Porcornie’s lawsuit is still pending. In December, the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights issued an interim judgment in which it strongly suspected that the software used by the VU was discriminatory and gave the university 10 weeks to put forward a defence. That defense has not yet been made public, but the VU has previously argued that Pocornie’s log data – which shows how long it took her to log into her exam and how many times she had to restart the software – imply that her problems were to blame to an unstable internet connection, as opposed to problems with facial recognition technology. A ruling is expected later this year.

Anti-cheat software producers like Proctorio got a boost from the pandemic, as exam halls were replaced by students’ own homes. Digital monitoring was intended to help schools and universities continue to operate as normal during the lockdown, without giving unsupervised students the opportunity to cheat. But the pandemic is over and the software is still being used, even as students around the world return to face-to-face teaching. “We don’t believe it will go away,” said Jason Kelly, who focuses on student surveillance at the US-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, in a December 2022 review of the state of student privacy.

In the US, Amaya Ross says her Ohio university still uses anti-cheating software. But every time she logs in, she fears her experience during the pandemic will be repeated. Ross, who is black, also says she couldn’t access her test when she first came across the software in 2021. “It just kept saying, we can’t recognize your face,” says Ross, who was 20 at the time. After receiving that message three or four times, she started playing with the nearby lights and the blinds. She even tried to take a test while standing, directly under her ceiling lamp.

She eventually found that if she balanced an LED flashlight on a shelf near her desk and pointed it straight at her face, she could pass her science test even though the light was nearly blinding. She compares the experience to driving at night with a car approaching from the other direction with the headlights on full beam. “You just had to keep going until it was done,” she says.

Ross refuses to name the company that made the software she still uses (Proctorio has sued at least one of its critics). But after her mother, Janice Wyatt-Ross, Posted about what happened on Twitter, Ross says a company representative reached out and advised her to stop taking whitewall tests. Now she’s doing tests with a multi-colored wall hanger behind her, which seems to be working so far. When Ross asked some of her black and dark-skinned friends about the software, many of them had experienced similar problems. “But when I asked my white friends, they said, ‘I do tests in the dark,'” she says.

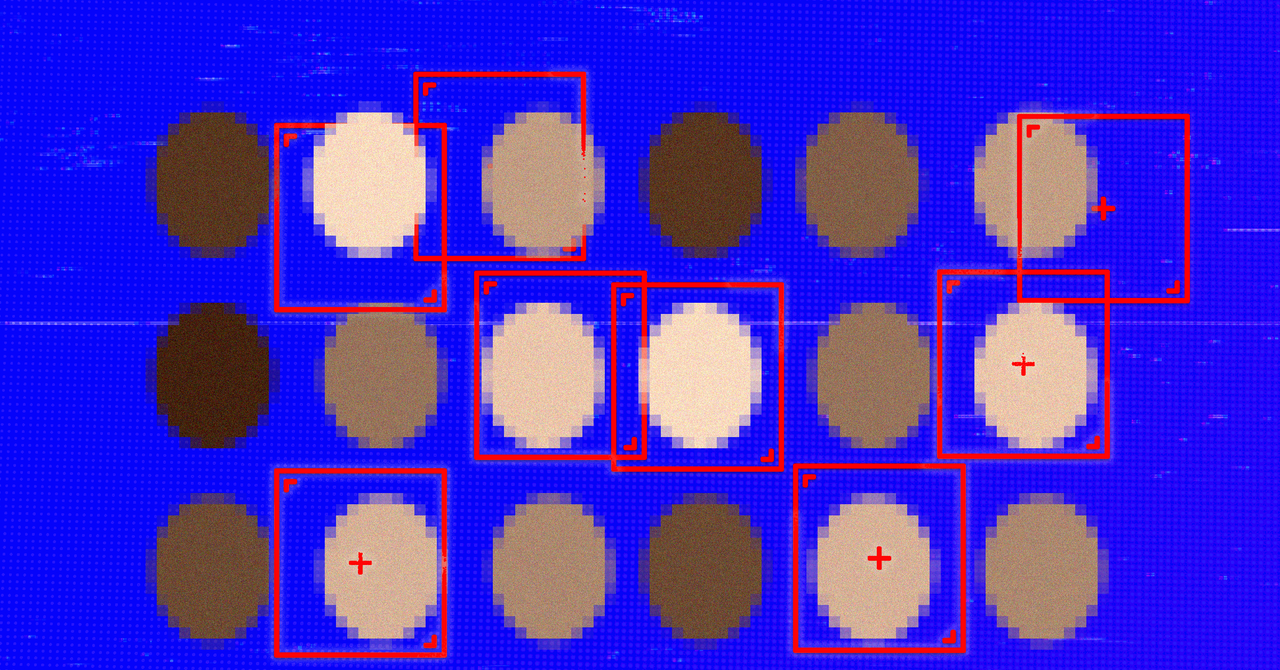

Typically, facial recognition and detection technology fails to recognize dark-skinned people when companies use models that aren’t trained on different datasets, says Deborah Raji, a Mozilla Foundation contributor. In 2019, Raji co-published an audit of commercially deployed facial recognition products, which found that some of them were up to 30 percent worse at recognizing dark-skinned women than white men. “A lot of the datasets that used to be commonly used in the facial recognition space [2019] contained more than 90 percent of the lighter-skinned subjects, more than 70 percent of the male subjects,” she says, adding that progress has been made since then, but this isn’t a problem that has been “solved.”