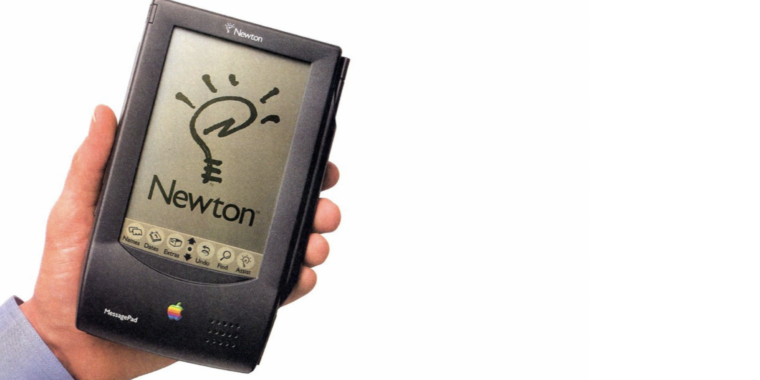

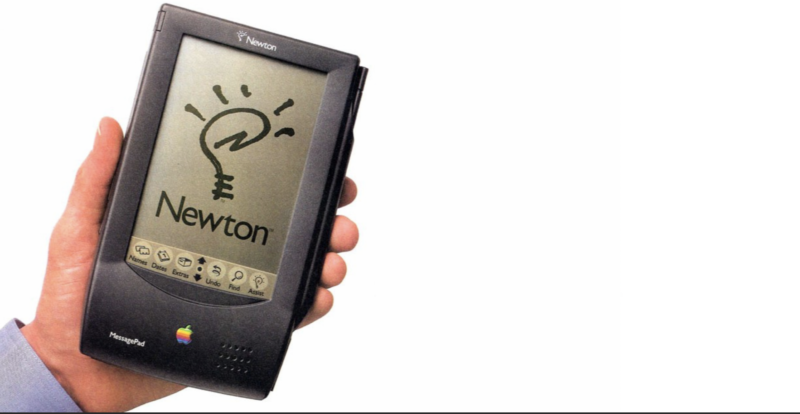

Thirty years ago, on May 29, 1992, Apple announced its most groundbreaking and revolutionary product to date, the Newton MessagePad. It was released with much fanfare a year later, but as a product it could only be described as a flop. Much mocked in popular culture at the time, the Newton became a billboard for expensive but useless high-tech gadgets. Although the device improved dramatically over time, it failed to gain market share and was discontinued in 1997. But while the Newton was a failure, it prompted Apple engineers to create something better — and in some ways led to the creation of the iPad and the iPhone.

The vision

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple in 1976, had expelled marketing guru John Sculley from PepsiCo in 1983 to become Apple’s new CEO. However, their relationship broke down and Jobs resigned from Apple two years later after a bitter power struggle. Although Sculley made Apple profitable by cutting costs and introducing new Macintosh models, he felt lost without the visionary founder of Apple. So when Apple colleague Alan Kay stormed into Sculley’s office and warned him that “next time won’t be Xerox” (to borrow ideas from), he took it seriously.

In 1986, Sculley commissioned a team to create two “high-concept” videos for a new type of computing device that Apple might build in the future. These “Knowledge Navigator” promos showed a foldable, tablet-like device with a humanoid “virtual assistant” interacting through spoken instructions. While some mocked the impracticality of these sci-fi vignettes, they got Apple employees thinking and thinking about the future of computers.

Meanwhile, Apple engineer Steve Sakoman was bored after the launch of the Macintosh II. He wanted to make a portable device like the groundbreaking PC laptop he built for Hewlett-Packard. To prevent him from leaving Apple, Vice President Jean-Louis Gassee had him set up a “skunkworks” project to pursue his dream. But he didn’t want to make just any Macintosh laptop. He had a vision of a tablet-like device, the size of a folded A4 sheet, that could read people’s handwriting.

The dream starts to slip away

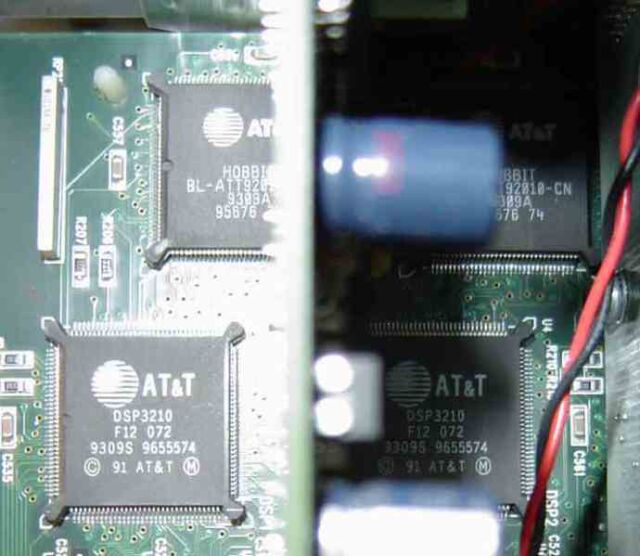

The technology to make such a device didn’t exist when the Newton Project began in 1987, so Sakoman contacted AT&T and hired the company to design a power-efficient version of its CRISP CPU, which became known like the AT&T Hobbit.

Unfortunately, the Hobbit wasn’t nearly as agile and smart as its namesake. The CPU was full of bugs, unsuitable for our purposes, and too expensive, said Apple Chief Scientist Larry Tesler. The original Newton design required three Hobbit CPUs to run, end-user costs were close to $6,000, and the device wouldn’t even be ready for at least five years. Handwriting recognition software, a major selling point for the device, also progressed slowly.

Development of the Newton had stalled and Sakoman was beginning to lose hope that he would ever get off. In 1990, he left Apple with Gassee to form Be, Inc. which made its own desktop computers and the BeOS operating system.

At the same time, another “top secret” Apple division was also working on unique wearable devices and software codenamed “Pocket Crystal”. Instead, he suggested turning Pocket Crystal into a separate company (which became General Magic) and refocusing the Newton project with new hardware and new leadership.