Benj Edwards / Flux

Growing up, if I wanted to experiment with something technical, my dad would take care of it. We had dozens of technical adventures together, but those adventures were cut short when he died of cancer in 2013. Thanks to a new AI image generator, it turns out my dad and I have one more adventure left.

Recently, an anonymous AI hobbyist discovered that a vision synthesis model called Flux can accurately reproduce a person’s handwriting if specially trained. I decided to experiment with the technique using written diaries left behind by my father. The results surprised me and raised deep questions about ethics, the authenticity of media artifacts, and the personal meaning behind handwriting itself.

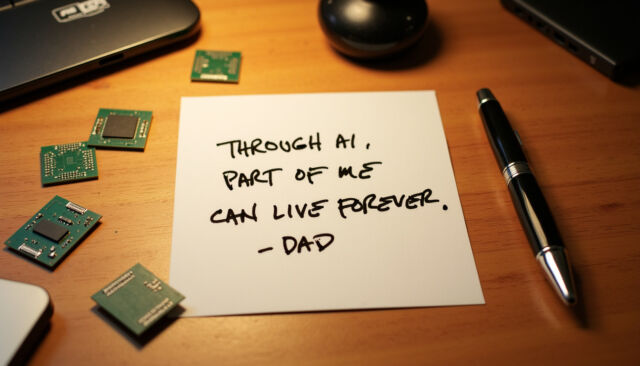

I’m also excited to see my father’s handwriting again. Captured by a neural network, a part of him will live on in a dynamic way that was impossible ten years ago. It’s been a while since he died, and I’m no longer grieving. From my perspective, this is a celebration of something wonderful about my father: resurrecting the unique way he wrote and what that conveys about who he was.

Benj Edwards / Flux

I admit that copying someone’s handwriting so convincingly can have its dangers. I’ve been warning for years about a coming era in which digital media creation and imitation are completely and effortlessly fluid, but it’s still wild to see something that feels like magic work for the first time. It’s tempting to say that we’re entering a new world in which all forms of media cannot be trusted, but in fact we’re seeing more evidence of what’s always been true: recorded media has no inherent veracity, and we’ve always judged the credibility of information based on the reputation of the messenger.

This fluidity in media creation is perfectly illustrated by Flux’s approach to handwriting synthesis. One of the most interesting things about the Flux solution is that the resulting handwriting is dynamic. For the most part, no two letters are rendered exactly the same. A neural network like the one powering Flux is a vast web of probabilities and approximations, so the imperfect flow of handwriting is an ideal match. What’s more, unlike a word processor font, you can natively insert handwriting into AI-generated scenes like signs, cartoons, billboards, chalkboards, TV images, and more.

-

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” with the command: A pen and ink drawn tabby cat from a newspaper holding a large ring and showing a speech bubble above its head that reads, “Why shouldn't I keep him?”

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI-generated image featuring Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” with the prompt “muscled barbarian with weapons next to a CRT television, cinematic, 8K, studio lighting. Screen reads 'ARS TECHNICA.'”

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” with the command “a photo of a large, colorful billboard along a highway that reads: 'THIS IS A PRETTY BIG SIGN'”

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” featuring my favorite store, Dadio Shack.

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI generated image using Flux and 'Dad's Uppercase' of a tattoo.

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” of a fictional cartoon family.

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” of a blackboard with fictional Pokémon stats.

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI-generated image featuring Flux and “Dad's Uppercase” with the prompt “a photo of a vintage green computer CRT screen glowing in the dark. An Apple II keyboard can be seen below the screen. On the screen, the graphics 'APPLE II FOREVER' glow in white”

Benj Edwards / Flux

-

An AI generated image using Flux and “Dad's Uppercase”.

Benj Edwards / Flux

It’s worth noting that neither I nor the guy who recently discovered that Flux can reproduce handwriting were the first to use neural networks to clone handwriting (the research has been going on for years). But it’s become almost trivially cheap to do this lately using a cloud service or consumer hardware if you have the handwriting on hand.

That's how I brought a part of my father back to life.

The discovery

As a daily tech news writer, I keep an eye on the latest innovations in AI image generation. Late last month, while browsing Reddit, I saw a post from an AI image hobbyist who goes by the name “fofr,” pronounced “Foffer,” he told me, so let’s call him that for convenience. Foffer announced that he had replicated JRR Tolkien’s handwriting using scans found in online archives.

Foffer initially made the Tolkien model available for others to use, but he voluntarily removed it two days later when he became concerned that people were misusing it to create handwriting in the style of J. R. R. Tolkien. But the handwriting cloning technique he had discovered was now public knowledge.

-

A screenshot of JRR Tolkien's original handwriting for LoRA, before the creator removed it in late August 2024.

Replicate

-

An AI-generated image created by a Redditor using Flux and a special model trained on JRR Tolkien's handwriting.

for / Flux

-

An AI-generated image, created using Flux and a special model trained on JRR Tolkien's handwriting.

for / Flux

-

An AI-generated image, created using Flux and a special model trained on JRR Tolkien's handwriting.

for / Flux

-

An AI-generated image, created using Flux and a special model trained on JRR Tolkien's handwriting.

for / Flux

-

An AI-generated image, created using Flux and a special model trained on JRR Tolkien's handwriting.

for / Flux