Because we’re members of the group, it’s easy to think of vertebrates as the pinnacle of evolution, a group capable of producing bats, birds, and giant whales in addition to ourselves. But when they first evolved, vertebrates were anything but certain. They split from a group that lived in the mud and didn’t have to distinguish the top from the bottom or the left from the right, and so they ended up losing an organized nerve cord. Our closest non-vertebrate relatives repaired a nerve cord (on the wrong side of the body, of course), but couldn’t be bothered with niceties like a skeleton.

Exactly how vertebrates got out of this has not been clear, and the likely lack of a skeleton in our immediate ancestors means we don’t have many fossils to clear things up.

But in Thursday’s Science issue, researchers have re-evaluated some puzzling fossils dating to the Cambrian period, settling several arguments about which characteristics the yunnanozoans had. The answers include cartilaginous structures that supported gills and a possible ancestor of what became our lower jaw. During the process they show that yunnanozoans are probably the earliest branch of the vertebrate tree.

Yunnanowatans?

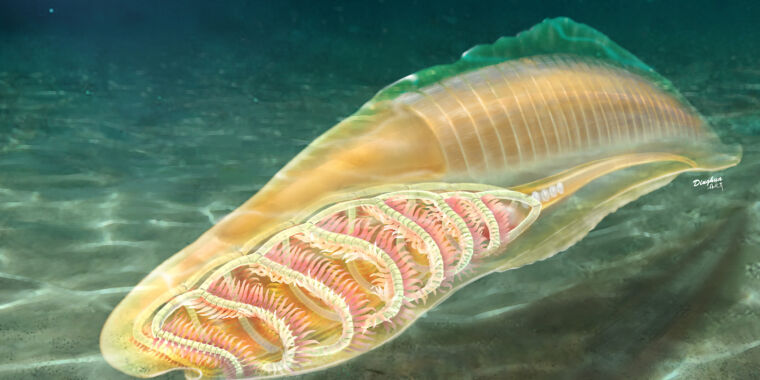

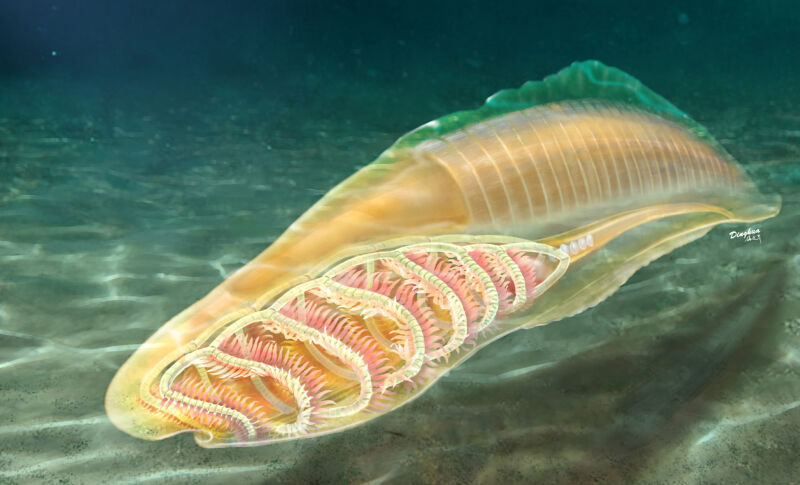

You can get an idea of what a yunnanozoan looks like the picture above. The soft tissue along its flanks was segmented, a feature of both of our closest living invertebrate relatives (the amphioxus or lancet), and is present in vertebrate embryos, but is generally lost as they develop into adults. Near the animal’s head — and it has a distinct head and mouth — there is also a series of curved structures much like the similarly positioned gill arches found on the heads of modern fish.

If that interpretation is correct, it would mean: yunnanozoans are very similar to an amphioxus, but have a characteristic otherwise only found in modern vertebrates. This would mean that it retains functions essential to understanding the origin of vertebrates.

But the “if” that starts with the previous paragraph is a big one. Many people in the field disagreed with this interpretation and posted yunnanozoans elsewhere. Or rather several elsewhere, depending on who exactly was arguing. Some place them in the same group as the amphioxus. Others propped them up further away from vertebrates, placing them with the group of mud dwellers who don’t have two of the body axes found in vertebrates. Still, others suggested they were the ancestors of a huge group of organisms, including things like sea urchins.

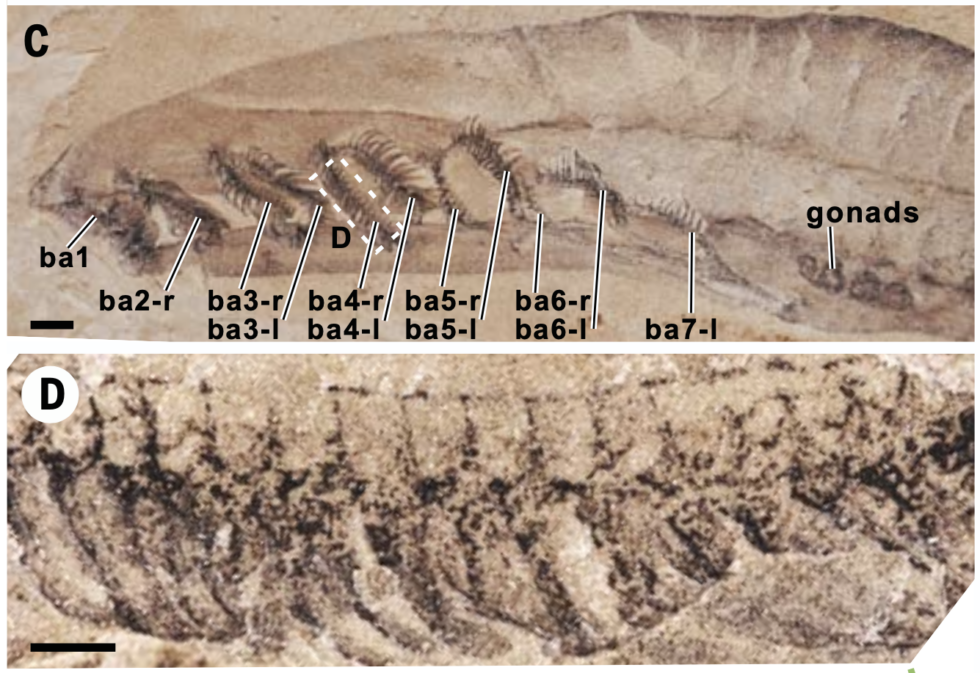

A small team from China has now tried to settle these quarrels. It does this in part by mapping more than 100 new fossils of the species. But a big part is that they used some of the most advanced imaging techniques available. That included three-dimensional X-ray imaging, electron microscopy and a technique that bombards microscopic areas of the sample with electrons and then uses the emitted light to determine which elements are present.

Tian et. already.

I’m showing one of the images from the article below to give you an idea of the detail these imaging techniques provide.