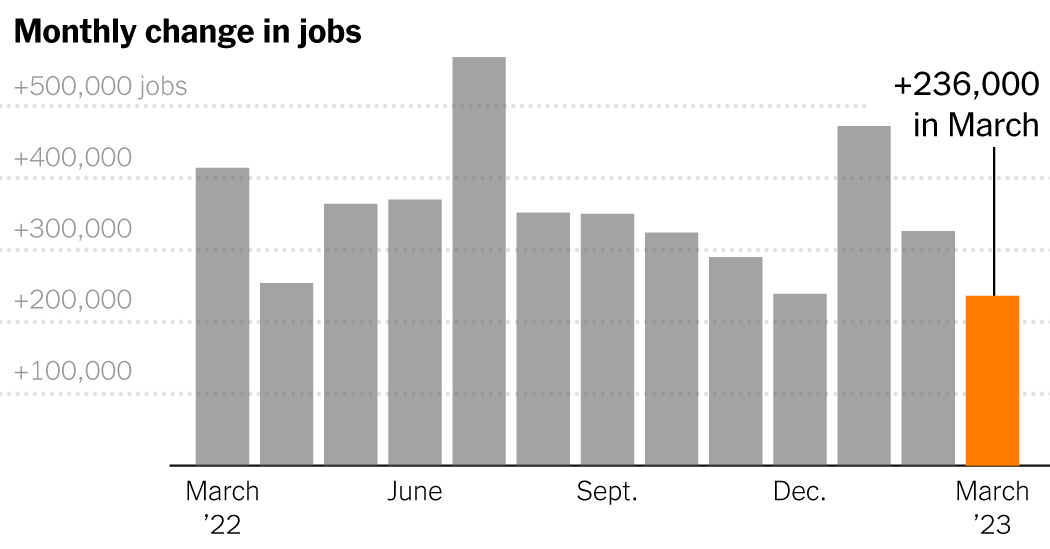

Employers added 236,000 jobs in the month on a seasonally adjusted basis, the Labor Department reported Friday, against an average of 334,000 jobs added in the previous six months. The unemployment rate fell from 3.6 percent in February to 3.5 percent.

Year-over-year growth in median hourly wages also slowed, to 4.2 percent, the lowest rate since July 2021 — a sign the Federal Reserve was looking to quell inflation. And the average work week became shorter as the staff shortage eased, forcing employees to work extra hours.

Preston Caldwell, chief US economist at Morningstar Research, said the data offered new hope that the Fed could cool the economy without triggering a recession. “It seems that the range of options bordering on what we might call a soft landing is expanding,” he said. “Wage growth has now largely normalized without a huge rise in unemployment. And a year ago, many people would not have predicted that.”

The report provided welcome news for President Biden, who has been saying for more than a year that job creation needs to be slowed to about 150,000 jobs a month to curb the rapid rise in consumer prices and restore a sense of economic stability. Mr Biden has tried to balance the celebration of strong job growth with reassurance that inflation is beginning to cool.

With markets closed for Good Friday, bond traders generated the most reaction from investors. Yields rose on confidence that the economy remains robust enough for the Fed to continue with further rate hikes.

Inflation FAQs

What is Inflation? Inflation is a loss of purchasing power over time, meaning your dollar won’t go as far tomorrow as it did today. It is usually expressed as the annual change in prices for everyday goods and services such as food, furniture, clothing, transport and toys.

Even as job creation ebbs, the labor market has achieved something remarkable: the lowest ever unemployment rate for black workers, at 5 percent, representing the smallest gap ever between the numbers for black and white people. Historically, marginalized workers tend to take a different look when recruiters have more vacancies to fill.

Nevertheless, forecasters expect a marked slowdown in growth later in 2023, which could lead to more pink slips as profits erod and companies choose to lay off workers.

March’s employment data, reflecting a 27th consecutive month of growth, was collected before two medium-sized banks failed and concerns arose about other financial institutions. That turn of events is expected to tighten lending across the economy, potentially curbing consumer spending and curbing the growth potential of smaller firms.

The Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates for more than a year to curb inflation, but bank outbursts are complicating that effort. If the reaction is strong enough, it could even increase the likelihood of a deep recession.

