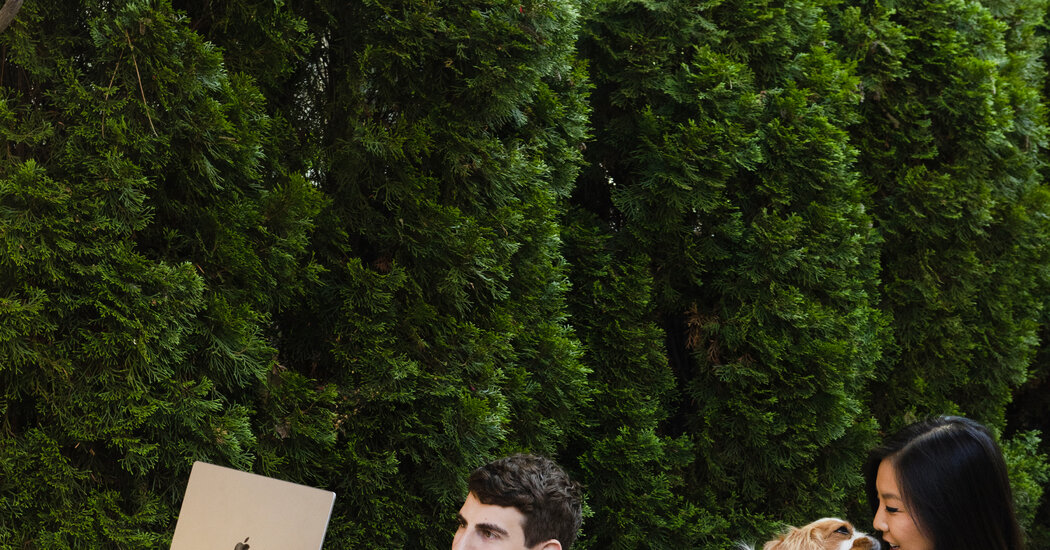

The life of Doug Fulop and Jessie Fischer in Bend, Oregon, was idyllic. The couple moved there last year and worked remotely in a 2,400-square-foot home surrounded by trees, with easy access to skiing, mountain biking, and breweries. It was an upgrade from their former apartments in San Francisco, where a stranger once entered Mr. Fulop’s house after his lock didn’t close properly.

But the pair of tech entrepreneurs are now heading back to the Bay Area, driven by a major development: the rise of artificial intelligence.

Mr. Fulop and Ms. Fischer are both start-ups using AI technology and are seeking co-founders. They tried to make it work in Bend, but after too many eight hours of driving to San Francisco for hackathons, networking events, and meetings, they decided to move back when their lease expires in August.

“The AI boom has brought back the energy to the bay that was lost during Covid,” said 34-year-old Mr Fulop.

The pair are part of a growing group of boomerang entrepreneurs who see opportunity in San Francisco’s predicted demise. The tech industry has been in its worst slump in a decade for more than a year, with layoffs and a plethora of empty offices. The pandemic also sparked a wave of migration to places with lower taxes, fewer Covid restrictions, safer streets and more space. And tech workers were among the most vociferous groups to criticize the city for its growing drug, housing and crime problems.

But such failures are almost always followed by a new boom. And with the latest wave of AI technology – known as generative AI, which produces text, images and video in response to prompts – the stakes are too much to miss.

Investors have already announced $10.7 billion in funding for generative AI startups in the first three months of this year, a 13-fold increase from a year earlier, according to PitchBook, which tracks startups. Tens of thousands of tech workers recently laid off by big tech companies are now eager to join the next big thing. In addition, much of the AI technology is open source, meaning companies share their work and allow anyone to build on it, fostering a sense of community.

San Francisco’s Hayes Valley neighborhood, known as “Cerebral Valley,” is where “hacker houses,” where people set up start-ups, are springing up because it’s the center of the AI scene. And every evening someone organizes a hackathon, meet-up or demo focused on the technology.

