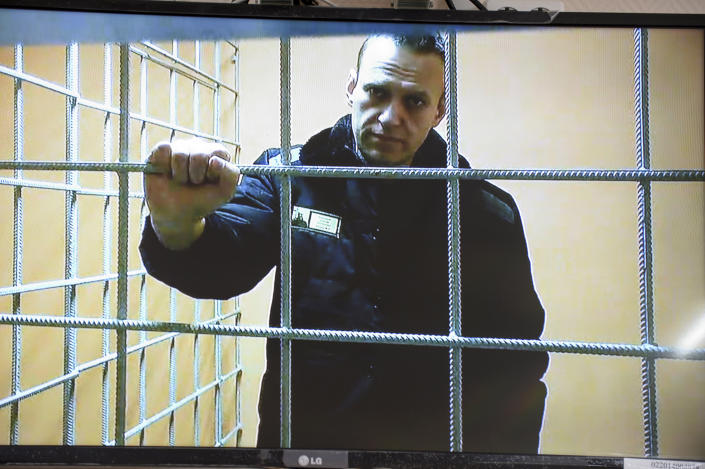

Exactly two years after being arrested on his return to Russia, convicted on fictitious charges in a trial the outcome of which was never in doubt, and taken away to serve an 11-year prison sentence in a brutal penal colony, the dissident politician Alexei Navalny managed a feat that is rare for Kremlin opponents: he survives.

Navalny acknowledged the birthday in a Twitter thread. “I am not going to surrender my country to them and I believe that the darkness will eventually disappear,” He wrote (the messages are sent by his collaborators outside Russia). “But as long as it lasts, I will do everything I can, try to do what’s right and urge everyone not to give up hope.”

Survival has been particularly difficult lately in the remote Melekhovo prison, where Navalny was shipped to in June last year.

That was roughly how in 2009 Russian authorities disposed of Sergei Magnitsky, a tax accountant who had uncovered massive fraud by top Kremlin officials. And given that Navalny is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s most formidable political opponent, he seemed destined for a similar purpose.

But so far, the 46-year-old pro-democracy activist has managed to avoid the plight of Magnitsky and so many other activists, journalists and politicians who have opposed Putin. An important advantage for Navalny is his social media fame. After each visit to the prison, Navalny’s lawyer Vadim Kobzev connects with aides in the West, who then turn his prison messages into lengthy Twitter threads for the public – both in Russia and abroad – to consume.

Earlier this month, Navalny’s health appeared to be deteriorating and outrage reached an extraordinary height. It is impossible to know how much or what impact the outcry had on the Kremlin, which claims to ignore international opinion but closely monitors Western media.

Navalny’s allies believe that if the Kremlin had had his way, he would have been dead three years ago.

In 2018, Navalny unsuccessfully challenged Putin for the presidency, but in the course of that he became a Western icon, a lone voice for freedom in an increasingly unfree country. His cultural prominence, more than his political movement, may have proved more of a threat to Putin, an avid student of Soviet propaganda.

Two years later, Navalny survived a poisoning attempt while flying across Russia. The attempt was almost certainly made by the Kremlin, Western intelligence agencies have concluded. The Kremlin has a long history of suspected poisoning attacks against its critics and defectors.

After recuperating in Germany for several months, Navalny decided to return to Russia. He arrived in Moscow and was promptly arrested, as he, his family and his supporters knew he would become. Authorities said they accused him of failing to appear at a parole hearing, but the allegations themselves were irrelevant, as they often are in Russia.

Aware that he was giving himself over to the same tormentors who had tried to put a deadly poison in his undergarments several months earlier, Navalny seemed unfazed.

“This is the best day of the past five months,” he said in his last moments of freedom, as journalists and well-wishers – and his wife Yulia – crowded around him. “I am home.”

The ensuing trial only drew more attention to his plight and to the deepening authoritarianism of the Putin regime.

For his part, Navalny remained as uninterested as ever. He used his closing statement to deliver a sweeping condemnation of what Russia had become after living under Putin’s rule for 20 years. “We have to fight not only against the lack of freedom in Russia, but also against our total lack of happiness,” he said. “We have everything, but we are an unhappy country.”

Navalny eventually received an 11-year prison sentence for false embezzlement and fraud. He began serving his sentence in the IK-2 penal colony.

At least 1 million Russians perished in Soviet-era gulags, where hardened criminals, political dissidents, free-thinking intellectuals and ordinary people suffered after coming under the Communist Party’s iron grip on public and private life – by filing an innocent complaint. serving on food rations, for example. Though dismantled long ago, evidence of the Gulag system still remains in Russia’s penal colonies.

IK-2 is relatively close to Moscow; the move to IK-6, deeper into the Russian heartland, seemed to herald a more difficult new chapter in Navalny’s incarceration. He was regularly placed in solitary confinement and robbed of winter clothes, a particularly brutal turn in a region where temperatures can freeze for months.

“They are slowly killing him,” Anna Veduta, a US-based vice president of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, told Yahoo News last November.

Then, on the last days of 2022, IK-6 authorities in Melekhovo placed Navalny in isolation for washing his face at 05:24, 36 minutes ahead of schedule. He had to share a cell with a prisoner infected with the flu, who was rampaging through the prison.

“Looks like they’re using him as a biological weapon,” Navalny wrote with his usual gallows humour. No wonder he’s sad. Stay healthy in the new year!”

The message was interrupted by a winking emoji.

Veduta said Navalny’s condition had become “catastrophic” by the second week of January. She described him as “seriously ill – fever, cough and all the horrible flu symptoms. A lawyer brought him medicine, but the prison authorities refused to let him give it to Alexei.”

In an interview on CNN, Navalny’s daughter Dasha described her father’s condition as “worsening by the day”.

Perhaps the most extraordinary plea came from 200 Russian doctors who wrote their names on a letter stating that they could no longer be “indifferent” to the “deliberate harm done” to Navalny. In a country where it is forbidden to describe the invasion of Ukraine as a war rather than by the official euphemism of “special operation”, the letter was a rare display of courage – and an unequivocal insult to Putin, the man who was largely responsible for Navalny’s hardships. .

“We demand an end to the torment of Alexey Navalny,” the doctors wrote.

Other governments also responded to the call.

Germany demanded that Russia provide immediate medical care to Navalny while denouncing the “inhumane prison conditions” that are a staple of Russian prisons, for both high-profile and ordinary prisoners.

In Washington, National Security Council spokesman John Kirby acknowledged to Yahoo News that US officials were monitoring Navalny’s health. “We have seen those concerns — and share those concerns,” he said at a press conference at the White House. “And we will continue to make those concerns clear to the Russian authorities.”

The Kremlin has said nothing about Navalny’s fate, in line with its broader philosophy of pretending opponents of Putin’s authoritarian regime don’t exist. This makes it easier to claim ignorance when those adversaries are poisoned, defenestrated, or otherwise killed in suspicious circumstances.

For Navalny’s backers, the best possible case scenario – at least for now – is that he is too prominent a figure for the Kremlin to kill.

On Thursday, they finally got some encouraging news. Navalny’s lawyer Kobzev said his client’s condition was “stopped getting worse.”

“Navalny greets everyone, thanks for the concern and special thanks to the doctors who attended to him!” said a Twitter post from his lawyer Kobzev late last weekafter the ailing Reformer seemed to have received a small amount of medical care.

He said Navalny had been given antibiotics and his hot water ration had been increased: “Two cups a day.”