In late May, Russian ambassador Nikolai Korchunov informed state media that the situation in the Arctic was becoming dangerous. He wasn’t talking about melting polar ice as a result of climate change. Instead, he warned of “a deeply disturbing trend that is turning the Arctic into an international arena of military operations,” and accused NATO of expanding its presence in the region.

“That’s a typical Russian play,” retired Finnish Major General Pekka Toveri told Yahoo News. “Western activity in the Arctic was very mild.” In March, however, NATO held an “Exercise Cold Response” in Norway. With 35,000 fighters from 28 countries it was NATO’s largest Arctic exercise in 30 years. Yet, unlike Russia, the alliance has no new plans for permanent troops or military bases in the region, Toveri said, acknowledging that “more patrols and more exercises have given Russia reason to point the finger and claim that the West is the problem.”

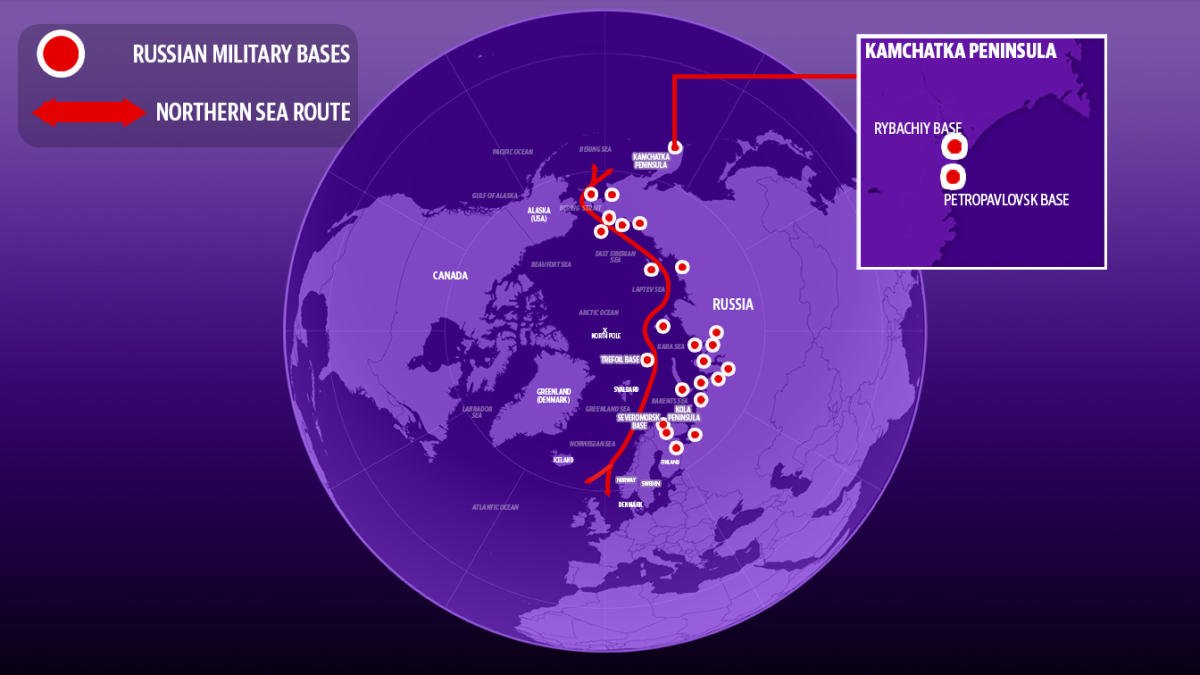

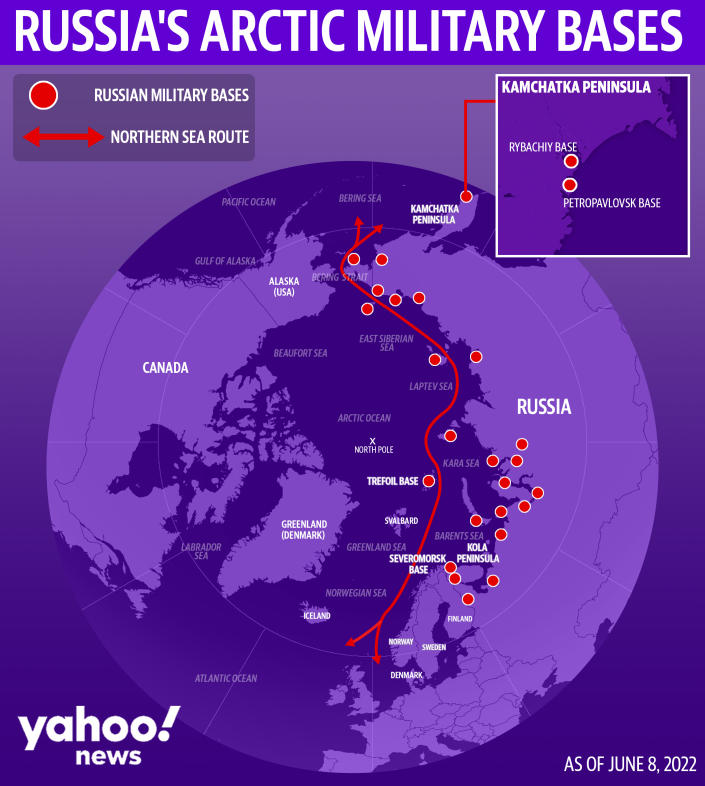

Western experts say Russia, the largest of the seven countries surrounding the Arctic, is behind the militarization of the mineral-rich region, which provides 20% of Russia’s GDP. Over the past decade, the Kremlin has renovated shuttered Soviet bases, chained dozens of defensive outposts (some counts over 50) from the Barents Sea to areas near Alaska, and built new facilities such as the state-of-the-art Trefoil, the most northern base which became fully operational last year. The US and NATO have watched with dismay as Russia has established a new “Arctic Command” and four new Arctic brigades, refurbished airports and deep-water ports, and continues to launch fake military attacks on Scandinavian countries between blocking of GPS and radar during NATO. assignments. According to the US State Department, it has also tried “new weapons systems” in the Arctic.

