Earlier this summer, it briefly looked like NASA's prime mission to study Jupiter's icy moon Europa might miss its launch date this year.

In May, engineers raised concerns that transistors installed throughout the spacecraft could be susceptible to radiation damage, a ubiquitous threat to any probe flying around Jupiter. The transistors are embedded in the spacecraft’s circuitry and are responsible for about 200 unique applications, many of which are critical to keeping the mission running as it orbits Jupiter and repeatedly zooms past Europa, interrogating the frozen moon with nine scientific instruments.

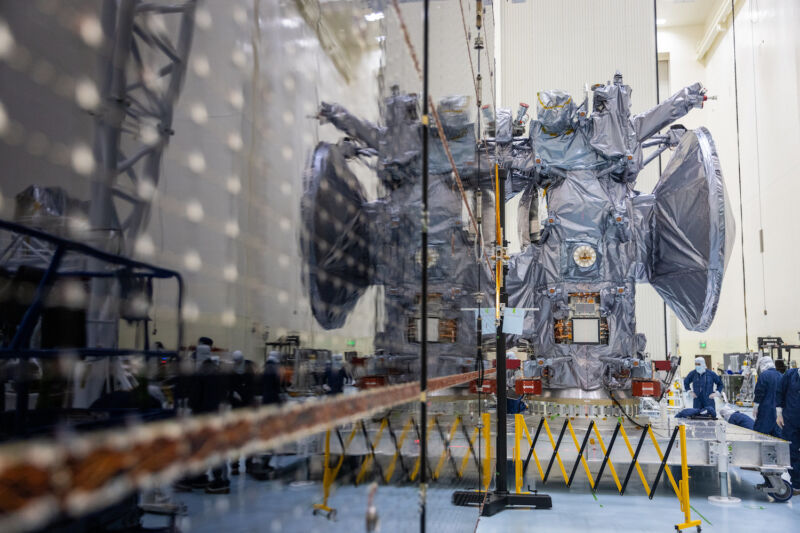

The transistors on the Europa Clipper spacecraft have already been installed, and removing them for inspection or replacement would delay the mission's launch until late next year. Europa Clipper has a 21-day launch window, beginning Oct. 10, to begin its journey to the outer solar system.

After testing similar transistors on the ground for four months, engineers concluded that the transistors on Europa Clipper could withstand the extreme radiation the spacecraft would encounter around Jupiter without requiring any changes to the mission's flight plan or route.

“A major challenge was analyzing how those transistors on the spacecraft would handle the radiation environment on Jupiter,” said Jordan Evans, Europa Clipper project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “After extensive testing and analysis of the transistors, the Europa Clipper project and I personally are confident that we can complete the original mission to explore Europa as planned.”

Senior NASA officials decided Monday that they agreed with the assessment of the Europa Clipper team at JPL.

“It's great to be here with some incredibly good news,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate. “We're all extremely excited here. Hot off the presses, we've just put the Europa Clipper mission through a major milestone review … the last major review before we really get into that launch fever, and we're very pleased to say that they passed that review today unequivocally.”

With approval from NASA headquarters, teams preparing Europa Clipper for launch at Kennedy Space Center in Florida later this week will begin loading about 3 metric tons (6,600 pounds) of fuel into the spacecraft. That’s about half the total weight of the Europa Clipper spacecraft, the largest probe NASA has ever built for planetary exploration. NASA and SpaceX engineers will then pack the probe into the launch vehicle and connect it to a Falcon Heavy rocket for liftoff next month.

“I am pleased to say that we are confident that our beautiful spacecraft and our capable team are ready for launch, operations and our full science mission on Europa,” said Laurie Leshin, center director at JPL.

This is an awesome mission

After lifting off from Florida’s Space Coast next month, Europa Clipper will reach Mars in February 2025 for a gravity-assist flyby to gain speed on its journey to Jupiter. A subsequent flyby of Earth in December 2026 will bend Europa Clipper’s path to intercept Jupiter’s orbit in April 2030, when the probe will fire its engine to slow itself for capture by the giant planet’s immense gravitational field.

Then, Europa Clipper will set itself on a trajectory to fly by Europa 49 times over about four years, coming within 25 kilometers (16 miles) of the moon's icy surface. The instruments aboard Europa Clipper will map most of the moon's icy crust and look for signs that Europa's subsurface ocean of liquid water could be habitable for life. If scientists are lucky, the spacecraft might also fly through plumes erupting from Europa's surface, and these eruptions could contain pristine materials from the ocean beneath its icy shell. If that happens, Europa Clipper's instruments will get a taste of the chemistry of Europa's ocean.

“This is an epic mission,” said Curt Niebur, Europa Clipper program scientist at NASA Headquarters. “It's a chance for us to explore not a world that was habitable billions of years ago, but a world that could be habitable today, right now.”

Europa, about 90 percent the size of the moon, orbits Jupiter at the outer edge of the planet's radiation belts. Charged particles could disrupt the electronics of any spacecraft that dares to pass through the region.

The most sensitive electronics on Europa Clipper are mounted in a vault with walls of aluminum-zinc alloy to shield the components from Jupiter's radiation. Many of the spacecraft's transistors are in this vault, but others are built into science instruments on the outer edges of the spacecraft.

The transistors have a self-healing property known as annealing, which allows them to recover much of their capacity after exposure to intense radiation. For most of Europa Clipper’s orbit around Jupiter, the spacecraft will fly in a less damaging radiation environment, giving the transistors time to repair themselves between flybys of Europa, where radiation is at its worst. The only change mission managers on Europa Clipper will make will be to adjust the heating settings around some of the suspect transistors on two instruments outside the vault. Higher temperatures allow the components to repair themselves more efficiently.

“These are metal oxide field effect transistors, so you can think of them as electronic switches where you apply a voltage and then you can close an electronic switch,” Evans said.

““In some cases, the switch just goes on permanently, and if that switch turns on a little 1-watt decontamination heater, that's not a big deal for the mission,” Evans said. “But if that circuit is telling the spacecraft to go into safe mode, that's a little bit bigger deal. It's a much bigger deal. So we analyzed each of those circuits and looked at how robust and tolerant they are to degraded transistors, and we determined that we had enough margin in each of those circuits to confidently accomplish this flagship mission.”