BROWNSVILLE, Texas (AP) — Shelters in a Texas town struggled Saturday to find space for migrants who authorities say have started abruptly in their thousands from Mexico, testing a stretch of the U.S. border typically equipped to large groups of people fleeing poverty and violence.

The pace of arrivals in Brownsville seemed to overwhelm the town at the southernmost tip of Texas, stretching Social Services and placing a night shelter in an unusual position to turn people away. Officials say more than 15,000 migrants, mostly from Venezuela, have illegally crossed the river near Brownsville since last week.

That’s a sharp increase from the 1,700 migrants Border Patrol agents encountered in the first two weeks of April, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials.

“It’s quite concerning because the logistical challenge we’re facing is huge for us,” said Gloria Chavez, chief of the US Border Patrol Rio Grande Valley Sector.

The reason for the increase was not immediately clear. Chavez said migrants have been frustrated by relying on a glitch-ridden government app that allows them to apply for asylum at a port of entry. Some migrants crossing the border this week cited other drivers, including cartel threats that immediately preceded the sudden increase.

The uptick comes as the Biden administration plans to end pandemic-era asylum restrictions. US authorities have said daily illegal crossings from Mexico could reach 13,000, up from about 5,200 in March.

Other cities – some far from the southern border with the US – are also grappling with a sudden large influx of migrants. In Chicago, authorities this week reported a tenfold increase in migrant arrivals in the city, where as many as 100 migrants are beginning to arrive daily and start hiding in police stations.

Brownsville is just across the Rio Grande from Matamoros, Mexico, where a sprawling encampment of makeshift tents has housed about 2,000 people waiting to enter the U.S.

Last week some tents were set on fire and destroyed. Some migrants have said cartel-backed gangs were responsible, but a government official suggested the fires could have been started by a group of migrants frustrated with their long waits.

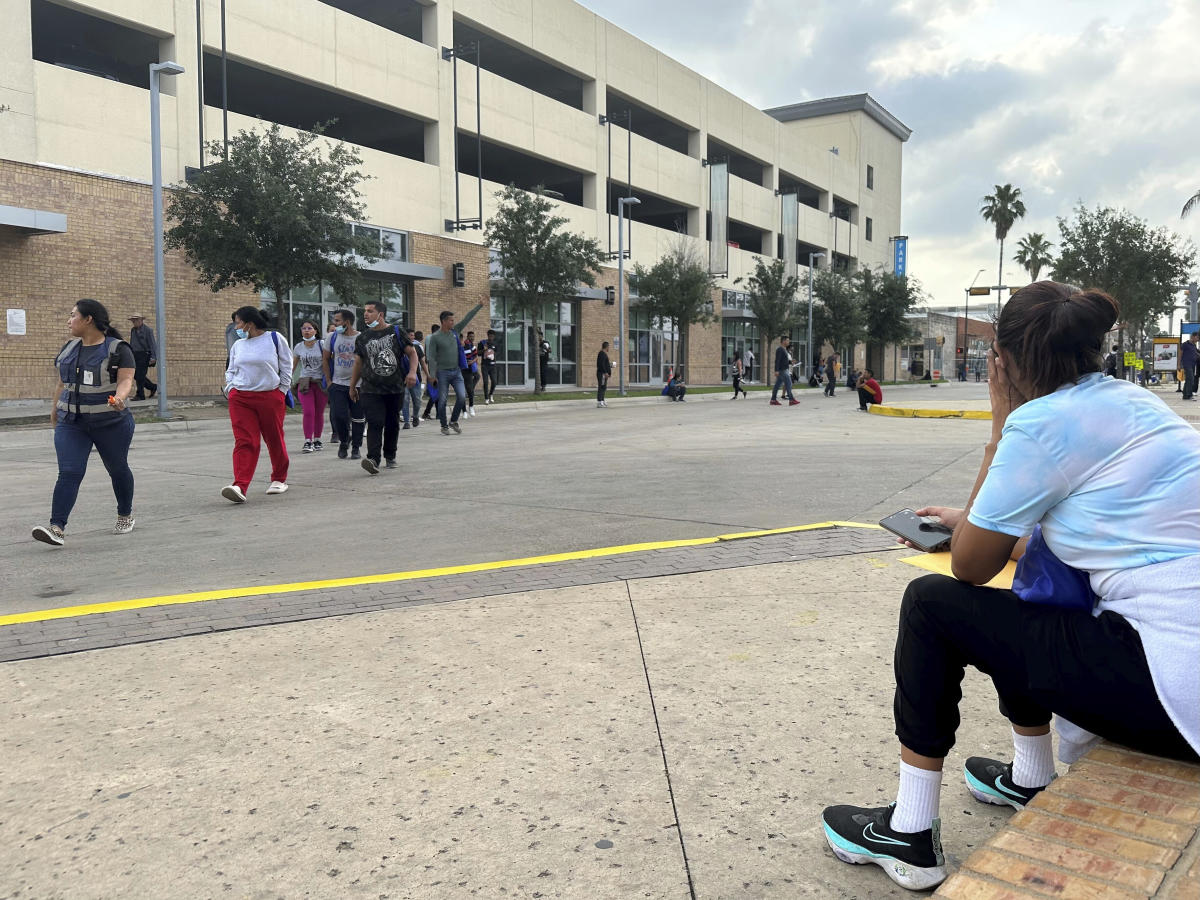

“It was desperation, the cartel,” said Roxana Aguirre, 24, a Venezuelan migrant who sat outside a Brownsville bus station Friday afternoon. “You can’t stand on the street without looking over your shoulder.”

In downtown Brownsville, families from Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti and China wandered aimlessly, carrying their belongings and talking on their cell phones.

Some waited for their buses while others were in limbo, waiting for relatives before making plans to leave but finding no shelter in the meantime. A Venezuelan couple said they slept in a parking lot after being turned away from an overnight shelter.

Officials in Brownsville this week issued a disaster declaration, following other Texas border towns that have done the same despite the sudden surge of migrants, including in El Paso last year.

“We’ve never seen these numbers before,” said Brownsville Police Department spokesman Martin Sandoval.

The redeployment of resources at the border — in one of the busiest industries with a robust border guard workforce — comes as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security prepares to end the use of a public health authority known as Title 42 , allowing them to refuse asylum claims.

The government has deported migrants 2.7 million times under a rule in effect since March 2020 that denies the right to seek asylum under US and international law on the grounds of preventing the spread of COVID-19 . Title 42, as the public health rule is called, will end on May 11 when the US lifts the latest COVID-related restrictions.