That mission, and the 2020 Chang'e-5 robot mission for it, are the first to return to earth since the 1970s. Together they build on what scientists have learned from missions from Apollo era, they help to unravel mysteries about what the moon was formed and why it looks like it does today, and giving instructions about the history of our solar system.

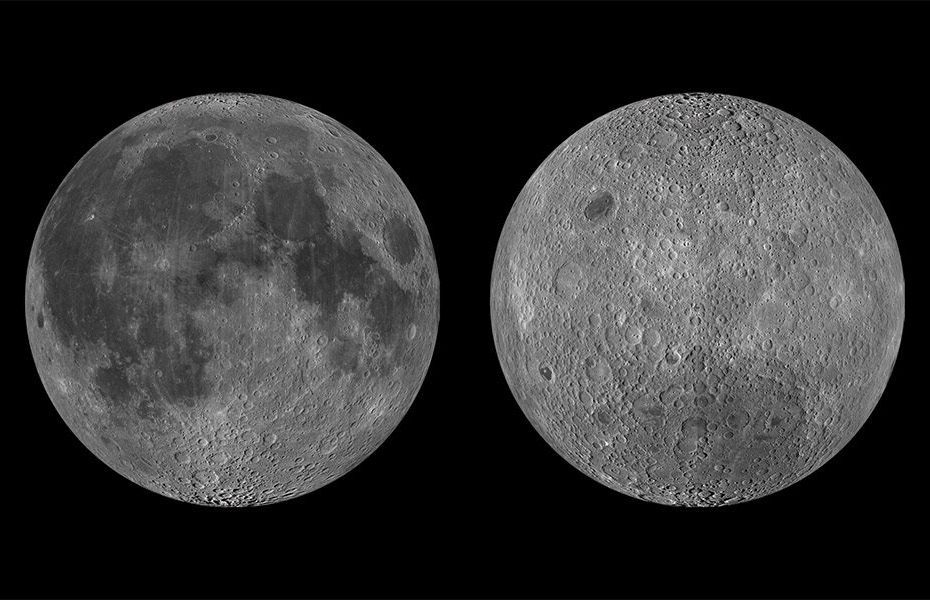

But there are large puzzles, such as why the other side of the moon – half that is always confronted from the earth – is so radically different from the nearby side. And what is behind the surprising finding that moon volcanoes were perhaps much more active than previously thought? “The more we look at the moon, the more we have discovered – and the more we realize the little we know,” says Clive R. Neal, a geologist at the University of Notre Dame who specializes in Lunar Exploration.

China's 2024 Chang'e-6 Robotland Mission brought more than four pounds from the other side of the moon back to Earth.

Credit: CNSA / Cas

Planning with NASA to send astronauts back to the surface of the Moon in 2027 for the first time since 1972, geologists are enthusiastic about which rocks they can find there and the scientific secrets that those monsters could reveal – together with which resources can become mined for a future moon base, or for renewable energy at home on earth.

Story of origin

The monsters brought home from the Moon in the 1970s through the Apollo Missions and the Luna Missions of the Soviet Union have cleared a lot about the history of the Moon. Because the lunar samples shared strong similarities with earth rocks, this weight added to the idea that the moon was formed when an object the size of Mars, Theia, collided with the Proto-Earth about 4.5 billion years ago.

Debruin from the impact was thrown into the earth and finally came to the moon. In the early days the moon was completely melted. While the Magma -Ocean cooled for hundreds of millions of years, the moon formed a crust and a cloak below. Gigantic polish of lava -filled impact craters and settled in the moon lowlands, or Maria (Latin for “seas”), while Highlands and Vulkanical domes appeared above them. Eventually the volcanism died out.

Without plate tectonics or weather were the only things that remain to change the cold, dead surface of the moon meteorites. Many of the monsters of the Apollo era were found to have formed from the heat and pressure of the effects about 3.9 billion years ago, suggesting that they were the result of a short period of intense pumming due to space strots called the late heavy bombing.

But research since the 1970s has refined or changed this photo. For example, orbital images with a higher resolution have unveiled many large impact craters that, for example, seem much older than 3.9 billion years. And meteorites found on earth, which are thought to have been cast out of different areas of the moon during major effects, it has been established that they include a huge range of ages.

All this work suggests that the asteroid bombing did not happen in one dramatic peak, but rather for a longer period of perhaps 4.2 billion to 3.4 billion years ago. In this scenario, the Apollo samples from 3.9 billion years probably all came from just one enormous impact that Rock spewed over a very wide area that happened to include the landing places of the Apollo era.

The Moon: Death or Living

Larger mysteries surround volcanism on the moon. “The canonical I learned at school was that the moon had been geological death for billions of years,” says Samuel Lawrence, a planetary scientist at the Johnson Space Center in NASA in Houston.

