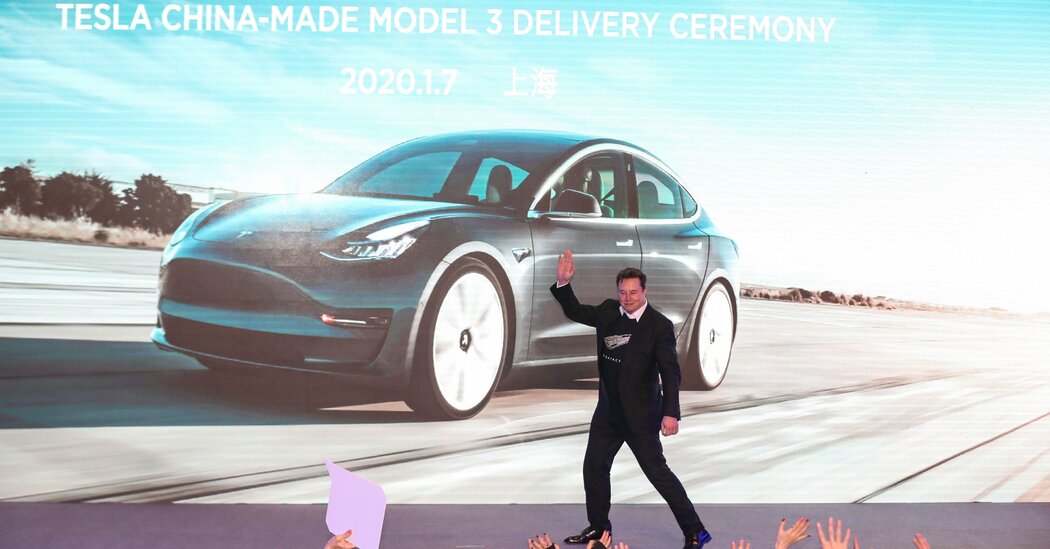

SAN FRANCISCO — When Elon Musk opened a Tesla factory in Shanghai in 2019, the Chinese government welcomed him with billions of dollars in cheap land, loans, tax breaks and subsidies. “I really think China is the future,” Mr Musk cheered.

Tesla’s path has been lucrative since then, with a quarter of the company’s 2021 revenue coming from China, but not without its problems. The company faced a consumer and regulatory uprising in China last year over manufacturing defects.

With his deal to take over Twitter, Mr. Musk’s ties to China are about to get even more fraught.

Like all foreign investors in China, he operates Tesla to the delight of Chinese authorities, who have shown a willingness to influence or punish companies that cross political red lines. Even Apple, the world’s most valuable company, has given in to Chinese demands, including censoring the App Store.

Musk’s extensive investments in China could be at risk if Twitter upsets the Communist Party state, which has banned the platform domestically but used it extensively to spread Beijing’s foreign policy around the world – often with false or misleading information.

At the same time, China now has a sympathetic investor taking control of one of the world’s most influential megaphones. For example, Mr. Musk said nothing publicly, such as when authorities in Shanghai closed Tesla’s factory as part of the citywide effort to contain the latest Covid-19 outbreak, even after officials in California’s Alameda County were accused of a similar move when the pandemic began in 2020.

“It’s worrisome to think about what a conflict of interest could be in these situations, looking at misinformation that could be coming out of China,” said Jessica Maddox, an assistant professor of digital media technology at the University of Alabama. “As the owner of this company now, how would he deal with that, given that all of his investments are stuck there, or most of them?”

Even Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and one of Mr Musk’s biggest rivals in tech, space and now media, weighed in — on Twitter — to question China’s potential dominion over the platform. “Has the Chinese government just gained a little influence over the town square?” Mr Bezos wrote.

Mr. Musk has not detailed his plans for changing Twitter, other than promising to make it a free speech platform while banning bots and artificial accounts that populate its user base. Even that simple promise of bots could annoy the Chinese propagandists, who have openly bought fake accounts and used them to undermine claims of human rights abuses in Xinjiang. It’s not clear whether he plans to reinstate accounts or remove labels that identify some of Beijing’s most prominent users as state officials.

Mr. Musk did not respond to an email asking for comment. A Twitter spokeswoman declined to comment.

Out of Opinion: Elon Musk’s Twitter

Commentary by Times Opinion writers and columnists on the billionaire’s $44 billion deal to buy Twitter.

What is clear is that China recognizes Twitter’s ability to disseminate information. The government banned Twitter in 2009 amid ethnic riots between Muslims and Han Chinese in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, the western region where the government later launched a mass detention and re-education campaign that the United States declared genocide.

