If you make $100,000 or more and you don't save more than your company's contribution amount, you'll fall behind and may never catch up.

If you retire later, you will have much less than you need to replace your income and maintain your standard of living.

Most read from MarketWatch

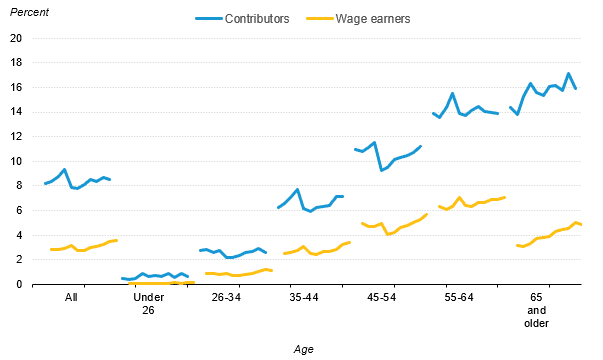

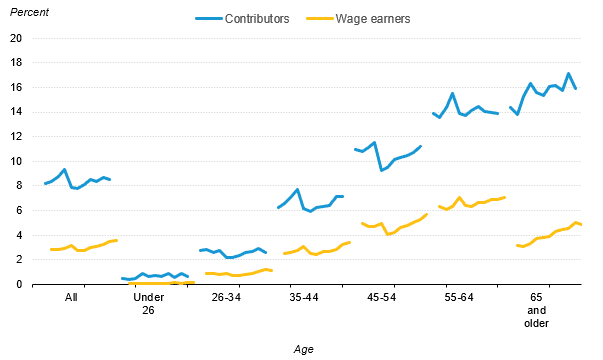

However, most high-income earners don’t pay attention to this until you’re making more than $500,000. According to data from retirement plans, there’s a large portion of people making $100,000 or more who aren’t contributing as much as they could. Vanguard’s latest report, “How America Saves,” found that only 14% maxed out their contributions in 2023, when the maximum was $22,500 (the maximum increased to $23,000 in 2024). Of those, 53% earned more than $150,000 a year.

People over 50 can contribute an additional $7,000 in catch-up contributions, but even fewer are doing so. T. Rowe Price said in a spring report that catch-up contributions for those over 50 — an additional $7,000 allowed — fell in 2023 for the first time in 10 years, from 16% to 14.7%. “It’s something we’ll have to keep an eye on, but I wouldn’t look at any one data point as the start of the trend,” said Rachel Weker, chief marketing and client experience officer for retirement plan services at T. Rowe Price.

What this dip in catch-up contributions, Karen Smith, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, told me, is that inflation and other spending may have temporarily caught up with people and they’ve reduced their contributions. People may also not have caught up with the increases in the inflation caps. These people may think they’re contributing the maximum amount, but if they haven’t adjusted their contribution levels, they may be falling short. It’s an easy fix once you realize it.

Smith has worked on studies of the behavior of 401(k) participants who make maximum contributions, and has found that income is the single most important determinant of maximum savings. After all, saving $30,000 out of a $100,000 salary would be 30 percent, and that's a huge amount to ask people to defer. “The pattern is clear: The higher the income, the more you save,” she said. But not even all high earners save at the maximum rate, and that's where the math comes in.

Percentages vs. Real Dollars

Most data and reports on contribution rates are in percentages. Vanguard found that the average contribution rate was 7.4%, helped greatly by automatic enrollment over the years. The average company match is 6%. The higher you go on the income ladder, the higher the contribution rate, but the average contribution rate for all employees is 9.2%, and that’s for those making between $100,000 and $149,999. Vanguard found that those making more than $150,000 contribute less on average.

But then there’s a discrepancy in retirement language, and we tend to talk about retirement account balances and retirement spending in dollar amounts. For example, Vanguard said its general advice was to save 12% to 15% of your annual salary, including any employer contributions, for retirement. But that’s with the added caveat that specific advice should be unique to each individual’s situation. Also, people are often told to save enough to replace 70% to 80% of their income — another percentage goal, rather than a dollar goal.

Personalized communications that do the math for people can be very effective. T. Rowe Price's Weker said, “You've got to see the dollars in the paycheck that matter to people, you've got to make it real and break it down into manageable dollar amounts.”

If you do some of that math, even simplified, you see that if you earn $100,000 and save 6% — that's only $6,000 — you won't be able to replace enough of your income in retirement. If you assume a 7% growth rate and a 22% tax rate, you'd save $6,000 a year and have $83,000 after 10 years. Increase that to the current maximum contribution of $23,000 and you'd have saved $318,000 over the same period. In retirement, that's the difference between having pennies a month to spend or thousands. You can get help personalizing these numbers from a financial advisor or your plan administrator, or use an online calculator (I used ADP's “How Much Can You Afford to Contribute” calculator.)

The math can be a shock to people who have been stuck with a 6% or so contribution rate for years, and keep hearing the message that you have to save up to the company’s contribution. Smith said people who change jobs and start over with a lower automatic contribution rate should be extra vigilant. If you’re starting over with 3%, be proactive and increase it immediately.

What needs to be drummed into high earners — especially those making well over $100,000 — is that they should save “at least” up to the company contribution, but they should keep increasing their contribution until they reach the maximum amount. If they’re lucky enough to still have a surplus of income, they should look for additional ways to save for retirement in a tax-efficient way.

For those people, “I totally agree that 6% is not going to be enough,” Weker said. “But you also have to recognize that it’s not realistic to jump from 6% to 15%, or even 20%, to make up for lost time.”

It’s a big dollar jump to go from 6% to the max at that salary level, about a $500 difference in every paycheck. But you can slow it down and get closer to the max. The first thing to do is make sure you’re not contributing less than you thought you would because the limits went up after being adjusted for inflation. Then, manually increase your contribution level with each raise or set it to automatically escalate each year.

“The biggest reason we hear that they're not saving more is because they're saving as much as they can,” Weker said. “But you can start to close that gap. Increasing your contribution by 1% a year is better than nothing, but if you can do it, go for a bigger increase, like 2%.”

Since this is pre-tax money, you may not even notice the difference.

Do you have a question about investing, how it fits into your overall financial plan, and what strategies can help you get the most out of your money? You can write to me at Please include “Fix My Portfolio” in the subject line. You can also join the conversation about pensions in our .