YouTube/University of Cambridge

One of many standout scenes in the 1975 classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail features King Arthur and his knights facing the Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog, a seemingly harmless rabbit who soon proves to be a devastating adversary, forcing the knights to retreat (“Run Away! Run Away!”). Killer rabbits are something of a mainstay of medieval literature, prominent in marginal illustrations, as well as a mention in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Stories. The Python crew even drew inspiration for their version from a scene on the facade of Notre Dame in Paris, in which a knight is on the run from a rabbit.

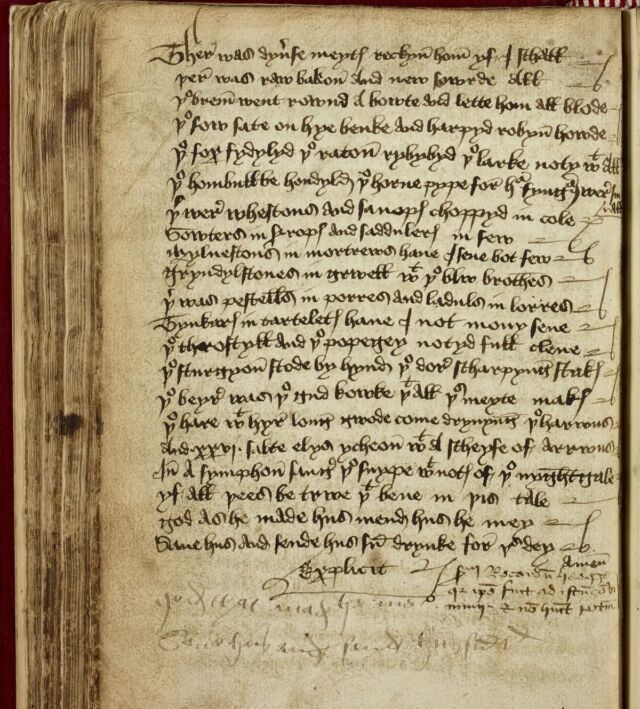

Killer rabbits may have even been a common trope among traveling minstrels, according to a scholar’s discovery of a written record of a live performance preserved in a 15th-century manuscript, which also contains one of the earliest recorded uses of the phrase “red herring” . James Wade of the University of Cambridge, author of a recent article published in The Review of English Studies, came across the manuscript while doing research at the National Library of Scotland.

The writer identified himself in the text as Richard Heege, a domestic clergyman and tutor to the Sherbrooke family in Derbyshire. Heege’s manuscript, with the addition of low-brow nonsense verse, a mock sermon and a burlesque romance, “gives us the rarest glimpse of a medieval world rich in oral storytelling and popular entertainment,” said Wade.

National Library of Scotland

Minstrels in the Middle Ages traveled from town to town and entertained people in noble halls, taverns and fairgrounds with their performances. Fictional minstrels are often mentioned in medieval literature, but according to Wade, it is rare to find a reference to an actual minstrel, and there are few if any written records of them. Most are records of payments to minstrels, listed by first name and instruments played.

While there are many medieval works with “oral” or “minstrel” tags, according to Wade, “No text has survived that we can confidently tie to any medieval minstrel, as a composer, proprietor, or performer.” Wade cautiously emphasizes that he’s not actually claiming to have discovered a manuscript written by a medieval minstrel. But he thinks the Heege manuscript was either a transcription of a minstrel’s live performance, or copied from a minstrel’s now-lost notes (a auxiliary memory). Among the evidence Wade cites is the note scrawled at the bottom of a page that reads, “By me, Richard Heege, because I was at that party and hadn’t been drinking”—implying that Heege was sober enough to talk about a to write minstrel. perform at that party.