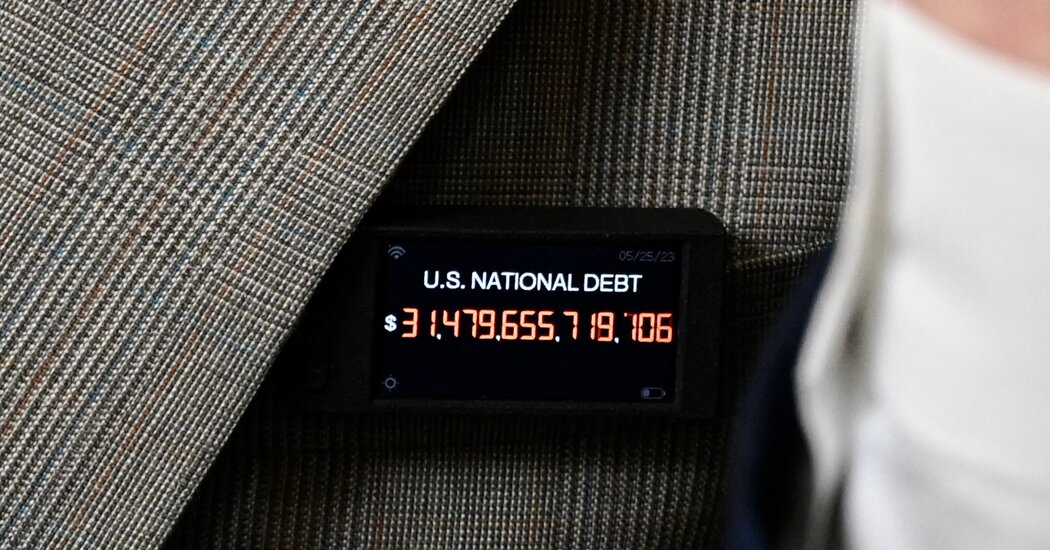

The bipartisan agreement to avert government bankruptcy this week included modest cuts to a relatively small portion of the federal budget. As a drag on US debt growth of $31.4 trillion, it was a minor breakthrough at best.

It also showed how difficult — if not impossible — it could be for lawmakers to agree on a major breakthrough in the near term to demonstrably reduce the country’s debt burden.

There is no clear economic evidence that the current level of debt is affecting economic growth. Some economists argue that rising debt levels will hurt growth by making it more difficult for companies to borrow money; others say that rising future costs of government borrowing could cause rapid inflation.

But Washington is again pretending to be concerned about debt, which will reach $50 trillion by the end of the decade, even after factoring in recent spending cuts.

With that pretext comes the reality that the fundamental drivers of American politics all point to the United States borrowing more, not less.

The bipartisan agreement to suspend the debt ceiling for two years, passed by the Senate on Thursday, effectively sets the overall discretionary spending level for that period. The agreement cuts federal spending by $1.5 trillion over a decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office, by essentially freezing some of the funding expected to rise next year and then limiting spending to 1 percent growth in 2025.

But even with those cuts, the deal provides clear evidence that the country’s overall debt burden isn’t going down any time soon.

Republicans cited rising debt as a reason to refuse to raise the limit, risking default and a financial crisis unless Biden agreed to measures to reduce future deficits. But White House negotiators and the House Republican leadership could only agree on big savings from nondefensive discretionary spending.

That’s the portion of the budget that funds Pell grants, federal law enforcement, and a wide variety of domestic programs. As a share of the economy, it is well within historical levels and is expected to fall in the coming years. Currently, basic discretionary spending accounts for less than one-eighth of the $6.3 trillion the government spends annually.

The deal did not include major cuts in military spending, which exceed basic non-defense discretionary spending. Early in the talks, both sides ruled out changes to the two biggest drivers of federal spending growth over the next decade: Social Security and Medicare. The cost of those programs is expected to skyrocket within 10 years as retired baby boomers become eligible for benefits.

While Republicans initially hesitated when Mr. Biden accused them of wanting to cut those politically popular programs, they quickly moved to blaming the president for taking them off the table.

Asked on Fox News on Wednesday why Republicans hadn’t cut the entire budget, speaker Kevin McCarthy replied, “Because the president has walled off everyone else.”

“The main driver of the budget is compulsory spending,” he said. “It’s Medicare, Social Security, interest on the debt.”

Negotiators for Mr. McCarthy have effectively walled off the other half of the debt equation: revenue. They rejected Mr Biden’s pitch to raise trillions of dollars from new taxes for corporations and high earners, and both sides eventually agreed to cut funding for the Internal Revenue Service, which was expected to bring in more money by targeting tax fraud. to take.

Instead, Republicans tried to view the rising national debt as solely a spending problem, not a tax revenue problem, even as tax cuts by both sides have added trillions to the debt since the turn of the century.

Republican leaders now appear poised to introduce another round of tax cut proposals, likely to be financed with borrowed money, a move Democrats denounced during the floor debate over the debt ceiling agreement.

“Before the ink dries on this bill, you will be pushing for $3.5 trillion in corporate tax cuts,” Wisconsin Democrat Representative Gwen Moore said shortly before the final vote on the Fiscal Responsibility Act, as it is called, on Wednesday. .

Those comments echoed a lesson Democrats learned from 2011, when Washington’s leaders last made a big show by pretending to care about debt in a bipartisan deal to raise the borrowing limit. That agreement, between President Barack Obama and President John Boehner, limited discretionary spending growth for a decade, pushing budget deficits down for years.

Many Democrats now believe that those lower deficits gave Republicans the fiscal and political space they needed to pass a 2017 tax cut package under President Donald J. Trump that the Congressional Budget Office estimates would add nearly $2 trillion to the national debt. They’ve come to believe that Republicans would be happy to do the same thing again with future budget deals — putting aside concerns about deficits and effectively turning budget cuts into new tax breaks.

At the same time, both parties have become wary of cuts in Social Security and Medicare. Mr. Obama was willing to reduce the future growth of pension benefits by changing the way they were linked to inflation; Mr. Biden is not. Mr. Trump won the White House after promising to protect both programs, in a lull from past Republicans, and is currently tossing his rivals over potential program cuts as he seeks the presidency again.

In all that time, the total amount of federal debt has more than doubled to $31.4 trillion from just under $15 trillion in 2011. That growth has had no discernible effect on the economy’s performance. But it is expected to continue to grow over the next decade as the retired baby boomers receive more government benefits. The budget bureau estimated last month that public debt would be nearly 20 percent larger, as a share of the economy, by 2033 than it is today.

Even under a generous score from the new agreement, which assumes Congress will effectively commit two years of spending cuts over the course of a decade, that growth will only decline by a few percentage points.

Debt reduction groups in Washington have celebrated the deal as a first step toward a greater compromise to reduce America’s dependence on borrowed money. But neither Mr. McCarthy nor Mr. Biden have shown any interest in what those groups want: a mix of significant pension program cuts and increases in tax revenue.

Mr McCarthy suggested this week that he would soon form a bipartisan committee to sift through the entire federal budget “so we can find the waste and we can make the real decisions to really take care of this debt.”

The 2011 debt deal produced a similar commission, which made recommendations on politically painful steps to reduce the debt. Lawmakers have thrown them out. There is no evidence that they would do anything differently today.