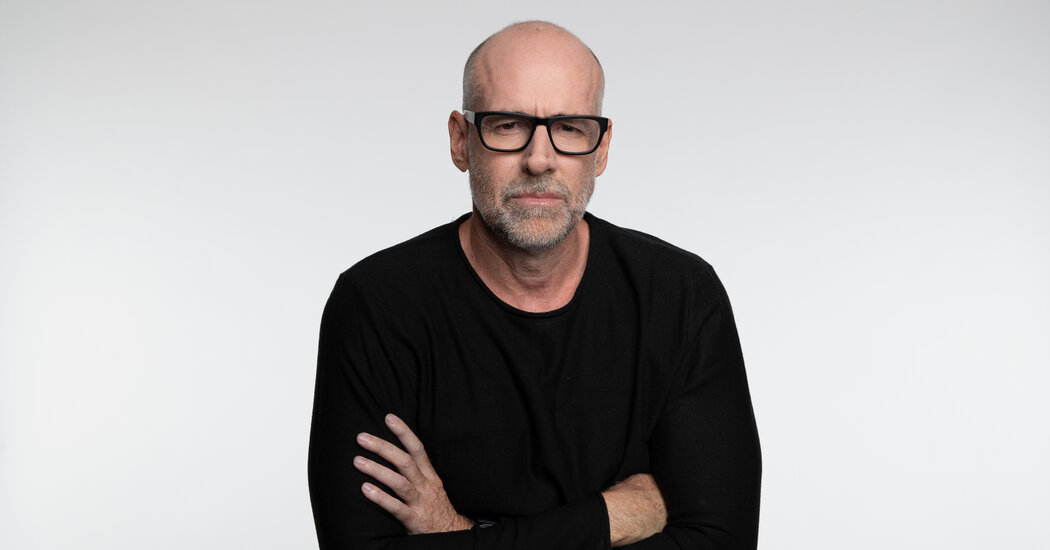

Early on in the pandemic, he began writing a book on crises from 1945 to the present to explain the momentous changes in our society and economy. Prior to the fall release of the book “Adrift: America in 100 Charts,” DealBook spoke with Mr. Galloway about what he discovered during his research about America and where he thinks we are headed.

The conversation has been edited and shortened for clarity and length.

Your book suggests that the depths of the recession could be a great time to start a startup. With all the warning bells from markets and the Fed, should people think entrepreneurially?

What the evidence shows is that it’s actually a really good time to start a business. When you start a business in a recession, it’s cheaper – everything from real estate to employees to technology is less expensive. It sounds counterintuitive, but building a business during a recession puts the quality of the business to the test early on. It’s like when you want soldiers who’ve been through combat – a business that starts out in a recession, and if it survives a recession, it kind of tests a battle to see if it’s a viable business. Then you have the wind of recovery at your back.

And when they come out of a recession, businesses and consumers re-evaluate their purchases and are much more open to new ideas and new suppliers.

Speaking of a recession, what do you think Silicon Valley will look like on the other side?

What you have in a bull market, like we’ve had for the past 13 years, is that the market responded positively to growth and as long as you could increase your sales at a steady clip, the market, basically Netflix and Amazon, said we liked this and continued to increase the value of the company.

Now a few things happened: If companies like Uber look like it’s hard to imagine they’ll ever be profitable with a sustainable business — even with growth, and they’ve grown, it’s still so far from being profitable — the market does not.

Twitter has actually lost more money in its history than it has made. And with rising interest rates, borrowing costs — businesses that are losing money or aren’t profitable yet — are rising because you have to borrow money at much higher rates. In addition, the profits you expected in the future are discounted at a much higher rate. In some growth companies, it costs more to fund what will ultimately be worthless cash flows. Their equity is absolutely hammered here and now.

What do you advise those companies to do?

There is no magic wand. It is cost saving. They will have to cut costs and, in some cases, adopt a business model so that they can achieve higher prices and drastically lower costs. And frankly, convincing the market that they can become profitable faster because the costs of financing that runway to profitability have become much greater. So they have to show that the distance, the runway needed to become profitable, is shorter. They basically have to trade growth for a shortcut to profitability. That’s what the market tells them.

In your book you look at how, during every economic upturn, there is optimism that we are going to solve inequality. But we always seem to fall short. Why?

We confuse prosperity with progress. And we have created tremendous, staggering, unprecedented prosperity. I think the mistake or the myth we believe in – that when there is economic prosperity, GDP grows, that will translate into progress for a nation.

What do we mean by progress? I think the ballast — and it’s my first chapter in the book — is a healthy and thriving middle class. A nation’s geopolitical power, its well-being, its democratic strength, usually depends on how prosperous the middle class is.

The problem in America – and Europe makes it to a lesser extent – is that America has either believed this myth that the middle class is a natural object of a free market economy, and it isn’t. The middle class is an accident. It’s an aberration of economics.

There is a constant notion that if the economy does well, the middle class will recover itself. That is not true. What happens over time in all of economic history is that the rich arm the government, lower taxes on them, resist competition — the biggest, most powerful corporations hole up, and you end up with a hollowing out of the middle class. You end up with income inequality. It gets worse and worse, and then the same thing happens with income inequality. The good news is that when income inequality reaches these levels, it always corrects itself. The bad news is that the mechanisms of self-correction are war, famine and revolution.

Unless you provide and invest in a strong middle class, be it minimum wage or support unions or vocational training or access to free education or low cost education, the middle class disappears as an entity. We’ve fallen for the idea that as long as the economy is doing well, the middle class will do well. The two are not necessarily linked.

You warned early on about too many pandemic-era stimulus measures having a bad impact on the economy. What should we have done differently?

We spent a minimum of $7 trillion – but it was nothing but cloud cover where we threw some loaves of bread and games to the poor so we could boost the economy tremendously. Most of the money went into the market, and who owns 90 percent of real estate shares by dollar volume? The top 1 percent. The PPP, the small business bailout, was nothing but a giveaway for the rich. The richest cohort in America is, just wait, the small business owners. The millionaire next door has a car wash.

This is Covid’s dirty secret. If you’re in the top 10 percent, you’re living your best life. For you, Covid meant more time with family, more time with Netflix — and you saw your inventory accelerate.

If you flush $7 trillion into the economy and couple that with war and supply chain bursts, now it seems clear: we have too many dollars chasing too few products. And of course, the people who will be most affected by inflation are the people who don’t have pillows. We definitely overdid it.

You’ve been skeptical about crypto for a long time, and now we’re seeing a real crash. What do you think will happen now?

What we found is this whole mantra of a reliable economy, we should not have trusted many of these new actors.

Even in ’99, there were many use cases of the Internet – you could buy CDs and books on Amazon. You can get real-time news on Yahoo. It is more difficult to find use cases of the blockchain that affect the everyday consumer. I think you’re just seeing a massive unfolding or space delivery — and I think we’re in the midst of a crash that will probably be unprecedented in terms of an asset class.

If you look at the bubble – if you compare it to previous bubbles, be it tulips, ’99 internet stocks, houses, Japanese stocks – the run-up here has been extraordinary. The run-up here makes the others look sheepish or modest, meaning the crash will be equally or more violent.

More lawsuits to come. There will be more calls for additional regulations. You’ll see investors say, where were the regulators?

That’s the bad news. The good news is that it probably won’t have much of an impact on the real economy. Keep in mind that even if all cryptocurrencies went to zero right now, that would still be less than half of Apple’s value.

What do you think? Do you agree with Mr Galloway’s predictions? Let us know: dealbook@CBNewz.