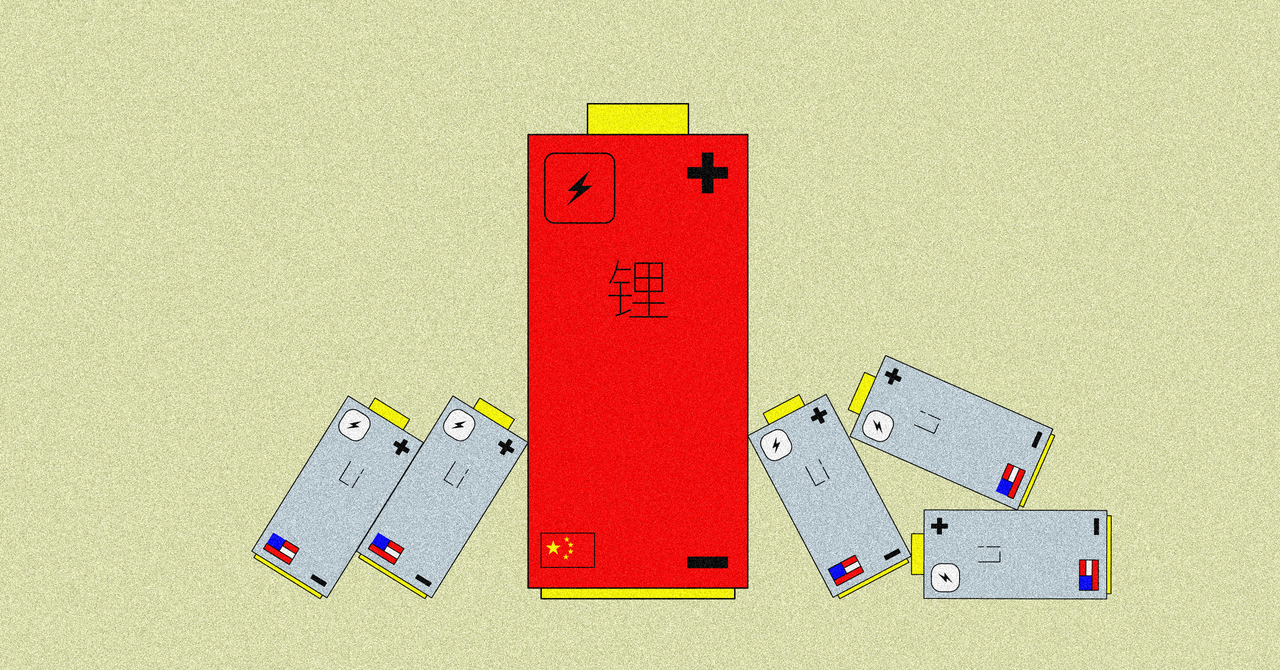

Lithium projects outside of China are at the mercy of the markets, slowing and expanding as the price of lithium ebbs and flows. But domestic investment has remained almost constant. As a result, China is the only country that can process lithium from raw material to finished batteries without relying on imported chemicals or components. This is mainly due to a political environment that emphasizes reducing the cost of lithium rather than maximizing shareholder value.

But China isn’t producing nearly enough lithium to satisfy its domestic hunger — and besides, only about 10 percent of the material that goes into a battery is actually lithium. The country is still dependent on imports of cobalt, nickel, copper and graphite, which for the time being ensures a certain mutual cooperation. “It’s really an intertwined system,” said Lukasz Bednarski, battery materials analyst and author of Lithium: The Global Race for Battery Dominance and the New Energy Revolution† “The western world and China are kind of codependent.”

Neither side is interested in starting a trade war, which has led to a somewhat uneasy standoff, Barron says. “If China decides not to export batteries for electric vehicles, countries in the West may decide not to export the nickel to China,” he says. “China doesn’t have the refineries to produce the highest purity nickel.”

The balance of power can shift if both sides invest in energy independence. As the West rushes to build mines and factories, China is beginning to exploit untapped lithium resources in Xinjiang and the salt lakes of the Tibetan Plateau. That can come with a human price: a report by The New York Times found evidence of forced labor at mining operations in Xinjiang, which could be a potential flashpoint if sanctions protecting the Uyghur minority prevented Western companies from importing chemicals mined in that region.

Ultimately, lithium is not fundamentally scarce. As prices rise, new technologies may become more economically viable — a way to extract lithium from seawater, for example, or an entirely new type of battery chemistry that eliminates the need for lithium altogether. However, in the short term, supply shortages could disrupt the move to electric cars. “There can be hiccups — years when the price of raw material skyrockets and there are temporary shortages in the market,” Bednarski says.

Chinese automakers will have a huge advantage if that happens. Chinese brands like Nio and Chinese brands like MG are already launching electric vehicles in the West which are the cheapest on the market. “Western Chinese-owned companies will have a huge advantage over their European or American competitors,” Barron said.

Once operational, the lithium plant in Kwinana will ship 24,000 tons of Australian lithium hydroxide per year. But that lithium, which is mined in Australia for batteries built in South Korea and Sweden and destined for electric vehicles sold in Europe and the US, relies on China every step of its journey. The shell of the old oil refinery still stands as a monument to the centuries-long battle over fossil fuels that reshaped the world, but a new race is underway – and China is at the wheel.