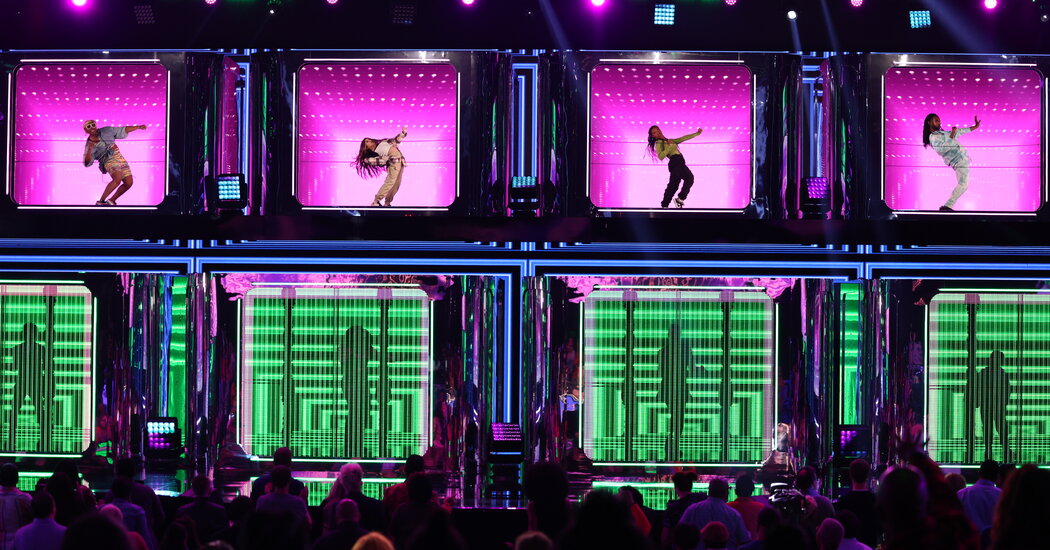

Even by the dazzling standards of TV talent competitions, “Dancing With Myself” sets an impressive scene. Two stacked rows of room-sized cubes, trimmed with glittering lights, fill the stage – ‘Hollywood Squares’ meets ‘Saturday Night Fever’. At the jury table are pop stars Shakira and Nick Jonas and internet celebrity Liza Koshy; behind them a cheering studio audience. The door of a cube slides open to reveal the show’s first contestant, who begins to perform…

… a TikTok-style dance challenge. The kind creators on the app are known for filming in their bedrooms, pajamas optional.

The artificial glamor of network reality TV may seem at odds with the carefree looseness of TikTok dance. “Dancing With Myself” aims to prove otherwise. The new NBC show, from Tuesday through July 19, attempts to translate the viral dance challenge phenomenon into a reality competition format.

The packaging is familiar: an elaborate set, a live audience, a collection of famous judges. But the program participants who can easily participate via social media – who perform short dance challenges in isolated ‘pods’ – don’t look and move like most dance show participants. And the judges don’t just comment from behind the table: they’re also seen as creators, setting and teaching the show’s dance routines.

“Dancing With Myself” taps into the current power of TikTok and the now vaguely nostalgic power of a network television talent show. In its efforts to marry these two cultures, it has faced some of the same issues that have taken the social media world by storm — revealing just how much TikTok dance itself has evolved.

“It tries to legitimize TikTok dance in a venue that is the antithesis of TikTok,” said Trevor Boffone, a teacher and author of the book “Renegades: Digital Dance Cultures from Dubsmash to TikTok.” “But it also shows how deeply this type of dance is embedded in popular culture.”

“Dancing With Myself” entered development in early 2021, just after the dance challenge had reached its peak. “We saw people having these virtual dance parties and posting these dances from their living rooms, with everyone looking for a way to connect,” said executive producer John Irwin. “And we thought, ‘My god, there must be a show in this.'”

The power of celebrities made the idea clear. In December 2020, Shakira and the Black Eyed Peas released the dance-forward music video for their song “Girl Like Me”. It quickly went viral as fans tried to recreate a jazzercise-inflected passage of the choreography, which was co-created by Maite Marcos, Shakira, Marc Tore and Sadeck Waff.† Already a veteran of dance challenges, Shakira started reposting her favorite ‘Girl Like Me’ videos on her social accounts. “She felt like the perfect person to go with this,” Irwin said.

Shakira came on board as an executive producer and as the judges leader of the show. Later, model Camille Kostek joined as host, and Koshy and Jonas rounded out the jury.

You will never hear the name TikTok on “Dancing With Myself”. (“We didn’t want to be ‘the TikTok show,’ because we thought this movement was bigger than that,” Irwin said.) But the TikTok culture, which emerged for television, shapes many aspects of the format.

Each episode’s 12 contestants learn a series of routines that resemble social media dance challenges in their brevity and relative simplicity. They perform in square “pods” suggesting the secluded seclusion of phone screens, which can’t see each other for most challenges. Like many TikTok dance makers, Jonas, Koshy, Kostek and Shakira are not experienced choreographers, but they all demonstrate and help them learn the routines of the show. While judges have the option to save favorite dancers, “likes” are the currency of the competition, with winners being determined by audience votes animated on screen like a shower of hearts.

Perhaps the ‘Dancing With Myself’ approach to casting is most in line with TikTok’s ethos. “What leads to success in the app isn’t necessarily good dancing, but really the artist’s personality,” Boffone said.

