ÑFotógrafos Photography Study

Archaeologists have unearthed a 5,300-year-old skull from a Spanish grave and determined that seven lacerations near the left ear canal are strong evidence of a primitive surgical procedure to treat an infection of the inner ear. That makes this the earliest known example of ear surgery found to date, according to the authors of a recent paper published in the journal Scientific Reports. The Spanish team also identified a flint knife that may have been used as a cauterization tool.

The excavation site is located in the dolmen of El Pendón in Burgos, Spain, and consists of the remains of a megalithic monument dating back to the 4th century BC, i.e. the late Neolithic period. The ruins include an ossuary containing the bones of nearly 100 people, and archaeologists have been excavating those remains since 2016.

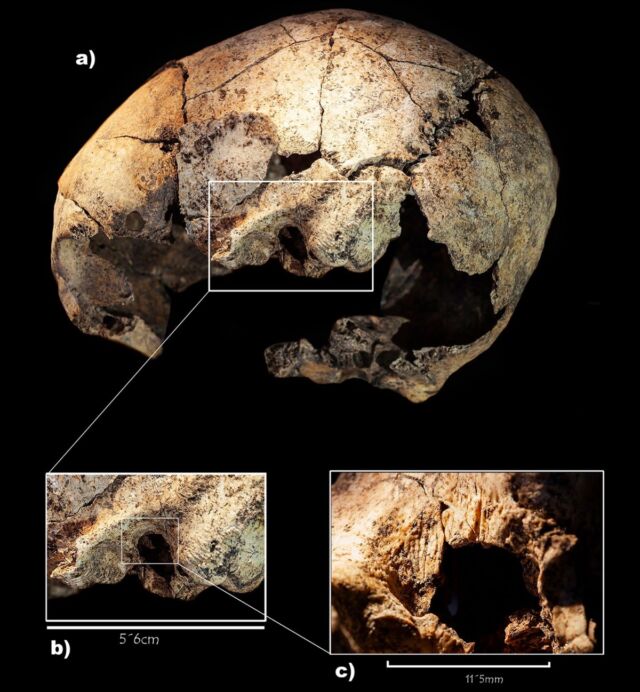

In July 2018, the team recovered the skull that is the subject of this latest study. The skull lay on its right side, facing the entrance to the burial chamber, and although most of the skull was intact, no teeth remained. The missing teeth, plus the loss of bone density and fully ossified thyroid cartilage, indicated that this was the skull of an elderly woman 65 years of age or older.

S. Diaz-Navarro et al., 2022

Evidence of perforations was found on both sides of the skull near the mastoid bones (just behind the ear). The authors suggested that these perforations were the result of two surgical procedures, one on each ear, by someone with rudimentary anatomical knowledge. There was more bone remodeling on the right ear, suggesting that the first surgery was done to treat a likely life-threatening condition, given the risks associated with such a procedure during this time.

The woman survived the first procedure and had a second surgery on the left ear some time after. The authors were unable to determine whether the procedures were performed back-to-back or whether they were months or even years apart. Anyway, “It is thus the earliest documented evidence of surgery on both temporal bones and therefore most likely the first known radical mastoidectomy in human history,” they wrote.

According to the authors, this was a fairly common surgical procedure in the 17th century to treat acute ear infections, and skulls showing signs of mastoidectomy have been found in Croatia (11th century), Italy (18th and 19th centuries) and Copenhagen (19th century). . or early 20th century). Perhaps the oldest form of skull surgery is cranial trepanation — drilling a hole in the head — that is well documented in the Iberian Peninsula. Five skulls recovered from a site close to the dolmens of El Pendón showed signs of trepanation, and the individuals apparently survived those procedures, despite the lack of antibiotics and a high risk of complications.

S. Diaz-Navarro et al., 2022

What condition could have led to such an intervention? The authors rule out a cholesteatoma — an injury to the temporal bone that can cause hearing loss, dizziness and other complications — although this is one of the best-documented diseases in pathological studies of ancient skulls. But cholesteatoma tends to erode the bony wall (scutum) separating the ear canal from the mastoid, and the scutum was intact on both sides of the woman’s skull. The authors also ruled out a bone tumor or malignant external otitis (a rapidly spreading infection of the ear canal and temporal bone).

The authors concluded that the most likely condition was acute middle ear infection, also called an inner ear infection, that had spread to the underlying bone, specifically the mastoid bone (mastoiditis). The condition would have been easy enough to diagnose as the infection causes visible swelling and redness as fluid and mucus build up in the ear. If an inner ear infection spread to the mastoid bone, the honeycomb-like structure of the bone would also be filled with fluid and mucus. Left untreated, this would have led to hearing loss and possibly meningitis. Mastoiditis due to an infection of the inner ear was one of the leading causes of death in children before antibiotics were widely available (and thankfully it’s a rare condition today).

A modern mastoidectomy involves removing the cells in the hollow, air-filled spaces of the mastoid bone. In a radical mastoidectomy, the surgeon first makes a cut behind the ear and then uses a bone drill to open access to the middle ear cavity. After that, the surgeon will remove any infected mastoid bone or tissue, stitch the cut, and bandage the wound. According to the authors, their late Neolithic ear surgeon would have followed a similar (albeit much cruder) procedure, removing the affected bone to drain the middle ear and then connecting the mastoid bone to the tympanic cavity surrounding the inner ear bone.