Jenny Nuss/Berkeley Lab

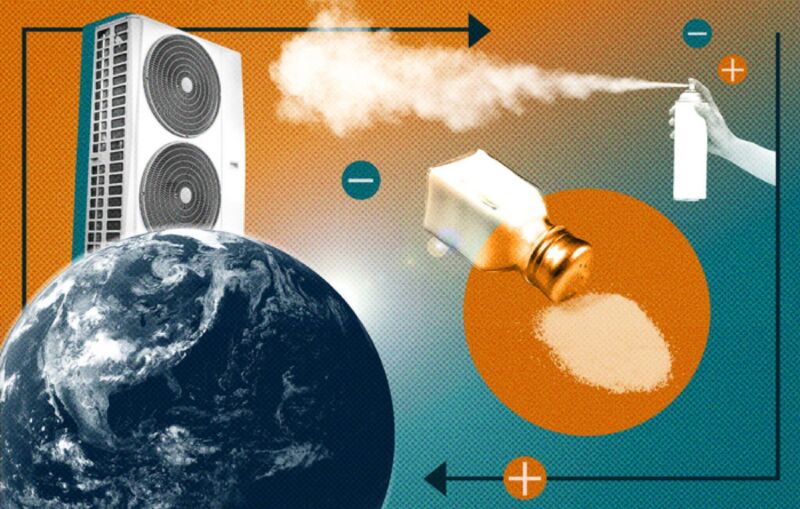

Scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have developed a new potential means of alternative cooling: ionocaloric cooling. The method involves electrically charged atoms or molecules (ions) that change the melting point of a solid material, much like adding salt to roads before a winter storm changes the way ice is formed. Their proof-of-principle experiment used salt made with iodine and sodium along with an organic solvent to achieve energy-efficient refrigeration, according to a recent paper published in the journal Science.

“The refrigerant landscape is an unsolved problem: no one has successfully developed an alternative solution that gets things cold, works efficiently, is safe, and doesn’t harm the environment,” said study co-author Drew Lilley. “We think the ionocaloric cycle has the potential to achieve all of those goals, if done properly.”

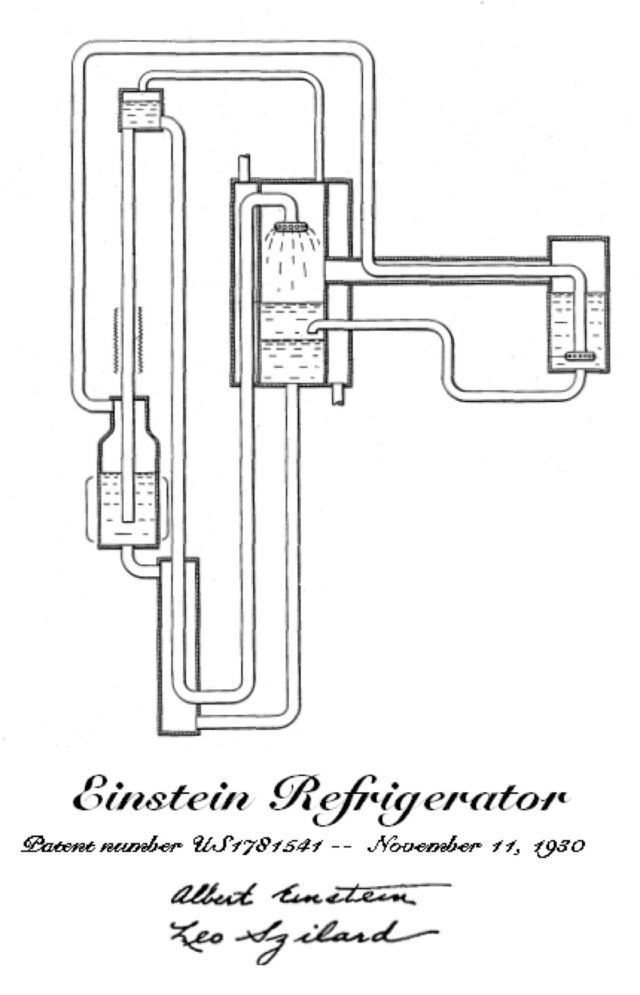

There’s a long history of scientists looking for better refrigeration alternatives, including a refrigerator designed by physicists Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard. The impetus for the collaboration between the two men came in 1926, when newspapers reported the tragic death of an entire family in Berlin as a result of toxic gas fumes leaking through the house while they slept – the result of a broken refrigerator seal. Such leaks became alarmingly common as more people replaced traditional coolers with modern mechanical refrigerators that relied on toxic gases such as methyl chloride, ammonia and sulfur dioxide as refrigerants. Einstein was deeply moved by the tragedy and told Szilard that there had to be a better design.

Einstein and Szilard turned their attention to absorption refrigerators, in which a heat source – at that time a natural gas flame – is used to drive the absorption process and release refrigerant from a chemical solution, rather than a mechanical compressor. An earlier version of this technology had been introduced in 1922 by Swiss inventors, and Szilard found a way to improve their design using his expertise in thermodynamics. Its heat source drove a combination of gases and liquids through three interconnected circuits: pressurized ammonia, butane and water, with no electricity required to operate the device (depending on the chosen heat source) and no moving parts.

On one side was a flask filled with butane (the vaporizer), which was injected just above the butane by a new vapor (the ammonia), creating that all-important difference. This would lower the boiling temperature, and as the liquid water boiled, it extracted energy from its surroundings, cooling the compartment. Einstein and Szilard’s refrigerator concept never became a commercial product. The introduction of the non-toxic refrigerant Freon in 1930 proved more economical.

Public domain