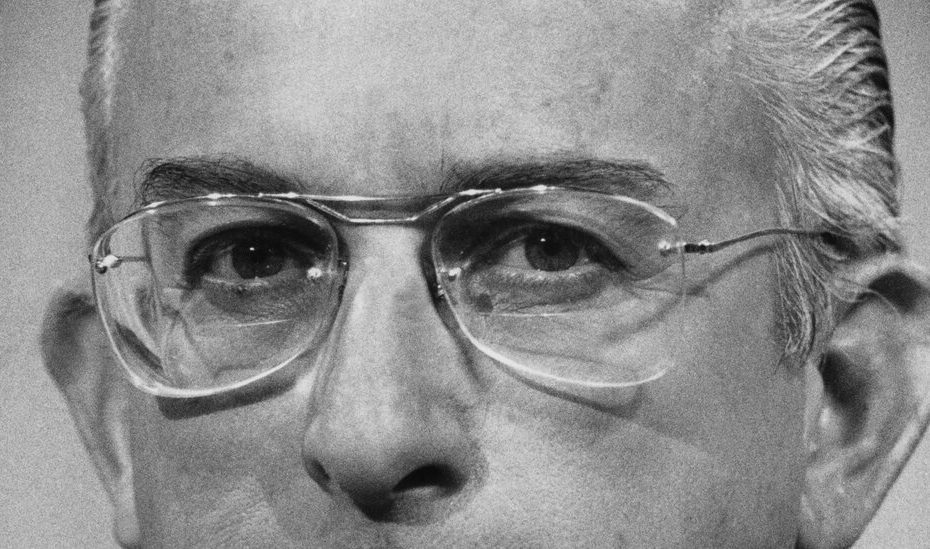

Paul F. Oreffice, who as embattled head of Dow Chemical grew and diversified the company while denouncing Vietnam veterans over Agent Orange, argued that the chemical dioxin was harmless and oversaw the production of silicone breast implants known to leak , died on December 26 at his home in Paradise Valley, Arizona. He was 97.

His family confirmed the death.

Mr. Oreffice (pronounced like opening) spoke in staccato, rapid sentences, and they were often deployed to push back environmentalists, politicians and journalists in the 1970s and 1980s, an era when the environmental movement gained momentum by focusing on toxic chemicals in the air and water.

Under his 17-year leadership, which included the titles of president, CEO and chairman, Mr. Oreffice endured intense controversy.

His PR instincts were for confrontation, not reconciliation. He had an intense aversion to what he perceived as government interference in business, which he traced back to having grown up in Italy under Mussolini.

“I've seen what over-management can do,” he told The New York Times in 1987. “I was born under a fascist dictatorship and my father was imprisoned because of it.”

Mr. Oreffice took control of the Dow USA division in 1975, when the company's public image was tarnished by campus protests in the 1960s that had defamed the company as the maker of the inflammatory drug napalm, which was widely used in Vietnam.

When Dow withdrew from apartheid South Africa under shareholder pressure in 1987, Mr. Oreffice said: “I'm not proud of it. I think we should have stayed and fought.”

In 1977, when Jane Fonda ripped Dow in a speech at Central Michigan University, not far from Dow headquarters in Midland, Michigan, Mr. Oreffice the company's donations to the school. He wrote to the president that he could not support Ms. Fonda's “poison against free enterprise.”

Instead, Mr Oreffice financed the campaigns of anti-regulation politicians. And he sued the Environmental Protection Agency for conducting aerial surveillance of Dow's sprawling Midland plants while the company refused an on-site inspection.

The case ended up before the United States Supreme Court, which ruled in 1986 against the company, which at the time was the second-largest American chemical manufacturer after DuPont. (The companies merged in 2017 and then split into three companies.)

In 1983, Representative James H. Scheuer, Democrat of New York, announced that Dow had been allowed to redact an EPA report on the leakage of dioxin, one of the most toxic substances ever manufactured, from its Midland plants to the Tittabawassee and Saginaw Rivers. and Saginaw Bay.

