At least one child has died of unexplained liver inflammation in a growing international outbreak of puzzling cases of childhood hepatitis, according to the World Health Organization.

The number of outbreaks has reached more than 170 cases in 12 countries and is expected to continue to grow. At least 17 children — 10 percent of cases — have required a liver transplant. The ages of the affected children range from one month to 16 years, although the majority are children under 10 years of age and many under 5 years of age.

Over the weekend, the WHO reported 114 cases in the UK, 13 in Spain, 12 in Israel, six in Denmark, less than five in Ireland, four in the Netherlands, four in Italy, two in Norway, two in France, one in Romania and one in Belgium. The WHO also noted nine cases in the US, all in Alabama. But last week, two more cases were reported in North Carolina, bringing the total for the US to at least 11. Two of the cases in the US resulted in transplants.

The WHO has not reported the age or nationality of the deceased child, but no deaths have been reported in the US.

medical mystery

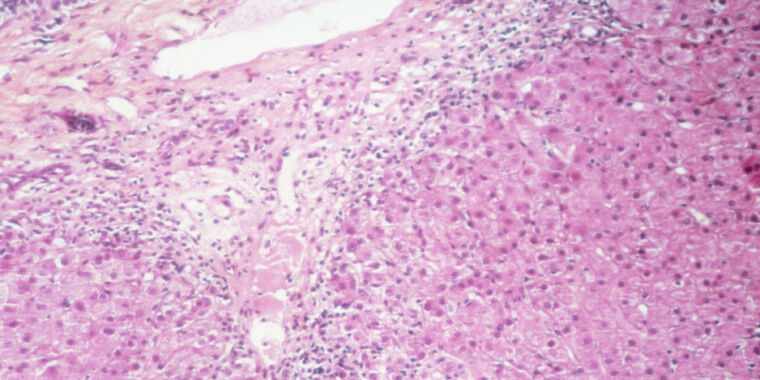

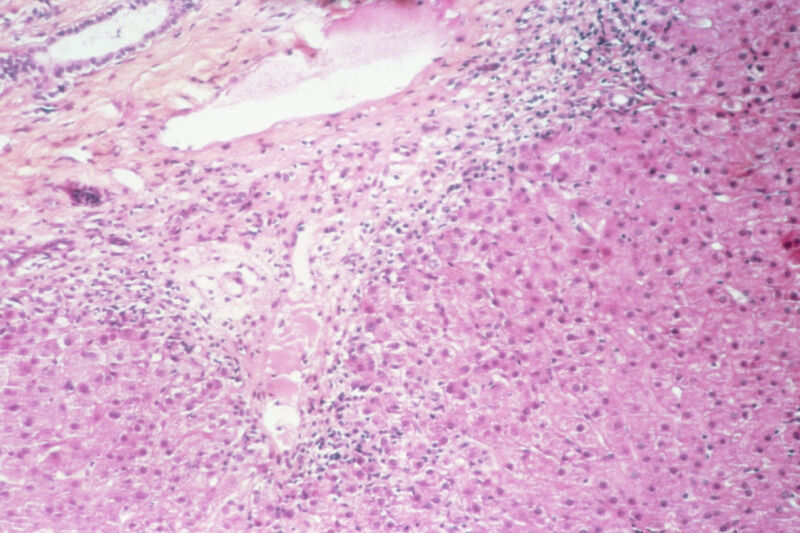

Although the worldwide number of cases seems low, severe liver inflammation (also known as hepatitis) is rare in young children. Health officials in Scotland – who first raised the alarm about the unexplained cases – realized something was amiss when they saw 13 cases of severe hepatitis in children in March and April. Typically, Scotland registers fewer than four such cases over an entire year.

Health experts around the world are trying to understand what causes the severe liver damage. Affected children have consistently tested negative for viruses that attack the liver, namely hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E. So far, there is no clear link between the cases, nor an association with travel, or a clear association with an exposure to the environment, drugs or food. The vast majority of cases had not received COVID-19 vaccines, ruling out that possibility.

The prime suspect remains an adenovirus, although the common family of viruses is not known to cause hepatitis in healthy children. Of the approximately 170 reported cases, at least 74 tested positive for an adenovirus, and 18 tested positive for adenovirus type 41 specifically.

More than 50 different adenoviruses are known to infect humans, but they are most commonly associated with respiratory, eye, and sometimes gastrointestinal and disseminated infections. Some adenoviruses have sometimes been associated with hepatitis, but generally only in immunocompromised children.

Adenovirus type 41, which has not been associated with hepatitis, typically causes diarrhea, vomiting, fever and respiratory symptoms, the WHO notes. Based on data from cases in the UK, the most common symptoms of the children affected by the outbreak are: jaundice, vomiting and abdominal painand most cases had no fever.

working hypotheses

The international outbreak comes as the UK and the Netherlands have documented an increase in adenovirus infections in the general community, driven by people returning to normal activities that had been restricted during the pandemic. As such, some experts have hypothesized that the cases of hepatitis may just be a rare outcome that has always been possible from a common adenovirus – but the rare outcome now seems to be more common because many immunologically naive children are simultaneously receiving adenoviruses after the pandemic. . Still, there is also the possibility that a new type of adenovirus has emerged that explains the cases of hepatitis.

It is also possible that it is not due to an adenovirus at all. Some data suggests that many children who have tested positive for an adenovirus have only low levels of the virus in their bodies. These data pointed to the possibility that the presence of adenoviruses is simply incidental – a reflection of the high transmission rate in the community, not the cause of hepatitis.

Furthermore, it is also possible that an adenovirus is only part of the story, and co-infection may explain the unusual cases. One possibility is that SARS-CoV-2 and an adenovirus co-infection is behind the cases. The WHO noted that 20 children tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and another 19 discovered a co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and adenovirus. But researchers also do not rule out the possibility that the liver damage is a rare consequence of an omicron infection alone or an infection with an as yet unidentified SARS-CoV-2 variant.

The WHO and other experts are calling for greater awareness, testing and global data sharing to unravel the mystery.