Getty Images

On Tuesday, Microsoft detailed an ongoing large-scale phishing campaign that can hijack user accounts when protected with multi-factor authentication measures designed to prevent such takeovers. The threat actors behind the operation, which have targeted 10,000 organizations since September, have used their secret access to victims’ email accounts to trick employees into sending the hackers money.

Multi-factor authentication, also known as two-factor authentication, MFA or 2FA, is the gold standard for account security. It requires the account user to prove their identity in the form of something they own or control (a physical security key, a fingerprint, or facial or retina scan) in addition to something they know (their password). As the increasing use of MFA has hindered account takeover campaigns, attackers have found ways to retaliate.

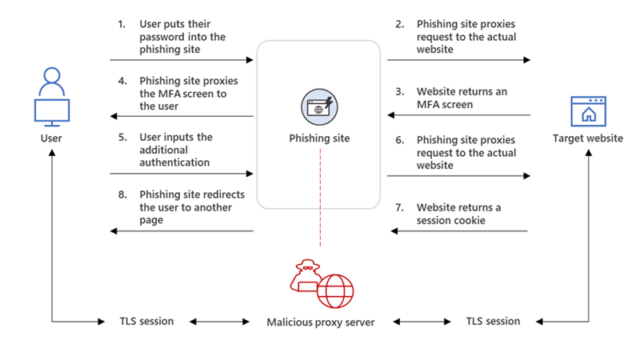

The opponent in the middle

Microsoft observed a campaign that inserted an attacker-controlled proxy site between the account users and the work server they were trying to log into. When the user entered a password on the proxy site, the proxy site sent it to the real server and sent the response from the real server back to the user. After the authentication was completed, the threat actor stole the session cookie that the legitimate site sent so that the user does not have to re-authenticate with each new page visited. The campaign started with a phishing email with an HTML attachment that led to the proxy server.

“Our observation shows that after a compromised account was logged in to the phishing site for the first time, the attacker used the stolen session cookie to authenticate to Outlook online (outlook.office.com),” members of the Microsoft 365 Defender Research Team and the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center wrote in a blog post. “In multiple cases, the cookies had an MFA claim, meaning that even if the organization had an MFA policy, the attacker used the session cookie to gain access on behalf of the compromised account.”

In the days following the cookie theft, the threat actors accessed employee email accounts and searched for messages to use in corporate email scams that tricked targets into transferring large sums of money to accounts they believed to be they belonged to colleagues or business partners. The attackers used those email threads and the hacked employee’s forged identity to convince the other party to make a payment.

To prevent the hacked employee from discovering the compromise, the threat actors created inbox rules that automatically moved specific emails to an archive folder and marked them as read. Over the next few days, the threat actor logged in regularly to check for new emails.

“On one occasion, the attacker made multiple fraud attempts simultaneously from the same compromised mailbox,” the blog authors wrote. “Every time the attacker found a new fraud target, they updated the inbox rule they created to include the organizational domains of these new targets.”

Microsoft

It’s so easy to fall for scams

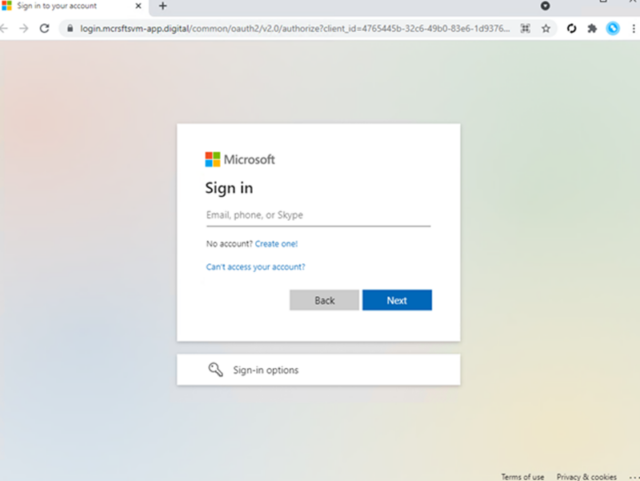

The blog post shows how easy it can be for employees to fall for such scams. The sheer volume of emails and the workload often make it difficult to know if a message is authentic. The use of MFA already indicates that the user or organization applies good safety hygiene. One of the few visually suspicious elements in the scam is the domain name used on the proxy site’s landing page. But given the opacity of most organization-specific login pages, even the sketchy domain name might not be a dead giveaway.

Microsoft

Nothing in Microsoft’s account should be construed to mean that deploying MFA is not one of the most effective measures to prevent account takeovers. That said, not all MFA is created equal. One-time authentication codes, even when sent by text, are much better than nothing, but they remain phishable or interceptable through more exotic abuses of the SS7 protocol used to send text messages.

The most effective forms of MFA available are those that meet the standards set by the industry-wide FIDO Alliance. This kind of MFA uses a physical security key that can be provided as a dongle by companies like Yubico or Feitian or even an Android or iOS device. The authentication can also come from a fingerprint or retina scan, neither of which leaves the end user’s device to prevent the biometric data from being stolen. What all FIDO-compliant MFA have in common is that it cannot be phishing and uses back-end systems that can withstand these types of ongoing campaigns.