B612 Asteroid Institute | University of Washington DiRAC Institute | DECam

Giant asteroids have hit Earth before – RIP dinosaurs – and if we’re not careful about all those wandering space rocks, they could crash into our world again, with devastating consequences. That’s why Ed Lu and Danica Remy of the Asteroid Institute have started a new project to follow as many of them as possible.

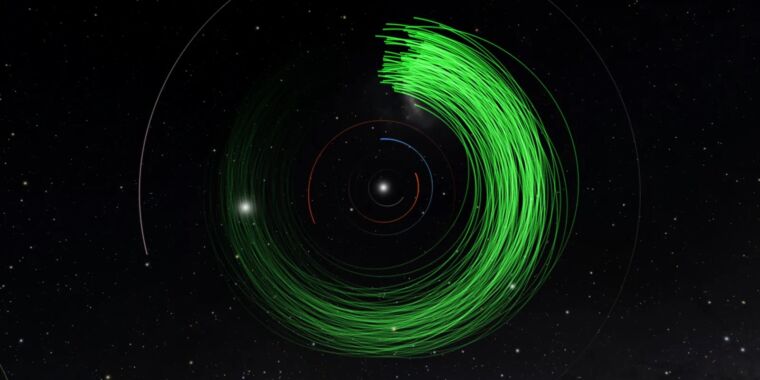

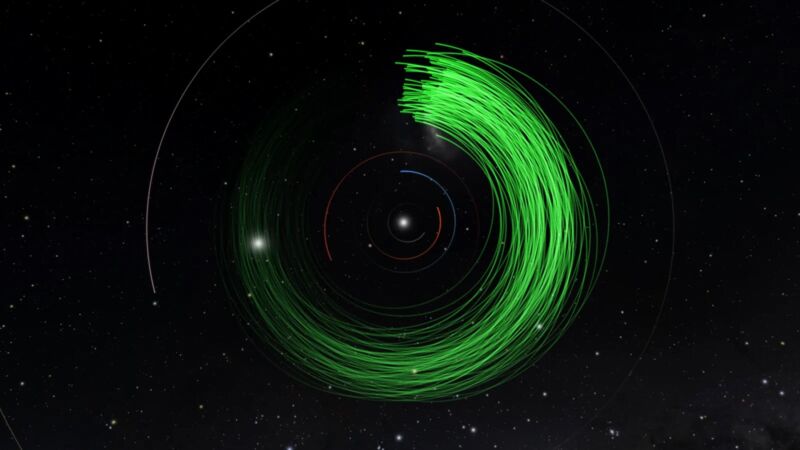

Lu, a former NASA astronaut and executive director of the institute, led a team that developed a new algorithm called THOR that uses massive computing power to compare points of light seen in different images of the night sky, then combines them. to determine the path of an individual asteroid through the solar system. They have already discovered 104 asteroids with the system, according to an announcement they released Tuesday.

While NASA, the European Space Agency and other organizations have their own ongoing asteroid searches, they all face the challenge of analyzing telescope images of thousands or even 100,000 asteroids. Some of those telescopes may or may not be able to take multiple photos of the same region on the same night, making it difficult to tell whether the same asteroid appears in multiple photos taken at different times. But THOR can make the connection between them.

“The magic of THOR is that it realizes that of all those asteroids, this one in one image, and this one in another image four nights later, and these seven nights later, are all the same object and can be put together like the orbit of a real asteroid,” says Lu. This makes it possible to track the object’s path as it moves, and determine whether it is on orbit to Earth. Such a formidable task would not have been possible with older, slower computers, he adds. “This demonstrates the importance of calculations for moving forward in astronomy. What’s driving this is that calculations are becoming so powerful and so cheap and ubiquitous.”

Astronomers usually spy on asteroids with something called a “tracklet,” a vector measured from multiple images, usually taken within an hour. Often it involves a sighting pattern with six or more images, which allows researchers to reconstruct the asteroid’s route. But if the data is incomplete, for example because a cloudy night obscures the telescope’s view, that asteroid will remain unconfirmed, or at the very least untraceable. But that’s where THOR, which stands for Tracklet-less Heliocentric Orbit Recovery, comes in, making it possible to pinpoint the path of an asteroid that would have otherwise been missed.

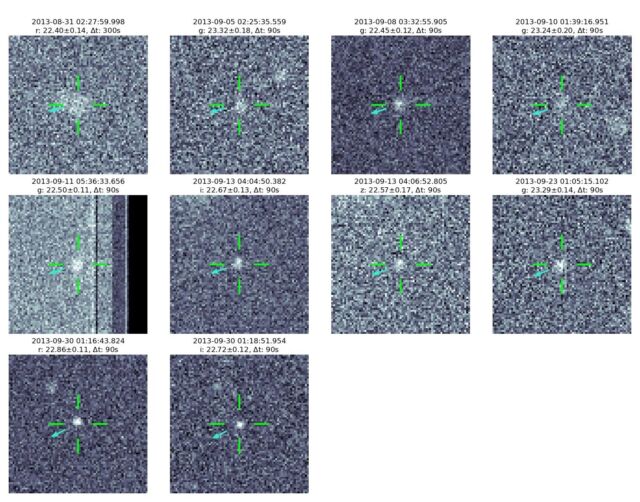

While NASA takes advantage of telescopes and studies aimed at spotting potentially dangerous asteroids, there are plenty of other datasets out there. And THOR can use almost all of them. “THOR turns any astronomical dataset into a dataset in which you can search for asteroids. That’s one of the coolest things about the algorithm,” said Joachim Moeyens, co-creator of THOR, and an Asteroid Institute fellow and graduate student at the University of Washington. For this first demonstration, Moeyens, Lu and their colleagues searched billions of images taken between 2012 and 2019 with telescopes operated by the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, many by a sensitive camera mounted on the Blanco 4-meter telescope in the Chilean Andes.

B612 Asteroid Institute | University of Washington DiRAC Institute | DECam