Does getting an end-of-year bonus or pay increase make you happier? Does the lift it gives you tend to fade quickly, especially if others around you have also won in the annual compensation sweepstakes?

If the answer is that an increase in income does not greatly improve your sense of well-being, then you are proof of the Easterlin Paradox, the economic theory that more money will not buy more happiness in the long run. .

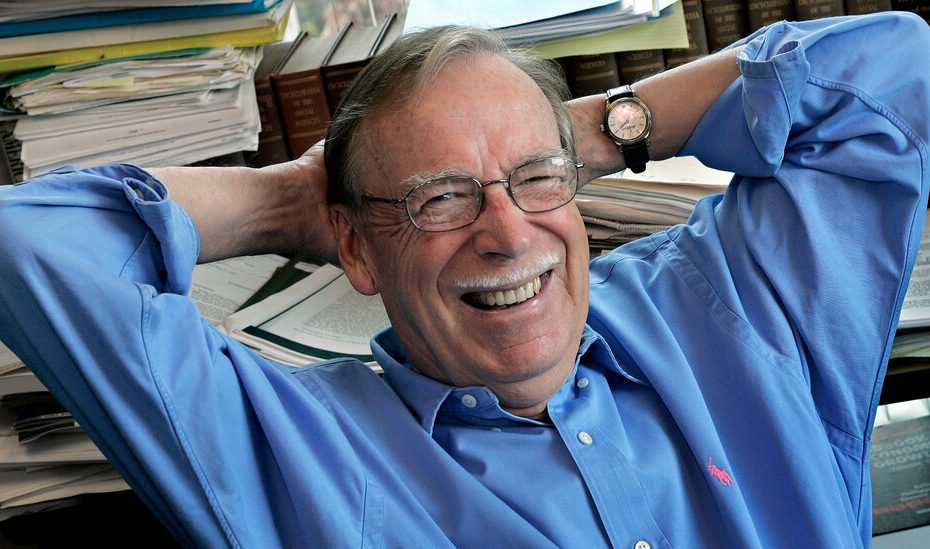

The paradox was put forward by Richard A. Easterlin, an economist, a demographer and a pioneering figure in the field of academic research on happiness. The University of Southern California, where he was professor emeritus, called him the 'father of happiness economics' when announcing his death.

Mr. Easterlin died on December 16 at the age of 98 at his home in Pasadena, California.

Mr. Easterlin's work challenged both conventional wisdom and a core economic principle: that economic growth in a society leads to an overall improvement in feelings of well-being.

Economists, policymakers, and ordinary citizens have long assumed that increasing a country's gross domestic product—its total economic output—improves the happiness of its people.

But in the 1970s, Mr. Easterlin, then at the University of Pennsylvania, published research showing that even though incomes in the United States had risen dramatically since World War II, Americans said in surveys they were no happier.

He found similar results for Japan, which had become one of the richest countries in the world after rebuilding from wartime destruction. Although Japanese incomes increased fivefold between 1958 and 1987, Japanese people said they were no happier either.

Mr. Easterlin identified what was called the Easterlin Paradox in a 1974 article, “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?”

Examining opinion polls from 19 countries, he found that rich people were happier than poor people. But as incomes rose, people's happiness did not rise proportionately.

When it comes to money, Mr. Easterlin noted, people's happiness depends on how well off they are compared to those around them. As individuals become wealthier and their friends, coworkers, or neighbors become wealthier as well, they may not feel like they've gained anything, just that they're keeping up with the Joneses.

“Even though I'm happier because my income is up, I'm less happy because everyone else is up too,” he explained in a 2021 interview recorded by the University of Southern California. “So the result is that people cannot enjoy an improvement in their income as a source of happiness due to social comparison.”

Easterlin's paradox has been cited thousands of times by other scholars, and has passed into popular usage – confirming to anti-materialists and growth-at-any-cost skeptics that money cannot buy happiness, as the cliché goes.

Most radically, some economists have said that the paradox implies that policymakers should not try to increase GDP because this would make little difference to people's sense of well-being.

In 2008, the paradox was attacked by a pair of rising young economists, Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson, who argued in an article that a broader series of polls conducted in the 34 years since Mr. Easterlin first published his thesis undermined his conclusions . They found evidence indicating that economic growth in countries was indeed linked to increasing happiness.

Daniel Kahneman, a Princeton psychologist and a Nobel laureate in economics, told The New York Times that year: “There's just a tremendous amount of accumulated evidence that the Easterlin paradox may not exist.”

Mr. Easterlin responded that while he agreed that people in richer countries reported being more satisfied with their lives than people in poor countries, he was skeptical that wealth explained their happiness. He called the work of Mr. Wolfers and Ms. Stevenson “a very rough draft without sufficient evidence.”

“Everyone wants to show that the Easterlin paradox doesn't hold up,” he added. “And I'm perfectly willing to believe it won't last. But I would like to see a substantiated analysis that shows that.”

In 2009, when Mr. Easterlin received the IZA Prize for Labor Economics from the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn, Germany, Mr. Wolfers wrote in a blog article for the “Freakonomics” podcast that he and Mr. Easterlin “disagreed are on a pretty important issue,” but he went on to call Mr. Easterlin the father of the economic analysis of happiness.

“His research has inspired much of my own interest in the economics of happiness,” Mr. Wolfers wrote.

Richard Ainley Easterlin was born on January 12, 1926 in Ridgefield Park, NJ, the son of John and Helen (Booth) Easterlin. His father became commissioner of Broward County, Florida.

Richard received a master's degree in engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ, in 1945, but then switched to economics. He received a master's degree in economics in 1949 and a Ph.D. in 1953, both from the University of Pennsylvania. He remained at Penn teaching economics for more than thirty years, including three stints as chairman of the economics department.

In 1982, he moved west to teach economics at USC, where he became a university professor at the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. He was granted emeritus status in 2018.

In addition to his work on economics and happiness, Mr. Easterlin analyzed demographic trends. He proposed the Easterlin effect, which means that baby booms and baby busts happen for economic reasons.

When there are enough jobs, he wrote, couples marry young and the country's fertility rate rises; when jobs are scarce, marriage is postponed and fertility falls. According to him, the baby boom of 1946-1965 occurred because job opportunities abounded, incomes improved, and confidence among couples to start a family increased. The opposite factors converged in the baby crisis of the late 1960s and 1970s, he said.

Mr. Easterlin is survived by his wife, Eileen Crimmins, professor of gerontology at USC, whom he married in 1980; his children, John, Nancy, Susan, Andrew, Matthew and Molly Easterlin; and eight grandchildren. He was previously married to Jacqueline Miller.

Although Mr. Easterlin long believed that no government policy would increase the sum of human happiness, he changed his mind in the 1990s, recognizing that factors other than income were important to a sense of well-being.

“Improvements in income have relatively little effect on happiness,” he said in the 2021 USC interview in his mid-90s, “while improvements in health and family life have a substantial impact.”