“We have been seeing increasing Russian military activity in the Arctic for some time now,” a senior State Department official told Yahoo News. The situation is deteriorating, however, and not just because Russia continues to test new hypersonic weapons in the Arctic, launching a hypersonic missile there just days after Korchunov made his comments. Before the end of the year, the foreign ministry official added, Russia plans to launch 19 more tests, including new weapons. “Seeing Russia’s aggressive and unpredictable behavior, especially since the invasion of Ukraine, has really heightened concerns about Russian activity in the far north,” the official said.

With relations between Moscow and Western governments in the frostiest in decades following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, analysts are questioning whether the Arctic will become the next powder keg. Russia’s expansion of bases, weapons tests and more manpower in the Arctic comes as Finland and Sweden have applied for NATO membership. If accepted, that would further isolate Russia in the Arctic, making it the only non-NATO country in the region, further increasing the likelihood of accidental incidents, analysts say.

Author of the recently released report “The Militarization of Russian Polar Politics,” Mathieu Boulègue, a researcher in the Russia and Eurasia Program at Chatham House, told Yahoo News that his biggest fear is a nuclear accident in the region.

“If you look at the long list of nuclear assets — be it icebreakers, strategic submarines, floating nuclear power plants or spent nuclear fuel — there is a high risk of nuclear incidents,” he said. “In peacetime, such incidents are mitigated if you talk to the various stakeholders. But the problem is we don’t really talk [with] Russia very well these days. This increases the risk of miscalculations and errors even further.”

The Kola Peninsula, for example, an inch of Russian land the size of Kentucky bordering Finland, is the most nuclear-generated place on Earth. The headquarters of the Russian Northern Fleet, which accounts for two-thirds of Russia’s second-attack maritime nuclear capabilities, the Kola Peninsula marks the entrance to Russia’s Arctic and has three military bases and nuclear weapons storage depots.

