The Perseverance rover landed in the Jezero crater on Mars, largely because of extensive evidence that the crater once hosted a lake, meaning liquid water that once hosted life on Mars. And the landing was a success, placing the rover on the edge of a structure resembling a river delta where the nearby highlands emptied into the crater.

But a summary of the rover’s first year of data, published in three different papers released today, suggests that Perseverance has yet to find any evidence of a water paradise. Instead, all evidence indicates that exposure to water in the areas studied was limited and that the waters were likely near freezing. While this doesn’t rule out finding lake deposits later on, the environment may not have been as inviting to life as “a lake in a crater” might have suggested.

Put everything together

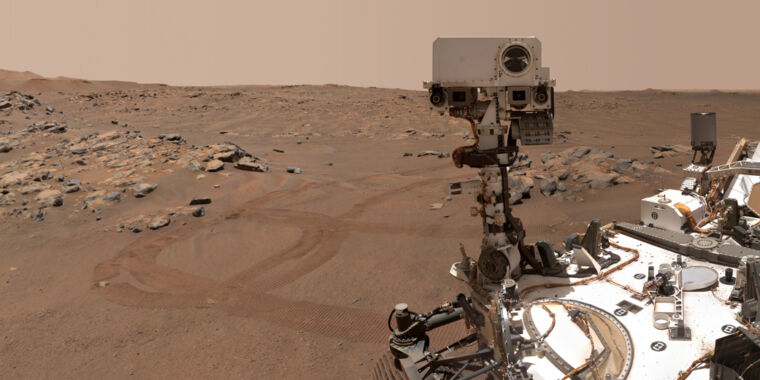

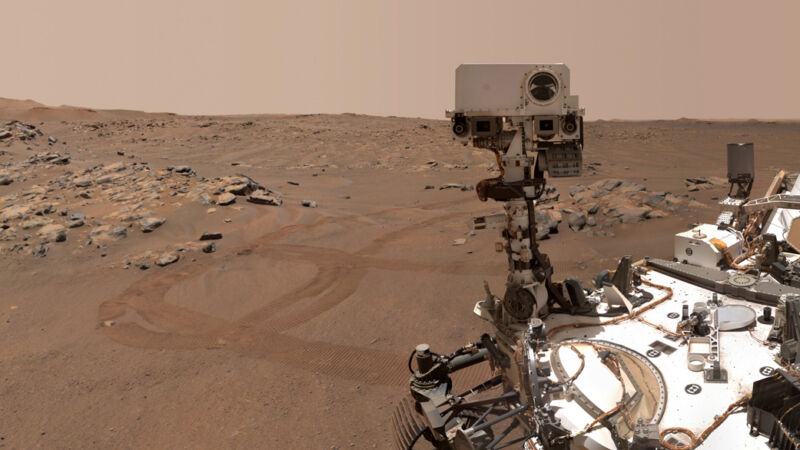

Perseverance can be thought of as a platform for a large array of instruments that provide a view of what the rover is looking at. Even its “eyes,” a pair of cameras mounted on its mast, can create stereo images with 3D information and provide information about what wavelengths are present in the images. It also has instruments that can be held against rocks to determine their contents and structure; sample handling hardware can perform chemical analysis of materials extracted from rocks.

While the new information is divided into separate documents based on the tools the data comes from, the important thing is that all three paint a consistent picture and build on each other.

For example, the spectroscopy tools detail the chemical composition of a sample, but they don’t tell us how those chemicals are distributed in a rock. In contrast, there are X-ray analysis tools that provide imprecise chemical information, but they tell us how the chemicals that are being detected are compared to the visible features of the rock. And the cameras on the rover’s mast could help us determine how widespread similar rocks are.

Collectively, these tools tell us that Perseverance has so far sampled rocks from two different deposits. The first includes the crater floor where it landed, which is rich in iron and magnesium based minerals. Above that is a separate formation that resembles volcanic rock, although we cannot rule out the possibility that it was formed by rock that liquefied after an impact.

Both deposits are clearly formed by processes that we know take place on Mars. Many of the rocks were formed by the wind and may have undergone some chemical changes due to the atmosphere or exposure to radiation. Loose regolith has built up in places shaded by the wind, much of it with the distinctive red hue of Mars. There is also a variety of debris from impacts, including some smaller ones in the Jezero crater.

But the big question is whether the materials show evidence that water was present. The answer there is kind of “yes, but…”