Despite the ban, China has stepped up its own efforts to use the platform to expand the country’s power overseas. Those moves intensified in 2019 as images of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong spread across the global internet. The Chinese state media pushed back with tactics often reserved for the domestic public, accusing the Central Intelligence Agency of orchestrating the protests and repeatedly broadcasting gruesome videos of protesters’ violence, while ignoring police brutality against the crowd.

A growing chorus of Chinese diplomats, many fresh on Twitter, began to echo the harsh tone of the state media, tearing down critics and emphatically attacking countries that encouraged them. Described as “Wolf Warriors” after a popular nationalist movie, these officials gained support from a murky mass of bony accounts. By the end of 2019, Twitter had identified and deleted many of the accounts. Facebook and YouTube followed with their own purges.

Undeterred, the Chinese government redoubled its efforts as the coronavirus pandemic began. Many of the diplomats and state media representatives used Twitter to spread conspiracy theories, arguing that the coronavirus had been released from a US bioweapons lab and questioning the safety of mRNA vaccines.

Since then, inauthentic networks of bots posting alongside diplomats and state media have circulated videos challenging Xinjiang’s human rights abuses; downplaying the disappearance of Peng Shuai, the Chinese professional tennis player who accused a top Chinese official of sexual assault; and improve the success of this year’s Beijing Winter Olympics.

Through it all, Twitter has released reports on the networks, often with the help of cybersecurity experts who have linked them to the Chinese government or the Chinese Communist Party. The company was one of the first to label government-backed accounts, and more recently links to government media, as “affiliated with the Chinese state.”

Even with knowledge of China’s techniques, Twitter has found it difficult to stop the country’s information campaigns, said Darren Linvill, a professor at Clemson University who studies disinformation on social media.

“It doesn’t matter if an individual account or even thousands of accounts are suspended,” he said in a written response. “They’re creating more at an amazing speed, and by the time the account is suspended (which is often very fast), the account has already done its job.”

How Elon Musk Bought Twitter

A blockbuster deal. Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, put an end to what seemed an unlikely attempt by the famed mercurial billionaire to buy Twitter for about $44 billion. Here’s how the deal unfolded:

“A lot of misinformation, like what Russia has done, is about creating or amplifying stories. A lot of Chinese disinformation is about suppressing it,” he added.

As the new owner of Twitter, Mr. Musk may also face Chinese pressure on other issues. They include not only requests from authorities to censor information online, even outside of China’s Great Firewall — descriptions of Taiwan as anything but a province of China, for example — but also the arrests of Twitter users in China.

In China, the Musk acquisition has raised fears that officials will have even more resources to censor their critics, some of whom are using technology to circumvent the Twitter ban.

Murong Xuecun, a well-known author, was questioned by police for four hours in 2019 over two tweets he had posted three years earlier. One showed a clearly Photoshopped image of a naked Xi Jinping, China’s top leader, on a wrecking ball. The other was a cartoon where Mr. Xi shot Santa’s reindeer from the air.

“I think the Chinese government will be happy to have bought Twitter,” said Mr. Murong, “and in the coming days, the government will use its business in China to pressure it to control Twitter and help censor those who criticize the Communist Party and the Chinese government.”

Privately, he said, he and his friends call the harassment of Twitter users in China the “complete Twitter cleanup.” Murong estimates that the police had questioned tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people about their position in recent years. The punitive campaign and the growing number of Chinese officials on Twitter show that the government cares deeply about what is said on foreign social media, he said, describing the officials’ efforts as an attempt to “expell public opinion and ideological wars.” conduct” abroad.

“This government has done many similar things and will not stop in the future,” he said. “I don’t know how Musk will handle this pressure, but looking at his attitude toward China, I think he could well become a major Chinese censorship machine.”

A spokesman for China’s foreign ministry, Wang Wenbin, brushed aside questions about Twitter and Mr Musk’s investments in the country on Tuesday. “I can tell you that you are very good at speculating, but without any basis,” he replied to a question.

Even Mr. Bezos modified his post about China’s potential influence on Twitter to suggest that Mr. Musk might handily strike a balance. “Musk is extremely good at navigating this kind of complexity,” he wrote.

Still, a likely consequence of Mr. Musk’s acquisition will be less transparency. As a publicly traded company, Twitter was forced to take shareholder pressure as concerns about disinformation, account bans and regulatory enforcement affected its share price. That, in turn, forced the platform to explain its policies for countering information campaigns, such as those from China. Now that Mr. Musk plans to take the company private, there is less privilege to respond to such questions.

“Even if I just take him for what he says — his idea of Twitter as an ambitious tool to drive more democratic, pro-democracy reform here and abroad — he’s actually created a back door for China to get in and out. the very thing he has heralded as a strong defense of free speech,” said Angelo Carusone, president of the watchdog group Media Matters for America.

Steven Lee Myers reported from San Francisco, and Paul Mozur from Seoul. Claire Fu research contributed.