It probably sucked to be a Roman soldier guarding Hadrian's Wall around the third century AD. W. H. Auden imagined the likely harsh conditions in his poem “Roman Wall Blues,” in which a soldier complains of the constant wet wind and rain with “lice in my tunic and a cold in my nose.” We can now add chronic nausea and bouts of diarrhea to his list of likely problems, thanks to parasitic infections, according to a new paper published in the journal Parasitology.

As previously reported, archaeologists can learn a lot by studying the remains of intestinal parasites in ancient feces. For example, in 2022 we reported on an analysis of soil samples collected from a stone toilet found in the ruins of a chic 7th century BC villa just outside Jerusalem. That analysis revealed the presence of parasitic eggs of four different species: whipworms, beef/pork tapeworms, roundworms and pinworms. (It is the first mention of roundworm and pinworm in ancient Israel.)

Later that same year, researchers from the University of Cambridge and the University of British Columbia analyzed the residue on an ancient Roman ceramic pot excavated from the site of a 5th-century CE Roman villa in Gerace, a rural district in Sicily. They identified the eggs of intestinal parasitic worms commonly found in feces – strong evidence that the 1,500-year-old pot in question was most likely used as a chamber pot.

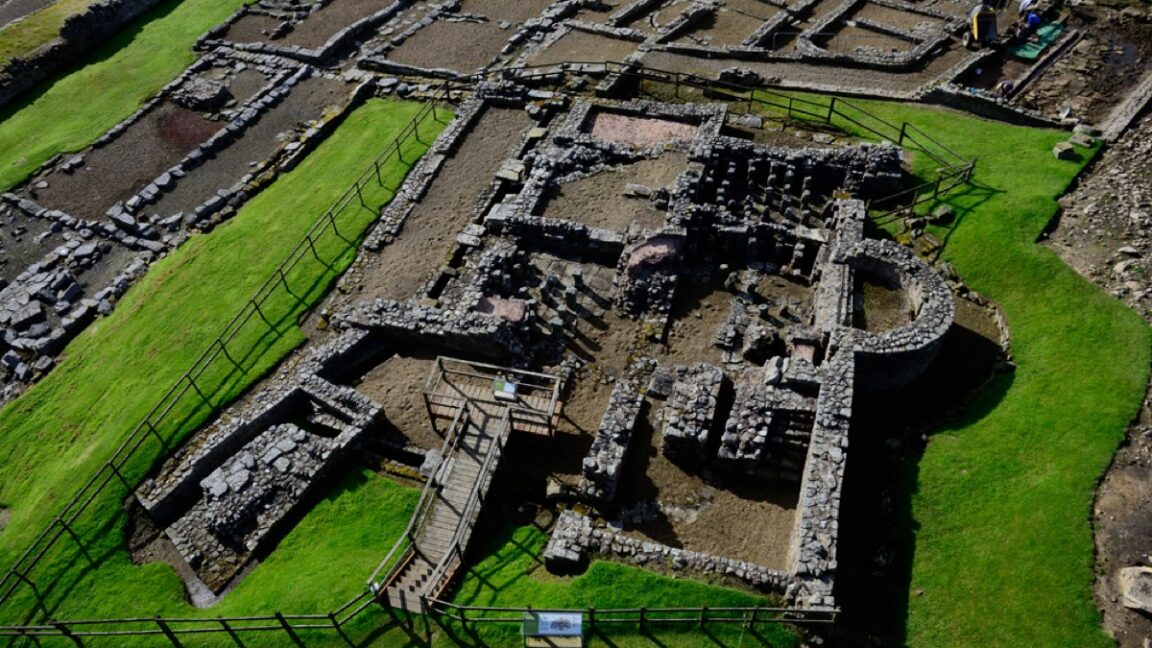

Other previous studies have compared fecal parasites found in hunter-gatherer and farming communities, revealing dramatic changes in diet, as well as shifts in settlement patterns and social organization that coincided with the rise of agriculture. This final article analyzes sediment collected from the sewage drains of the Roman fort at Vindolanda, just south of the defensive fort known as Hadrian's Wall.

An antiquarian named William Camden recorded the existence of the ruins in a 1586 treatise. Over the next 200 years, many people visited the site, discovering a military bathhouse in 1702 and an altar in 1715. Another altar found in 1914 confirmed that the fort was called Vindolanda. Serious archaeological excavations at the site began in the 1930s. The site is best known for the so-called Vindolanda Tablets, one of the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain – and for the 2023 discovery of what appeared to be an ancient Roman dildo, although others have claimed the phallic-shaped artefact was probably a drop spindle used for spinning yarn.