The National Enquirer’s long-standing practice of “catch and kill” — buying and then burying unsavory stories about powerful people — is at the center of the criminal prosecution of former President Donald J. Trump in New York.

But the tabloid’s new publisher says hush money is no longer part of the Enquirer’s business.

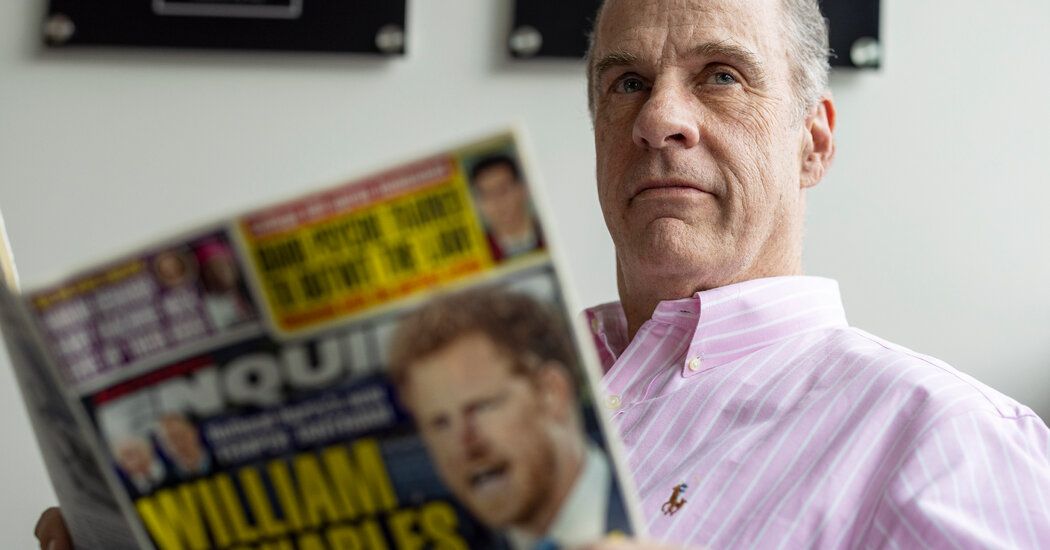

“Look, it’s a new day,” said Ted Farnsworth, an entrepreneur whose firm Icon Publishing was part of a group that bought the National Enquirer in February. “I don’t even understand how ‘catch and kill’ works because I’m not from publishing, but I just know I don’t want it around.”

During an hour-long interview, Mr. Farnsworth, 60, distanced the tabloid from the tactics employed by the Enquirer’s previous leadership. He said David Pecker, the former publisher of the tabloid and a key player in the hush money scheme laid out by prosecutors this week, is no longer involved in day-to-day operations. The tabloid still pays for stories, he said, but tipsters aren’t paid until their information is published — a practice designed to reveal rather than hide information.

Mr Farnsworth said he was focusing on mining the Enquirer’s nearly 100-year-old archives for stories that could be turned into new TV shows, films and podcasts. And he said the publication’s coverage would focus less on politics and more on celebrity stories.

“From the vaults of The National Enquirer, did Elvis really die in the mansion or did he die in a hotel in Mississippi?” said Mr Farnsworth.

“Inquiring minds want to know,” he added, referring to the publication’s decades-old slogan.

In the indictment against Mr. Trump that was unsealed Tuesday, prosecutors said the former president falsified company records related to hush money payments to avoid negative press during the 2016 campaign. Mr. Pecker played a role in each of the payments made to the three individuals named by prosecutors.

Mr Farnsworth said he did not think the recent whirlwind of stories about Mr Trump and the tabloid would negatively impact the company’s business. The National Enquirer is not legally responsible for actions taken before the tabloid was purchased this year, he said.

This is the first attempt at publishing for Mr. Farnsworth, who is perhaps best known for funding MoviePass, the failed subscription service that allowed customers to see a movie in theaters every day. The company exploded in popularity before the pandemic, drawing millions of users — and at one point losing $20 million a month — before going out of business.

Last year, the Justice Department accused Mr Farnsworth of defrauding MoviePass investors, saying he made misrepresentations that artificially inflated the price of the parent company’s shares. Mr Farnsworth has pleaded not guilty and declined to comment on the matter in the interview.

Mr. Farnsworth said Icon Publishing and another investor, Vinco Ventures, paid less than $100 million for the Enquirer. Last year, he said, the publication generated about $13.5 million in revenue before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or EBITDA. He said the publishing industry’s hand-wringing about the extinction of print publishing doesn’t square with the reality at the Enquirer, which continues to be popular with readers at newsstands and in stores including Walmart and Dollar General.

“You always hear ‘print is dead, print is dead’,” said Mr Farnsworth. “Print is not dead.”

But he’s also trying to expand the publication’s digital business. The Enquirer’s website hasn’t been updated with news for a year, which Mr Farnsworth attributed to a long-running digital revamp that he says will be completed soon. Mr Farnsworth said he also pursued strategies designed to capitalize on the Enquirer’s ubiquitous supermarket shelves, including giving away a new Corvette through the print newspaper using a scannable “QR” code.

The shift away from political coverage is a major break from the history of the National Enquirer, where campaign coverage has been a mainstay.

That coverage has led to caution among presidential candidates. In 2016, Mr. Trump and his then-lawyer Michael Cohen discussed a plan to purchase a cache of sensitive information collected by National Enquirer journalists about Mr. Trump. That plan failed to result in a deal, and Mr. Farnsworth said he received no damaging information about Mr. Trump when an 18-wheeler delivered boxes of the Enquirer’s archived records to the tabloid’s Syracuse studios this year.

That strategy of defeating politics also extends to the case against Mr. Trump. While the courtroom in Manhattan was packed with reporters for Mr Trump’s indictment on Tuesday, Mr Farnsworth said The National Enquirer planned to turn day-to-day coverage of the story over to other publications.