To combat misinformation, California lawmakers are introducing a bill that would compel social media companies to disclose their process for removing false, hateful or extremist material from their platforms. Texas lawmakers, on the other hand, want to ban the largest of the companies — Facebook, Twitter and YouTube — from deleting posts for political stances.

In Washington, the state attorney general persuaded a court to fine a nonprofit and its attorney $28,000 for filing an unfounded legal challenge to the 2020 governor’s race in Alabama lawmakers want to allow people to claim financial damages from social media platforms that shut down their accounts for posting fake content.

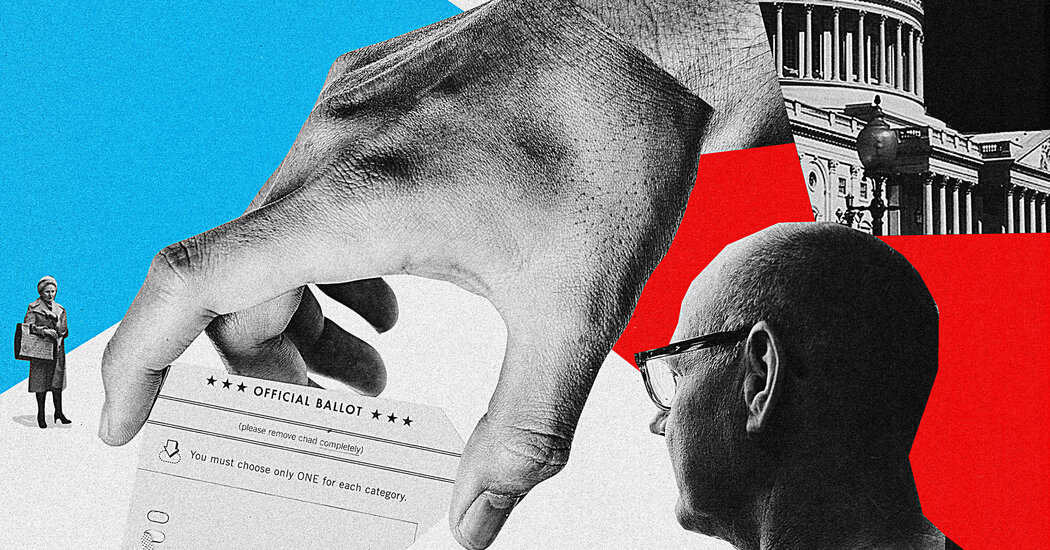

In the absence of significant action against disinformation at the federal level, state after state officials are targeting the sources of disinformation and the platforms that spread it—only they do so from widely differing ideological points of view. In this deeply polarized era, even the struggle for truth breaks down partisan lines.

The result is a cacophony of state laws and legal maneuvers that could amplify information bubbles in a nation increasingly divided on a variety of issues — including abortion, weapons, the environment — and along geographic lines.

The midterm elections in November provide much of the activity at the state level. In red states, the emphasis has been on protecting conservative voices on social media, including those spreading baseless claims of widespread election fraud.

In blue states, lawmakers have tried to force the same companies to do more to stop the spread of conspiracy theories and other harmful information on a wide variety of topics, including voting rights and Covid-19.

“We should not stand by and raise our hands and say that this is an impossible beast that is going to take over our democracy,” Washington Governor Jay Inslee, a Democrat, said in an interview.

He calls disinformation a “nuclear weapon” that threatens the country’s democratic foundations, and he supports legislation that would make it a crime to spread electoral lies. He praised the $28,000 fine imposed on the advocacy group that denounced the integrity of the 2020 state vote.

“We should be creatively looking for possible ways to mitigate its impact,” he said, citing misinformation.

The biggest hurdle to new regulations — regardless of the party pushing them — is the First Amendment. Lobbyists for the social media companies say that while they try to moderate the content, the government should not dictate how it should be done.

Freedom of speech concerns defeated a bill in deep blue Washington that would have made it a crime, with a jail term of up to one year, for candidates or elected officials “to spread lies about free and fair elections when has the potential to foment violence.”

Governor Inslee, who faced unfounded claims of voter fraud after winning a third term in 2020, supported the legislation, citing the 1969 Supreme Court ruling in Brandenburg v. Ohio. That ruling allowed states to punish expressions that incite violence or criminal acts when “such advocacy is aimed at instigating or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite such action.”

The legislation stalled in the state Senate in February, but Mr Inslee said the magnitude of the problem required urgent action.

The scale of the problem of disinformation and of the power of the tech companies is beginning to dwindle from the idea that free speech is politically untouchable.

The new Texas law has already reached the Supreme Court, which blocked the law’s entry into force in May, though it sent the case back to a federal appeals court for further consideration. Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, signed the legislation last year, prompted in part by Facebook and Twitter decisions to shut down former President Donald J. Trump’s accounts after the violence on Capitol Hill on Jan. 6, 2021.

