Millions of US military emails have been misdirected to Mali in a “typo leak” that exposed highly sensitive information, including diplomatic documents, tax returns, passwords and the travel details of top officers.

Despite repeated warnings for a decade, a steady stream of email traffic continues to the .ML domain, the country identifier for Mali, as a result of mistyping .MIL, the suffix for all US military email addresses.

The problem was first identified nearly a decade ago by Johannes Zuurbier, a Dutch internet entrepreneur contracted to manage Mali’s land domain.

Zuurbier has been collecting misdirected emails since January in an attempt to persuade the US to take the issue seriously. He has nearly 117,000 misdirected messages – nearly 1,000 arrived on Wednesday alone. In a letter he sent to the US in early July, Zuurbier wrote: “This risk is real and could be exploited by opponents of the US.”

Control of the .ML domain will pass from Zuurbier on Monday to the government of Mali, which is closely affiliated with Russia. When Zuurbier’s 10-year management contract expires, Malian authorities will be able to collect the misdirected emails. The Malian government has not responded to requests for comment.

Zuurbier, general manager of Amsterdam-based Mali Dili, has repeatedly approached US officials, including through a defense attaché in Mali, a senior adviser to the US National Cyber Security Service and even White House officials.

Much of the email stream is spam and none are marked as classified. But some of the messages contain highly sensitive data about serving US military personnel, contractors and their families.

Their content includes x-rays and medical records, identity document information, ship crew lists, base personnel lists, installation plans, base photographs, naval inspection reports, contracts, criminal complaints against personnel, internal harassment investigations, official travel itineraries, bookings and tax and financial data.

Mike Rogers, a retired US admiral who formerly headed the National Security Agency and the US Army’s Cyber Command, said, “If you have this kind of sustained access, you can even generate intelligence from unclassified information.”

“This is not unusual,” he added. “It’s not uncommon for people to make mistakes, but the question is the scale, duration and sensitivity of the information.”

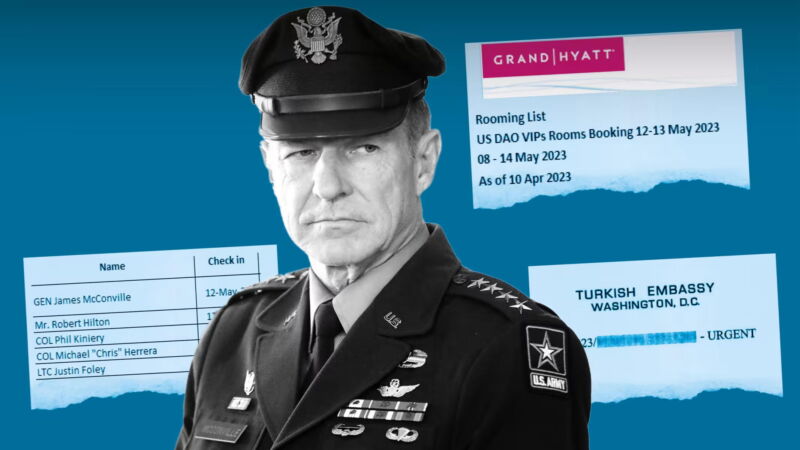

A misdirected email this year contained travel plans for US Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville and his delegation for a then-upcoming visit to Indonesia in May.

The email contained a full list of room numbers, the itinerary for McConville and 20 others, as well as details on how to collect McConville’s room key at the Grand Hyatt Jakarta, where he received a VIP upgrade to a grand suite.

Rogers warned that the transfer of control to Mali was a significant problem. “It’s one thing when you’re dealing with a domain administrator who tries, even unsuccessfully, to raise a concern,” said Rogers. “It’s another when it’s a foreign government that … sees it as an advantage they can use.”

Lieutenant Commander Tim Gorman, a spokesman for the Pentagon, said the Department of Defense “is aware of this matter and takes seriously any unauthorized disclosure of controlled national security information or controlled unclassified information.”

He said emails sent directly from the .mil domain to Malian addresses “are blocked before they leave the .mil domain and the sender is informed to validate the email addresses of the intended recipients.”

When Zuurbier, who has led similar operations for Tokelau, the Central African Republic, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, adopted Mali’s country code in 2013, he quickly noticed requests for domains such as Leger.ml and Marine.ml, which are not to exist. Suspecting that this was actually email, he set up a system to catch such correspondence, which was quickly overrun and stopped collecting messages.

Zuurbier says that after realizing what was happening and seeking legal advice, he repeatedly tried to warn US authorities. He told the Financial Times that he gave his wife a copy of the legal advice “in case the black helicopters land in my backyard”.

His efforts to raise the alarm included joining a trade mission from the Netherlands in 2014 to enlist the help of Dutch diplomats. In 2015, he made another attempt to warn US authorities, but to no avail. Zuurbier started collecting misdirected email again this year in a last-ditch effort to warn the Pentagon.

The data stream shows some systematic sources of leakage. Travel agents working for the military routinely misspell emails. Employees who send emails between their own accounts are also a problem.

An FBI agent with a naval position tried to forward six messages to their military email and mistakenly sent them to Mali. One contained an urgent Turkish diplomatic letter to the US State Department regarding possible operations by the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) against Turkish interests in the US.

The same person also forwarded a series of briefings on US domestic terrorism labeled “For Official Use Only” and a global anti-terrorism review headlined “Not to be released to the public or foreign governments.” A “sensitive” briefing about efforts by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to use Iranian students and the Telegram messaging app for espionage in the US was also included.

Gorman told the FT, “While it is not possible to implement technical controls to prevent the use of personal email accounts for government business, the department continues to provide direction and training to DoD personnel.”

About a dozen people falsely requested recovery passwords for an intelligence system that was to be sent to Mali. Others sent the passwords needed to access documents hosted on the Department of Defense’s secure file exchange. The FT has not attempted to use the passwords.

Many emails come from private contractors who work with the US military. Twenty routine updates from defense contractor General Dynamics related to the production of grenade training cartridges for the military.

Some emails contain passport numbers sent by the State Department’s Special Issuance Office, an agency that issues documents to diplomats and others traveling to the US on official business.

The Dutch army uses the domain Leger.nl, a keystroke away from Leger.ml. There are more than a dozen emails from serving Dutch personnel that include conversations with Italian counterparts about ammunition pick-ups in Italy and detailed exchanges about Dutch Apache helicopter crews in the US.

Others included discussions about future options for military procurement and a complaint about the potential vulnerability of a Dutch Apache unit to cyber attacks.

The Dutch Ministry of Defense did not respond to a request for comment.

Eight Australian Department of Defense emails intended for US recipients have gone astray. Those included a presentation on corrosion problems in Australian F-35s and a gunnery manual “carried by command post officers for each battery.”

Australia’s Department of Defense said it “does not comment on security issues”.

© 2023 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. May not be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.