Fed officials raised rates at their most recent meeting on March 22 and predicted they could raise them again this year. Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell underlined that the central bank could do more or less depending on the severity of the impact.

The March report provides the latest monthly jobs data ahead of the next Fed meeting in early May.

Contractions are already visible in a growing number of sectors as retail, manufacturing, construction and real estate finance – which are more sensitive to borrowing costs – lost jobs or remained flat during the month.

Other fast-growing sectors, including hospitals, hotels and restaurants, eased somewhat. Overall, leisure and hospitality employers remain 2.2 percent below their prepandemic headcount; a full recovery may be a long way off.

In a sign of things to come, job openings fell sharply in February, bringing the number of vacancies per available worker to a level that, while still high, is closer to the historical average. Surveys from both manufacturers and service companies came out weaker than expected this week, with more employers beginning to say business is shrinking rather than growing.

“There are only a handful of ways to go about that, and the main one is to reduce the workforce,” said Thomas Simons, an economist at investment bank Jefferies. “Although companies have struggled very hard to fill vacancies, it should be done by the end of the summer.”

Over the past year, layoffs across the economy had remained low as workers voluntarily quit their jobs and companies held on to anyone who wanted to stay. But that is starting to change.

Initial claims for unemployment insurance are on the rise, according to data released Thursday, after the Department of Labor revised the numbers to better reflect seasonal factors. A survey of layoff notices collected by the outplacement agency Challenger, Gray & Christmas found that job losses increased 15 percent in March, tripling from a year earlier.

Part of that contraction reflects an adjustment by companies in areas like trucking and warehousing that sucked workers in when business boomed during the height of the pandemic, and are now trying to bring payrolls more in line with declining revenues.

“They were so busy that they just had to throw people at the problems,” says Melissa Hoegener, director of recruiting at SCOPE Recruiting, a company in Huntsville, Alabama, that focuses on supply chain and logistics personnel. “Now that things are stable, they can sit back and say, ‘Hey, do we need that many people? We can automate this warehouse or outsource our shipping and receiving and really save money.’”

The state of affairs in the United States

Those hit by high-profile budget cuts at Silicon Valley giants like Google and Meta have plenty of options. While industries like utilities and insurance may not pay as much, the sudden availability of workers with tech skills is a huge boost.

“That meets much of the pent-up demand for these very highly skilled technology workers,” said Toby Dayton, CEO of employment data firm LinkUp. “The layoffs are hugely beneficial for everyone because it really adds to this soft landing.”

Other employees won’t have an easy time replacing lost work.

For example, construction employment appears to be stagnating as high mortgage rates deter buyers and builders struggle to finance commercial projects. Unlike software developers, those who pour concrete and hang drywall cannot take jobs elsewhere without moving.

And just as some employers are starting to cut back, more people are looking for work.

The number of people working or looking for work rose by 480,000, bringing the overall participation rate to 62.6 percent. That’s still below the prepandemic level of 63.3 percent as more people reach retirement age. The participation rate of people in their prime working years has fully recovered, although women are bouncing back faster than men.

The forces that drive people back to the labor market are complex. Returning to work has become feasible for some as school schedules have become more regular, childcare staff numbers have grown back and employers have responded to calls for more paid time off and flexible schedules. The number of women citing family responsibilities for not working has fallen by half in the past year.

For others, inflation itself has been a major factor, as rising prices have eaten away at all the savings accumulated during the pandemic, prompting many to look for work. In addition, higher wages and better benefits, created by years of labor shortages, have made some jobs more attractive.

Tessa Jameson works as a waiter at an Italian restaurant in San Francisco and tends the bar at a local dive shop while pursuing a college degree that she couldn’t afford after high school. That could pave the way for a career in landscape architecture, but Ms Jameson said she wouldn’t mind staying in the service industry as labor demand across the board had brought improved conditions and wages.

“What has happened between pre-Covid and now has created a culture that I feel more ethically comfortable participating in,” said Ms Jameson, noting that she had more respect for restaurant staff. “If things took a turn for the worse, I’d be much more eager to leave.”

Jim Tankersley, Jeanna Smilek And Joe Rennison reporting contributed.