NASA/JPL-Caltech

During his final months as chief of NASA’s science programs last year, there was one mission that worried Thomas Zurbuchen more than any other: the agency’s ambitious plan to return rocks from Mars to Earth. He supported the Mars Sample Return mission and helped get it through the agency approval process. But the project threatened to eat up the agency’s science budget.

“This was the thing that gave me sleepless nights towards the end of my tenure at NASA and even after I left,” said Zurbuchen, who left NASA after seven years in charge of the science missions directorate in late 2022. “I think that there is a crisis going on.”

Now, Ars has learned, the problem may be even worse than Zurbuchen imagined.

According to two sources familiar with the meeting, mission program manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Richard Cook, and mission director at NASA Headquarters, Jeff Gramling, briefed agency leaders last week on the cost. They had sobering news: the price had doubled. Development costs for the mission were no longer $4.4 billion. Rather, the new estimate put it at $8 to $9 billion.

In addition, this only represents the cost to build and test the various components of the mission. It does not include launch costs, operational costs over five years, nor the construction of a new sample reception facility to process the rocks and soil of Mars. All told, the total cost of the Mars Sample Return mission is now about $10 billion.

About the mission

NASA and its international partners, including the European Space Agency, have wanted to return material from Mars for decades. It is also a top priority of the scientific community, both to better understand the geological history of Mars and to search for evidence of life – past or present – on Mars.

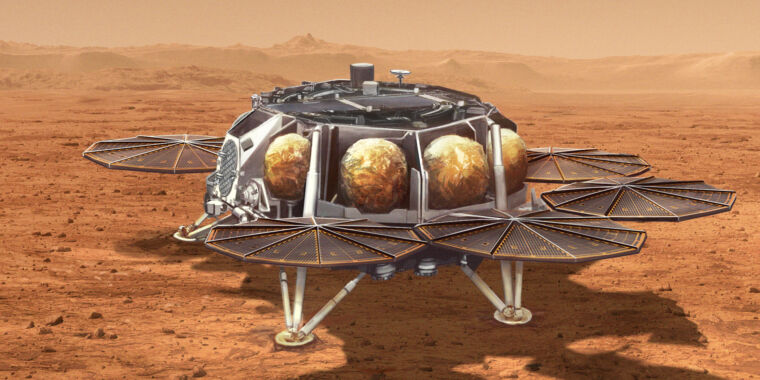

After several iterations, NASA and its European partners made a decision last summer on the project’s current design. Under this plan, NASA will develop a large “Sample Retriever Lander” nominally due for launch in 2028. After this vehicle lands on Mars, the Perseverance rover – which has collected and stored samples of Martian dust in 38 titanium tubes, each the size of a large hot dog – will deliver its samples to the lander.

However, perseverance can be a bit long in the tooth by the time the lander arrives. Because Perseverance landed on Mars in 2021, NASA has decided that it is too risky to fully count on the rover being operational in ten years. Accordingly, it plans to send two helicopters, similar to Ingenuity, which remains operational on Mars, as a backup plan to retrieve the samples.

Once delivered to the lander, these sample tubes are placed aboard a rocket called the Mars Ascent Vehicle. This missile is being developed by Lockheed Martin and will be stored in the lander. After launching from Mars, this rocket will carry the Orbiting Sample container into Mars orbit, where it would be picked up by an Earth return orbiter built by the European Space Agency. This vehicle would return the monsters to orbit, where they would be released into a small spacecraft to land on the planet. NASA made a video showing how this could work.

If NASA succeeds in developing and launching the Sample Retriever Lander by 2028, the samples could be returned to Earth in 2033. The problem is that no one expects the lander to launch in 2028. At the moment, even 2030 seems like an ambitious goal.

Mistakes have been made

There is already a background rumor in the scientific community about cost overruns for this mission. After the space agency received $822 million in this year’s federal budget for Mars Sample Return, it is asking for $949 million in fiscal year 2024. This is well above the level of credit that even the agency’s most expensive science mission, the James Webb Space Telescope, pursued on an annual basis. In addition, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson warned in April of near-term cost growth in the mission.

Around the same time, NASA convened an “Institutional Review Board” to review the agency’s strategy for the mission and make recommendations for its success. The board is led by Orlando Figueroa, a retired deputy center director for science and technology at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and the group will release a report in late August.

So what happened to drive up these costs?

Zurbuchen said “horrific” engineering mistakes were made during the early planning stages at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The original concept involved sending everything on a single lander, including a small rover to “get” Perseverance’s monsters. However, the depth of this analysis was insufficient and contained large errors about landing leg mass and other factors. For a while, the plan had to evolve to add a second lander, which increased costs by more than $1 billion.

In addition, the planning for Mars Sample Return was bogged down by the management issues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, including staffing issues that led to the delay of the Psyche mission. An independent investigation found that the California-based field center, which directs many of the space agency’s most prestigious science missions, had taken on an “unprecedented workload” without having the resources needed to complete major projects.

Now it’s on its biggest mission yet in Mars Sample Return.