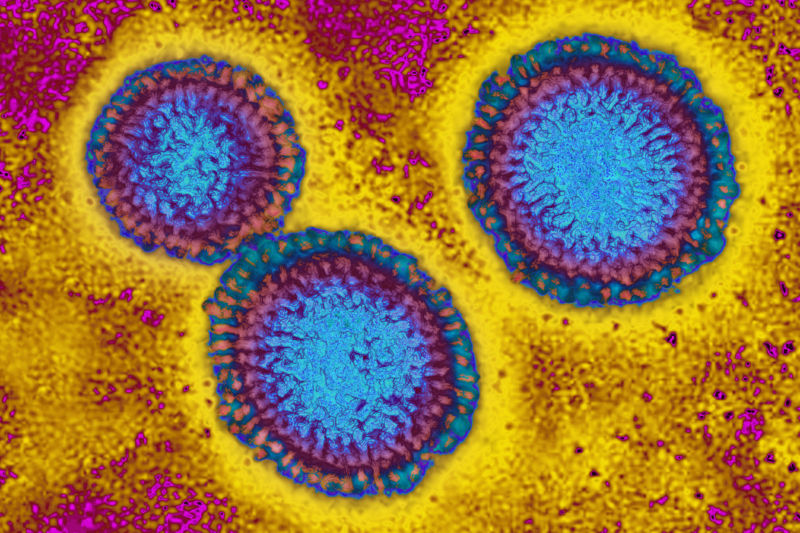

A person in Missouri who has never had contact with animals has been infected with the H5 bird flu strain, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (MDHSS) announced Friday night.

MDHSS reported that the individual, who has underlying medical conditions, was admitted to the hospital on August 22 and tested positive for influenza A virus. Further testing at the state public health laboratory indicated that the influenza A virus was an H5 strain of bird flu. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has now confirmed this finding and is conducting further testing to determine if it is the H5N1 strain currently causing a widespread outbreak among U.S. dairy cows.

It remains unclear whether the person’s bird flu infection was the cause of the hospitalization or whether the infection was discovered by chance. The person has since recovered and been discharged from the hospital. In its announcement, MDHSS said that no other information about the patient will be released to protect the person’s privacy.

The report marks the 15th human case of an H5-type bird flu infection in the country since 2022. But the case stands out — and is quickly causing alarm online — because the man reported no contact with animals. All 14 previous cases occurred in farm workers who had contact with dairy cows or poultry known to be infected with H5N1.

The finding in a person who has not been exposed to such a disease suggests that the H5N1 virus is spreading from person to person without being detected, or that spread is occurring from an undetected animal source.

While the case raises concerns, some infectious disease experts are reluctant to sound the alarm until more data is available about the case and possible exposure.

“[U]“Until such data is collected and analyzed, my concern is only slightly elevated,” Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and founder and deputy director of the Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics at the CDC, said online.

“I am pleased that this case was detected through existing surveillance systems, which bodes well for our ability to identify additional cases in the future,” she added. “Federal, state, and local health officials maintained influenza surveillance throughout the summer months in response to the H5 situation, and that was absolutely the right move.”

But Rivers, like many of her colleagues, has long worried about the possibility that H5N1 could jump to humans and cause a pandemic.

To date, H5N1 is known to have infected 197 flocks in 14 states. Missouri has reported no infected flocks, but has reported infected poultry farms.