The court’s ruling indicated that it could rethink one core issue: whether social media platforms, such as newspapers, retain a high degree of editorial freedom.

“It’s not at all clear how our existing precedents, which predate the Internet age, should apply to major social media companies,” Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote. in a dissent with the court’s emergency ruling suspending enforcement of the law.

A federal judge last month blocked a similar Florida law that would have fined social media companies as much as $250,000 a day for blocking political candidates from their platforms, which have become essential tools of modern campaigning. Other states with Republican-controlled legislatures have proposed similar measures, including Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and Alaska.

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall has created an online portal where residents can complain that their social media access has been restricted: alabamaaag.gov/Censored. In a written response to questions, he said social media platforms have stepped up their efforts to restrict content during the pandemic and the 2020 presidential election.

“During this period (and to this day), social media platforms have given up all pretensions to promote freedom of expression – a principle by which they sold themselves to users – and openly and arrogantly proclaimed themselves the Ministry of Truth,” he wrote. “Suddenly any point of view that deviated in the least bit from the prevailing orthodoxy was censored.”

Much of the activity at the state level today is motivated by the fraudulent claim that Mr. Trump, not President Biden, won the 2020 presidential election. Though repeatedly refuted, the claim has been cited by Republicans to introduce dozens of bills that would counteract absentee voting or incoming votes in the states they control.

Democrats have gone in the opposite direction. Sixteen states have expanded people’s options to vote, reinforcing preemptive accusations among conservative lawmakers and commentators that Democrats are out to cheat.

“There is a direct line from conspiracy theories to lawsuits to legislation in states,” said Sean Morales-Doyle, acting director of voting rights at the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan election advocacy organization at New York University School of Law. “Now more than ever, your right to vote depends on where you live. What we’ve seen this year is half the country going one way and the other half going the other way.”

TechNet, the lobbying group of internet companies, has fought local proposals in dozens of states. Industry executives argue that variations in state law create a confusing patchwork of rules for businesses and consumers. Instead, companies have emphasized their own enforcement of misinformation and other malicious content.

“These decisions are made as consistently as possible,” said David Edmonson, the group’s vice president for state policy and government relations.

For many politicians, the issue has become a powerful bludgeon against opponents, with each side accusing the other of spreading lies, and both groups criticizing the social media behemoths.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, has raised campaign money on his vow to continue his fight against what he called the “authoritarian corporations” seeking to mute conservative votes.

In Ohio, JD Vance, the memoirist and Republican Senate nominee, scolded social media giants and said they were suppressing news of the foreign business dealings of Hunter Biden, the president’s son.

In Missouri, Vicky Hartzler, a former congressman running for the Republican Senate nomination, ran a television ad criticizing Twitter for suspending her personal account after she made comments about transgender athletes. “They want to cancel you,” she said in the ad, defending her comments as “what God intended.”

OnMessage, a polling agency that considers the National Republican Senatorial Committee a client, reported that 80 percent of primary voters surveyed in 2021 said they believed tech companies were too powerful and should be held accountable. Six years earlier, only 20 percent said that.

“Voters have a palpable fear of the cancellation culture and how technology censors political views.” said Chris Hartline, a spokesman for the National Republican Senatorial Commission.

In blue states, Democrats have focused more directly on the harm disinformation does to society, including through false claims about elections or Covid and through racist or anti-Semitic material that has led to violent attacks, such as the Buffalo supermarket massacre in May.

Connecticut, plans to spend nearly $2 million on marketing to share factual information about votes and position an expert to stamp out misinformation about votes before they go viral. A similar attempt to create a disinformation board at the Department of Homeland Security sparked political anger before operations were suspended in May pending an internal review.

In California, the state Senate is moving forward with legislation requiring social media companies to disclose their policies regarding hate speech, disinformation, extremism, harassment and foreign political interference. (The legislation wouldn’t force them to restrict content.) Another bill would allow civil lawsuits against major social media platforms like TikTok and Meta’s Facebook and Instagram if their products were proven to have addicted children.

“All of these different challenges that we face have a common thread, and the common thread is the power of social media to amplify really problematic content,” said California councilor Jesse Gabriel, a Democrat, who sponsored the legislation to increase transparency. of social media platforms. “That has major consequences, both online and in physical spaces.”

The flurry of legislative activity seems unlikely to have a significant impact ahead of this fall’s election; social media companies will not have a single, mutually acceptable response when allegations of disinformation inevitably arise.

“Each election cycle brings intense new content challenges for platforms, but the November midterms look likely to be particularly explosive,” said Matt Perault, director of the Center on Technology Policy at the University of North Carolina. “With abortion, guns and democratic participation at the forefront of voters, platforms will face intense challenges in moderating speech. It’s likely neither side will be happy with the decisions platforms make.”