While some “Dancing With Myself” contestants are gifted and highly trained dancers, the show makes a point of including charismatic contestants of all skill levels. Many are already notable features of TikTok: the dancing flight attendant, the dancing police officer, the dancing dentist. (And the dancing TikTok scholar. Boffone, who posts routines with his students on Instagram and TikTok, was cast as an alternate for the show’s fifth episode.)

“This is a show that’s for everyone,” Shakira said in an email. “It’s about celebrating the love of dance and personal stories in all people, not just professionals.”

“Dancing With Myself” has arrived as TikTok dance hits an inflection point. In 2019 and early 2020, when the platform was still mostly known as the ‘teendance app’, the culture revolved around the dance challenge. But as TikTok has expanded to a wider range of users and applications, dance challenges have become less dominant. The Renegade Challenge, which Jalaiah Harmon choreographed in the fall of 2019, has 124.8 million views. This spring’s blockbuster dance, choreographed by Jaeden Gomez to Lizzo’s song “About Damn Time,” has about 31 million views.

Continued questions about proper recognition of dance makers, especially makers of color, have also helped cool the trend of dance challenges. During last summer’s #BlackTikTokStrike campaign, some black performers, frustrated by white influencers co-opting their dance content, took a step back from the platform. (The app recently added a built-in credit feature that allows users to identify the original creator of a dance.)

The show’s relationship to this conversation is somewhat complicated. “Dancing With Myself” doesn’t include the participants’ social media handles or even their last name, making it difficult to find or follow them online. It also, in a way, replicates some of the credit problems that many TikTok creators have protested against. During the show, the celebrities are identified as creators of the dance challenges and demonstrate the choreography as if it were their own. Behind the scenes, they are joined by a team of professional choreographers – Brittany Cherry, Cameron Lee, Will Simmons and Kelly Sweeney – themselves chosen by the married choreographers and co-executive producers Tabitha and Napoleon Dumo.

“If you’re not a choreographer, it’s quite a to-do to create so many dances in a short period of time,” says Napoleon, who has worked with Tabitha on “So You Think You Can Dance” and “Dancing With the Stars”. among other shows. “We are there to assist the makers in the choreography. We lay a foundation together, and then we work with them on what feels right and which moves they want to put in the dance.”

Napoleon notes that the show’s ending titles include all of the choreographers’ names, which is already more esteemed than some television dancers. “To put that information in the episode itself, I think it would be confusing for the audience,” he said. “We don’t always say when Tom Cruise is doing a stunt or when it’s a stuntman.”

The entry list of “Dancing With Myself” includes several successful social media stars. Why would they submit to the reality TV meat grinder? Because the sheer number of followers of popular creators can obscure the narrowness of their fame, which is often limited to an online niche group. A national TV show offers greater limelight – a boon to those seeking greater recognition for their work.

“I mean, it’s… network‘ said Marie Moring, a contestant on the second episode who has nearly 700,000 TikTok followers. “Social media is pretty new, but NBC already exists. People know NBC.” And Moring, 46, found that the show helped her reach a new demographic: her peers. “A lot of Gen Xers, my people, they’re not on social media, but they watch TV,” she said. “People are now coming to my page to say they’ve seen me on the show.”

TikTok fame is also limited by the platform’s short video format, which allows only a brief glimpse of the creators. Keara Wilson, 21, the winner of the second episode of “Dancing With Myself”, is one of the most famous TikTokers to appear on the show: she choreographed the Savage Challenge that swept the internet in Spring 2020 and now has 3, 4 million followers. Despite her viral moment, Wilson said she thought few of her fans knew much about her.

“There’s just not much you can show with 15 or 30 second videos,” she said. Her choreography was an odd semi-fame — made all the more complicated by the appropriation of her choreography by white creators, meaning that many who encountered the Savage Challenge never knew Wilson had made it. (Wilson is now in the process of copyrighting her Savage dance.)

But reality TV is the realm of the backstory, and “Dancing With Myself” includes packs showing the participants’ offline and online lives. During the show, the judges not only named Wilson as the creator of the Savage Challenge, but also revealed to viewers about her upcoming wedding and her extensive dance experience outside of TikTok Challenges. “It’s been two years,” Wilson said during her episode, “and I can finally show who I really am.”

Neither Moring nor Wilson saw a significant bump in their TikTok following after appearing on “Dancing With Myself”. However, both said they forge valuable connections with many of the creators they met on the show. Boffone described the hotel the contestants stayed in during filming as “TikTok Summer Camp,” with everyone staying up late dancing and sharing career advice.

“A lot of us were really excited to be around other people who get it,” he said. “It’s like, hey, how do I talk to brands? What are some good strategies for using hashtags? It’s become a cohort of people all sharing resources and helping each other be successful.”

While “Dancing With Myself” is far from a runaway hit, it may reflect the next step in the evolution of TikTok-esque dance: the dance challenge going offline. As the app’s vocabulary and memes have seeped into mainstream culture, TikTok dances have taken off everywhere from concerts to baseball games. There may be a day when you’re less likely to see TikTok dancing on TikTok than on TV.

“These kinds of moves, it’s not the platforms that create them, it’s the people,” Irwin said. “We’re providing another place for that movement to spread.”