However, another third of Russia’s naval nuclear weapons are in the far east of the Arctic, Boulègue added — with the Russian Pacific Fleet, headquartered in Vladivostok, but some ships based in Kamchatka, just across from Alaska. Those facilities could pose future problems for the US, Boulègue said, by creating “a flashpoint of tension should Russia decide to contest US access to the Arctic”.

Ian Williams, deputy director of the Missile Defense Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, also points to Wrangel Island — 500 miles from Alaska — where Russia has installed a new air search radar system and may be renovating an airport, as well as bases in eastern Siberia. . “They have plenty of places to store stuff if they want to threaten Alaska,” he noted.

Growing concerns about Russia’s activities in the Arctic, where it is pursuing a new Northern Sea route made possible by melting ice due to climate change, has prompted US military forces to rethink their Arctic strategies. Last year, the military published Regaining Arctic Dominance, the first strategic plan for the far north. Army personnel have also taken up training in Alaska more often, learning how to fight in the unforgiving Arctic — where temperatures can drop to minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

The US Navy conducts arctic maneuvers with ships and submarines and more — and the Air Force sends the bulk of its F-35s to Alaska, saying the state will be “home to more advanced fighters than any other location in the world. ” Congress approved funding for six new “icebreakers,” vessels that can plow through frozen water. And new satellites intended to improve polar communications and provide new “eyes” on Russia are being launched, along with new radar systems being built from Alaska to Denmark.

All these moves are welcomed by Toveri, who believes the West cannot appease Putin and expects to “get the peace dividend of the Cold War era”. He added that after the fall of the Soviet Union, many Scandinavian countries, including Sweden, have shrunk their armies and cut spending, while countries like Denmark shut down their missile defense radar systems, which they are rebuilding again.

However, such moves confuse Russia, which it considers provocative. Earlier this year, Russian spy planes violated the airspace of Sweden and Denmark. For example, in March 2018 and February 2019, Russian bombers targeted Norway’s Globus radar system in mock air strikes, firing at the domed structures before returning abruptly. However, Russia’s problems with Norway extend far beyond its espionage activities.

The Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, which lies halfway between Russia and Greenland, is a good example. In addition to Russia’s historical territorial claims to the area, the archipelago is also home to a radar and satellite system capable of tracking ballistic missile paths, which is seen as key to NATO communications. Russian politicians occasionally threaten to just take the archipelago, as they did with Crimea.

“If there is a dispute in the Arctic, it will probably be here,” CSIS’s Williams said, and the US State Department official underlined those concerns.

Timo Koivurova, research professor at the Arctic Center at the Finnish University of Lapland, told Yahoo News that he regrets that “relations between Russia and Western states have deteriorated and that thinking about the Cold War has taken over.” However, he wonders if the concerns are overblown. “If you talk to a security-minded scientist, he might argue that World War III comes from the Arctic. But it’s very hard for me to imagine that because when you think about Russia’s military objectives in the region, there aren’t many military incentives for Russia, other than this kind of balancing with NATO.”

Williams also sees many parts of the Arctic picture undecided, including the US military commitment to the region, which is an expensive undertaking.

“Operating an F-35 in the Arctic is a lot more expensive than having it operated in Hawaii,” he said. He noted that the US is concerned about Russia’s strong armament of the Northern Sea Route, an act that the US believes would violate international maritime law. “The big question is: would we expand in that area? At the moment it is an open question.”

“The last thing Russia needs is a hot war in the Arctic,” Nima Khorrami, a research associate at the Arctic Institute, told Yahoo News. “Because if that happened, no one would come to invest.” And right now, Putin, who has imprinted the idea of Russia’s Arctic identity into the national psyche, wants Asian investment in the region, he said. Any kind of military confrontation, Khorrami added, “and the grand strategy of turning the Northern Sea Route into a new Suez Canal is gone.”