Pablo Eisenberg was only 7 years old in 1939 when he boarded an American liner in Bordeaux with his parents and younger sister as the Nazis were about to invade France. But young as he was, their nail-biting escape nonetheless instilled in him a lifelong devotion to powerless people left behind.

That was reflected in 1973, after years of serving the underprivileged in government and the non-profit sector, when he wrote an article for a philanthropic magazine that would change his professional career and shake up the world of charity.

In the article, published in Grantsmanship Center News, Mr. Eisenberg, who died Oct. 18 at age 90, called on major foundations, individual donors, charities and philanthropies in general to be more socially responsible, transparent, accountable and equitable. in determining who received their generosity. To further the cause, he established a non-profit consulting firm to provide technical assistance to grassroots community organizations seeking philanthropic assistance.

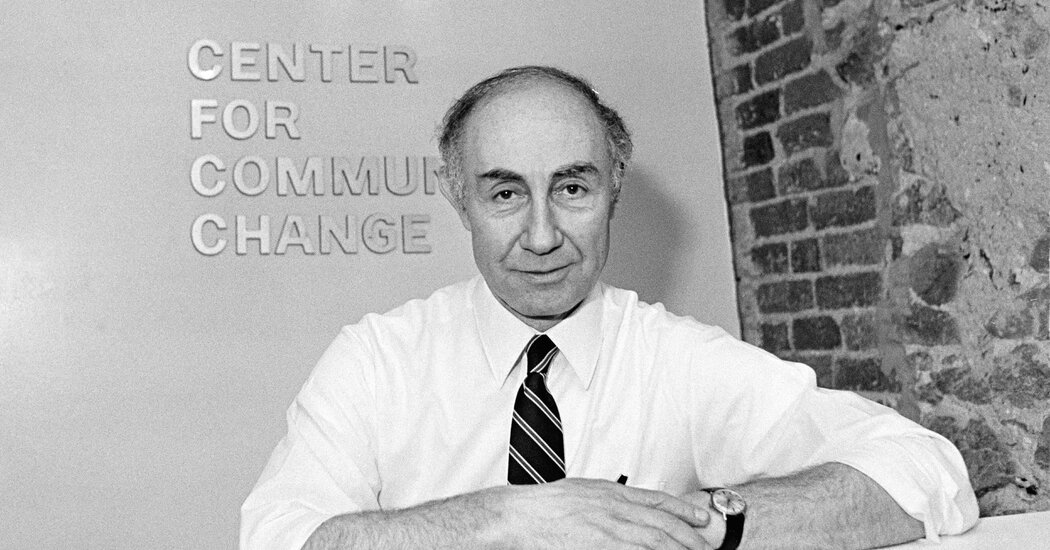

“The rush to leave France deeply affected him,” said Mary Lassen, a former director of what is now Community Change, a Washington-based advocacy group for the poor originally funded by the Ford Foundation, which Mr. Eisenberg led as executive. director. from 1975 to 1998. “He wanted to change the world. He had a passion for improving the lives of ordinary people.”

In the article, which received national attention, Mr. Eisenberg posed a simple question: Who benefited more from philanthropy, those who received it or those who gave?

His question came in the form of criticism of a national commission on private philanthropy proposed by John D. Rockefeller III and led by John H. Filer, the president of the Aetna Life & Casualty Company.

The group, made up of government officials and business leaders, was formed to study the impact of tax and regulatory changes that could affect philanthropy. But mr. Eisenberg argued that the committee, and the philanthropic world at large, ignored the needs of the public, was not representative, and was not accountable, accessible, and fair.

“You can’t say you have a serious priority for poor people unless you’re willing to fund them,” he recalled in a 1998 interview with Shelterforce, an online community development publication.

His challenges to funding the foundation were initially rejected, but later embraced by Mr. Filer and other enlightened philanthropists, who helped create the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, a watchdog group, with him.

While many charities remained insular, others responded to Mr. Eisenberg’s urging by directing more donations to community organizations and diversifying their boards by including representatives from those organizations.

“I saw him berate the presidents of the foundation for failing to invest in grassroots organization, for neglecting racial justice, for not giving groups mainstream support and long-term funding, and for being inaccessible and haughty,” he said. Deepak Bhargava, a former president of Community Change (originally called the Center for Community Change), wrote in a tribute to Mr. Eisenberg. And, he added, “He argued that we should do more to engage the middle class and centrist forces in the fight against poverty.”

Mr. Bhargava confirmed Mr. Eisenberg’s death at a nursing home in Rockville, Md.

“I believe in empowerment, as I think almost everyone does,” Mr. Eisenberg told The Los Angeles Times in 1986. “The goal of empowerment and self-help is not to guarantee that everyone will succeed, but to provide equal opportunities for everyone.”

Pablo Samuel Eisenberg was born in Paris on July 1, 1932, to an American Jewish couple who had lived in Europe since the early 1920s: Maurice Eisenberg, a cellist, and Paula (Halpert) Eisenberg, a housewife.

A few weeks after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the family sailed to the United States and settled in Maplewood, NJ, where Pablo — who was named after his godfather, the cellist Pablo Casals — attended Millburn High School.

He received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Princeton University in 1954 and a Bachelor of Letters degree from Merton College at the University of Oxford in 1957.

He also wanted to play the cello, but he chose a different stringed instrument: he captained the Princeton and Merton tennis teams, and established himself as a star on the tennis circuit.

Mr. Eisenberg played five times at Wimbledon and reached the quarterfinals with John Ager in 1955. He won a gold medal at the 1953 Maccabiah Games in Israel and in 1954 was ninth in the United States doubles.

After college, he served in the military for two years before joining the US Information Agency in Senegal for three years. He then served as program director for Operation Crossroads Africa, a predecessor of the Peace Corps, for two years. He later served as director of Pennsylvania operations for the federal Office of Economic Opportunity and deputy director of the Washington Department of Research and Development. He then entered the non-profit sector and became deputy director of field operations for the National Urban Coalition.

He also chaired Friends of VISTA, a non-profit organization that supports the federal agency for community service and volunteerism.

Mr. Eisenberg was a columnist for The Chronicle of Philanthropy and author of the book “Challenges for Nonprofits and Philanthropy: The Courage to Change” (2004). After working at Community Change, he became a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute at Georgetown University.

His wife of 62 years, Helen (Cierniak) Eisenberg, died this year. He is survived by their daughter, Marina Eisenberg, and a sister, Maruta Friedler.

“Pablo Eisenberg was a staunch defender of civic values across the board,” William Josephson, a former assistant attorney general in charge of the New York State Department of Law’s Charities Bureau, said in an interview. “He nurtured civil rights and poverty leaders and provided homes for fragile organizations.”