When satellites first began peering into the rugged, glacier-covered Antarctic Peninsula about 40 years ago, they saw only a few small patches of vegetation totaling about 8,000 square meters – less than a football field.

But since then, the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed rapidly, and a new study shows that mosses, along with some lichens, liverworts and associated algae, have colonized more than 7.5 square kilometers, an area almost four times the size of the Central Park in New York.

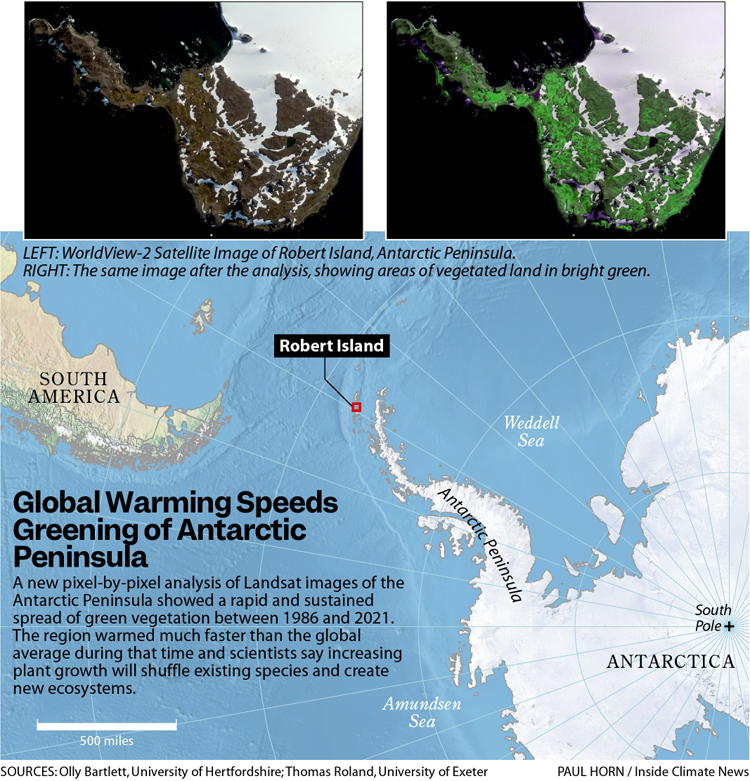

The findings, published Friday in Nature Geoscience, based on a meticulous analysis of Landsat images from 1986 to 2021, show that the greening trend is distinct from natural variability and has accelerated by 30 percent since 2016, fast enough to reach almost 75 cover football matches. fields per year.

Greening on the other side of the planet, in the Arctic, has been extensively studied and reported, said co-author Thomas Roland, a paleoecologist at the University of Exeter who collects and analyzes mud samples to study ecological and ecological changes. “But the idea,” he said, “that any part of Antarctica could be green in any way is something that still confuses many people.”

Credit: Inside Climate News

Credit: Inside Climate News

As the planet warms, “even the coldest areas on Earth, which we expect and understand to be white and black with snow, ice and rocks, are starting to turn greener as the planet responds to climate change,” he said.

The tenfold increase in vegetation cover since 1986 “is not huge in the global scheme of things,” Roland added, but the accelerating pace of change and the potential ecological impacts are significant. “That's the real story here,” he said. “The landscape will change partly because the existing vegetation is expanding, but it may also change in the future if new vegetation is added.”