EPA regional officials told Congress that their superiors in the Reagan administration ordered the changes to meet Dow's demands. Mr. Oreffice, appearing on NBC's Today show, offered a sweeping resignation.

“There is absolutely no evidence that dioxin causes any harm to humans, other than causing something called chloroacne,” he said. “It's a rash.”

His statement brushed aside evidence that dioxin was extremely dangerous to laboratory animals and research showed it was linked to a rare form of soft tissue cancer in humans.

A former Dow president, Herbert Dow Doan, a grandson of the company's founder, told a public relations publication, Provoke Media, in 1990 that Mr. Oreffice's style was not tailored to mollifying critics. “The reason is partly ego, partly pride,” he said. “Paul tends to push his position so far that some people say he is arrogant.”

There is no doubt that Mr. Oreffice's willpower also boosted Dow's business, which in the 1970s was overly dependent on commodity chemicals such as chlorine. When a glut of low-priced petrochemicals flooded the global market in the early 1980s, he aggressively transformed Dow by diversifying into consumer products, such as shampoos and the cleaning fluid Fantastik, and entering foreign markets. In 1987, Dow posted record profits of $1.3 billion (about $3.5 billion in today's currency).

At the same time, the company's image was further tarnished by a class action lawsuit on behalf of 20,000 Vietnam veterans and their families against Dow and other makers of Agent Orange. The lawsuit, filed in 1979, alleged that dioxin in Agent Orange led to cancer in combat veterans and genetic defects in their children.

Dow argued that it created Agent Orange at the government's request and was not responsible for how it was used. But in 1984, without admitting liability, the company and other makers of Agent Orange settled the lawsuit for $180 million, with the proceeds going to veterans and their families.

In another controversy, Dow Corning, a joint venture between Dow Chemical and Corning Inc., released documents in February 1992 showing that it had known since 1971 that silicone gel could leak from the breast implants it made.

Tens of thousands of women had sued the company, claiming their implants had given them breast cancer and autoimmune diseases. Dow Corning agreed to a $3.2 billion settlement after the company was forced to file for bankruptcy protection.

In 1999, an independent study by a division of the National Academy of Sciences concluded that silicone implants do not cause serious diseases.

Paul Fausto Oreffice was born on November 29, 1927 in Venice. His parents, Max and Elena (Friedenberg) Oreffice, moved the family to Ecuador in 1940 when Mussolini declared war on Britain and France. Paul came to the US in 1945 and attended Purdue University with fewer than 50 words of English at his disposal.

He graduated in 1949 with a BS in chemical engineering, became a naturalized citizen and, after two years in the Army, went to work for Dow in 1953.

“When I walked into Midland, Michigan, this was 'WASP' country, and I was a 'W' but I wasn't an 'ASP,'” he told The Washington Post in 1986. “I spoke with an accent and I combed my hair straight back, which just didn't happen.”

Mr. Oreffice represented Dow in Switzerland, Italy, Brazil and Spain before being recalled to the company's Midland headquarters in 1969 and appointed financial vice president of the company. He became president of Dow Chemical USA in 1975 and was then promoted to president and CEO of parent company Dow Chemical Company in 1978. In 1986, he added the title of chairman.

To the surprise of many observers, in the mid-1980s, Dow poured millions of dollars into a public relations campaign to improve its image, including a new slogan: “Dow lets you do great things.”

Under company policy, Mr. Oreffice resigned as president and CEO in 1987, when he reached the age of 60. He retired as chairman in 1992.

He is survived by his wife of 29 years, Jo Ann Pepper Oreffice; his children, Laura Jennison and Andy Oreffice; six grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

In retirement, Mr. Oreffice pursued a passion for thoroughbred racehorses, investing in Kentucky Derby starters and spending summers in a home in Saratoga Springs, NY. He was partner in a Preakness Stakes winner, Summer Squall, and a Belmont Stakes winner, Palace Malice.

In 2006, he published a memoir about his rise from an immigrant with little English to a business titan. He called it 'Only in America'.