New York Governor Kathy Hochul passed the Digital Fair Repair Act into law, months after it passed both chambers of the state legislature by overwhelming bipartisan majorities. The bill was originally approved in June but was not formally sent to Hochul’s office until earlier this month; the governor had until midnight on December 28 to sign the bill, veto it, or pass it into law without her signature.

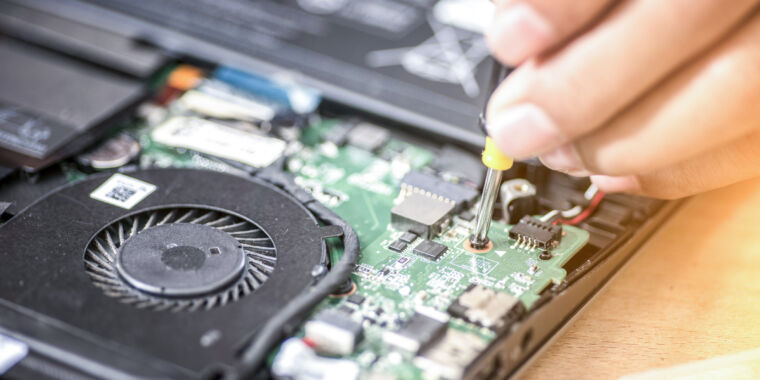

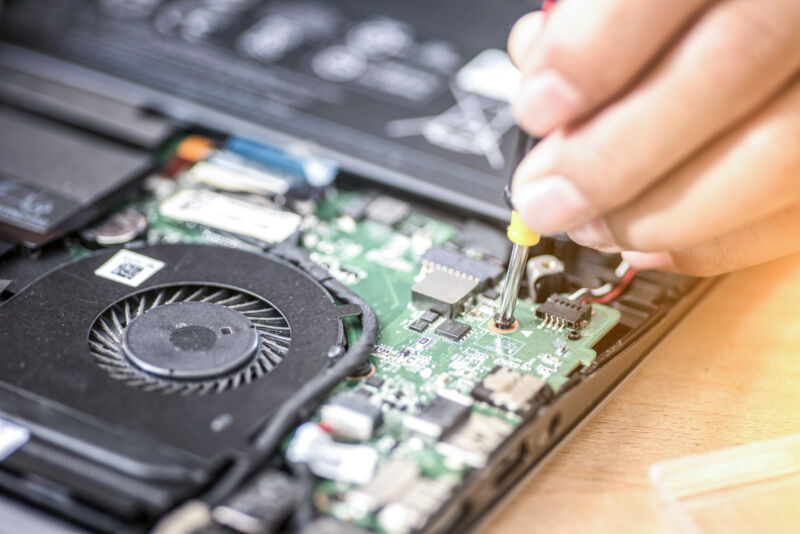

The Digital Fair Repair Act is the nation’s first right-to-repair bill passed by a state legislature (rather than being implemented via an executive order), and has been hailed as “precedent-setting” by right-to-repair advocates groups like iFixit. The law requires companies to provide the same diagnostic tools, repair manuals and parts to the public as they do to their own repairers.

But tech industry lobbyists and trade groups like TechNet had already tried to water down the law when it passed state legislatures, and the bill as signed by Hochul contains even more conditions and exceptions, ostensibly added to the concerns of the public. to take away the governor on “technical difficulties”. issues that could compromise safety and security, and increase the risk of injury from physical repair projects.”

“I am pleased to have reached an agreement with the legislature to address these issues,” Hochul wrote.

Most notably, only devices manufactured and sold in New York on or after July 1, 2023 must meet the regulatory requirements, with the exception of all currently existing products – those that people already own and may want to use at some point. want to repair moment over time. line. Business-to-business and business-to-government equipment not sold to consumers is also excluded. And manufacturers don’t have to provide passwords or other tools to get around device security lockouts — on balance, probably good for anti-theft features Apple and other manufacturers provide for stolen phones, but bad for people who are locked out of their own otherwise functional devices because they have a password. have been forgotten or cannot find a recovery key.

Manufacturers may also choose to provide “assemblies” of parts rather than parts themselves “when the risk of incorrect installation increases the risk of injury”. For example, if you want to replace your phone’s screen or battery, a company can provide you with a screen or battery with a bunch of extra cables or other parts attached to it, whether you need those parts or not. This can drive up the cost of repairs, reducing their appeal.

These compromises are stacked on top of some broad exemptions already in the original bill, which exclude medical devices, motor vehicles, outdoor equipment or household appliances.

Right-to-repair activists praised the passage of the bill while acknowledging that the compromises make it weaker than it should be.

“This is a huge win for consumers and a major step forward for the right to fix motion,” wrote Kyle Wiens, CEO of iFixit. “New York has set a precedent for other states to follow, and I hope more states will pass similar legislation in the near future.”

“The reparation law that I spent seven years of my life trying to get in my home state has failed,” activist Louis Rossmann said in a video explaining Hochul’s changes to the law. “And it’s funny, it got fucked exactly the way I thought it would…Because it got passed without getting infected or screwed up would actually be good for society, and that’s not something that [the] The New York State government will allow it to happen.”