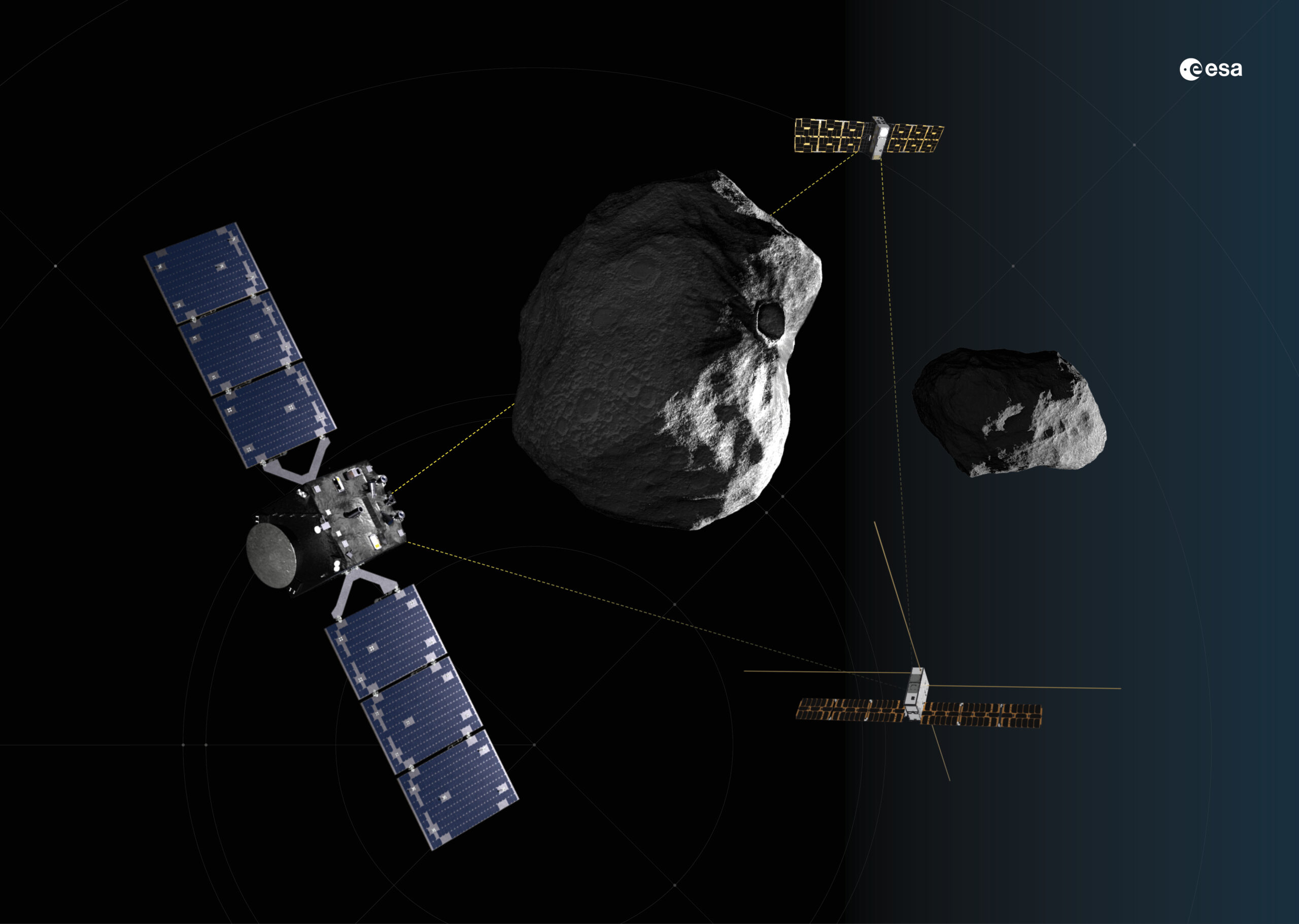

“This is the first time we are sending a spacecraft to a small body, which is actually a multi-satellite system, with one main spacecraft and two CubeSats performing closer operations,” Michel said. “This has never been done before.”

Artist's illustration of the Hera spacecraft with its two deployable CubeSats, Juventas and Milani, near the binary asteroid system Didymos. The CubeSats will communicate with ground teams via radio links to the Hera mothership.

Credit: ESA Science Office

Artist's illustration of the Hera spacecraft with its two deployable CubeSats, Juventas and Milani, near the binary asteroid system Didymos. The CubeSats will communicate with ground teams via radio links to the Hera mothership.

Credit: ESA Science Office

One source of uncertainty, and perhaps concern, about the environment around Didymos and Dimorphos is the status of the debris field that Hubble observed a few months after DART's impact. But according to Kueppers this will probably not be a problem.

“I'm not really worried about possible boulders on Didymos,” he said, recalling the relative ease with which ESA's Rosetta spacecraft navigated around an active comet from 2014 to 2016.

Ignacio Tanco, ESA's flight director for Hera, does not share Kuepper's optimism.

“We didn't hit the comet with a hammer,” said Tanco, who is responsible for keeping the Hera spacecraft safe. “The debris question for me is actually a source of… I wouldn't say it's about concern, but certainly about precaution. It's something that we have to address carefully once we get there.”

“That's the difference between an engineer and a scientist,” Kuepper joked.

Scientists originally wanted Hera to be near the binary asteroid system Didymos before DART's arrival so it could directly observe the impact and its effects. But ESA member states did not approve funding for the Hera mission in time, and the space agency only signed the contract for the construction of the Hera spacecraft in 2020.

ESA first studied a mission like DART and Hera more than twenty years ago, when scientists proposed a mission called Don Quijote to obtain an asteroid deflection. But other missions were given priority in the European space program. Now Hera is on track to write the final chapter in the story of humanity's first planetary defense test.

“This is our contribution from ESA to humanity to help us protect our planet in the future,” said Josef Aschbacher, ESA Director General.