In March, days after prominent start-up OpenAI unveiled a new version of its AI technology, an “emergency hackathon” organized by a few entrepreneurs drew 200 participants, with nearly as many on the waiting list. That same month, a networking event hurriedly organized via Twitter by Clement Delangue, the CEO of the AI start-up Hugging Face, drew more than 5,000 people and two alpacas to the Exploratorium museum in San Francisco, earning it the nickname “Woodstock of AI” yielded.

Madisen Taylor, who runs operations for Hugging Face and co-hosted the event with Mr. Delangue, said the community atmosphere mirrored that of Woodstock. “Peace, love, build cool AI,” she said.

All things considered, the activity is enough to attract people like Ms. Fischer, who is starting a business that uses AI in the hospitality industry. She and Mr. Fulop got involved in the 350-strong tech scene in Bend, but they missed the inspiration, bustle, and connections in San Francisco.

“There’s just nowhere else like the bay,” said 32-year-old Ms Fischer.

Jen Yip, who has hosted events for tech workers for the past six years, said what had been a quiet tech scene in San Francisco during the pandemic started to change last year along with the AI boom. During nightly hackathons and demo days, she saw people meeting their co-founders, raising investments, winning over clients and networking with potential employees.

“I’ve seen people come to an event with an idea they want to test and pitch it to 30 different people over the course of one night,” she said.

Ms. Yip, 42, leads a secret group of 800 people focused on AI and robotics called the Society of Artificers. The monthly events have become a hot ticket, often selling out in under an hour. “People are definitely trying to crash,” she said.

Her other speaker series, Founders You Should Know, features AI company leaders speaking to an audience of mostly engineers looking for their next gig. The last event had more than 2,000 applicants for 120 seats, Ms. Yip said.

Bernardo Aceituno moved his company, Stack AI, to San Francisco in January to become part of the start-up accelerator Y Combinator. He and his co-founders planned to establish the company in New York after the three-month program ended, but decided to stay in San Francisco. The community of fellow entrepreneurs, investors and tech talent they found was too valuable, he said.

“If we move, it will be very difficult to recreate in another city,” said 27-year-old Aceituno. “Whatever you’re looking for, it’s already here.”

After working remotely for several years, Y Combinator has begun encouraging startups in its program to move to San Francisco. Of a recent group of 270 startups, 86 percent participated locally, the company said.

“Hayes Valley really has become Cerebral Valley this year,” said Gary Tan, general manager of Y Combinator, during a demo day in April.

The AI boom is also luring back founders of other types of technology companies. Brex, a financial technology start-up, declared itself “remote first” early in the pandemic and closed its 250-person office in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood. The founders of the company, Henrique Dubugras and Pedro Franceschi, left for Los Angeles.

But as generative AI took off last year, Mr Dubugras, 27, was eager to see how Brex could apply the technology. He quickly realized he missed the coffee, casual conversations and community happening around AI in San Francisco, he said.

In May, Mr. Dubugras to Palo Alto, California, and began working out of a new, slimmed-down office a few blocks from Brex’s old one. High office vacancy rates in San Francisco left the company paying a quarter of what it paid in rent before the pandemic.

Seated under a neon sign in Brex’s office that reads “Growth Mindset,” Mr. Dubugras that since his return he had a regular schedule of coffee meetings with people working on AI. He has a Stanford Ph.D. student to tutor him on the subject.

“Knowledge is concentrated at the edge of the blood,” he said.

Mr. Fulop and Mrs. Fischer said they would miss their life in Bend, where they could ski or mountain bike during their lunch breaks. But getting two startups off the ground requires an intense mix of urgency and focus.

In the Bay Area, Ms. Fischer attends multi-day events where people stay up all night working on their projects. And Mr. Fulop runs into engineers and investors he knows every time he walks past a coffee shop. They are considering living in suburbs like Palo Alto and Woodside in addition to San Francisco, where nature is within easy reach.

“I’m willing to sacrifice the amazing tranquility of this place because I’m close to that aspiration, inspired, knowing there are a lot of great people to work with that I can come across,” Mr Fulop said. Living in Bend, he added, “just honestly felt like early retirement.”