The long-term theory was that a small body like the moon should have losing its heat relatively quickly and an ice-cold, thought moon should not have widespread volcanic activity. Samples from Apollo era suggested that the majority of this volcanism stopped 3 billion years ago or earlier, to support the theory. But research in the past two decades has destroyed that position.

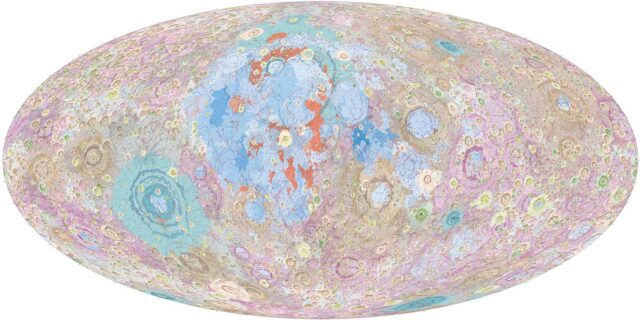

This geological map of the moon released by China in 2022 is the most detailed global card published so far and contains information that comes from the Mission 2020 Chang'e-5.

Credit: J. Ji et al / the 1: 2,500,000 scale geological map of the Global Moon 2022.

In 2014, Lawrence and colleagues stated that some pieces of irregular terrain in the middle of the dark plains, or mare, spotted by NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was the result of the volcanism that continued to less than 100 million years ago. “That is completely, completely surprising,” says Cosmochemist Qing-Zhu Yin of the University of California, Davis.

The newest sample-return missions added more concrete evidence for recent volcanism. In 2020, the Chang'e-5 robot mission landed in Oceanus Procellarum (the Ocean of Stormen)-a place that was partially picked because it looked geological young, considering how few craters had collected there. And yes, the volcanic rocks that were brought by that mission turned out to be 2 billion years old, the youngest ever taken out of the moon. “That was big news,” says planetary geoscientist Jim Head of Brown University, who worked on the Apollo missions of NASA.

Moreover, when researchers crossed through thousands of glass beads in the Chang'e-5-bodel samples, most of which are thought of by effects, they identified three that were volcanic and only 120 million years old. This finding was published last year and still needs to be verified, but if such recent dates last, they suggest that the moon may still be able to produce deep magma, even today, says Yin.

All this indicates that the moon may not have cooled as quickly as everyone thought it did. It is also possible that some of the younger volcanism could have been driven underground by radioactive elements that can generate sufficient heat to form magma and it is known to prevent them in certain places of the moon. This can, for example, explain the 120 million -year -old volcanic glass beads. But not all early volcanism can be explained in this way: the volcanic rocks of Chang'e-5, along with a 2.8-million-year-old volcanic rock that were reduced from the other side by Chang'e-6, came bronze not Enriched with these elements.

“It gives more questions than it answers,” says Neal. “It is job security for people like me – we now have new questions to answer.”

Lunar Exploration Vooruit

Donling these mysteries is a challenge with so much of the moon unexplored: although about 850 pounds of moon rock and soil have now been brought back to earth, it has all been of just a handful of locations.

Chang'e-6 expanded this photo by bringing back the first samples from the far side of the moon, taken from the South Pool Aitkenbekken, the largest, deepest and oldest impact crater of the satellite. Researchers would like to use these samples to start determining why the other side differs so dramatically from the nearby side. The questions that remain unanswered are the reason why the other side has a thicker crust and almost no mare of old lava -oceans contains compared to the nearby side.

NASA's Artemis III mission, planned for 2027 (although that could change), is intended to break more new land by landing astronauts near the South Pole of the Moon – in a place that is more representative of the typical geology of The Moon then the Apollo locations – and to bring them home a Bonanza of 150 to 180 pounds samples.

This site must offer fresh geological insights, together with more information about moon water. In 2018, scientists who analyzed orbital mapping data confirmed that there is water ice on the Poles – but in what form nobody knows yet. 'Is it frost on the surface? Are they discreet spots under the surface? Is it absorbed on mineral granules? Is it baked as a cement in the Regoliet? 'Says Nasa's Juliane Gross, who helps to develop the plans for the collection and curation of Lunar Sample for the Artemis Science team. “We don't know.”

What the Artemis astronauts think could inform current projects by China and the United States to establish permanent bases on the Moon, which can benefit from the water of the South Pole. “That's things you can breathe, that's things you can drink, it's rocket fuel,” says Lawrence.

Lunar quarry

In addition to water ice, other potential minable sources on the moon have received attention, in particular Helium-3. This stable isotope of helium is much more abundant on the moon than on earth and can be an ideal fuel for nuclear fusion (as physicists can make that process work). Commercial companies that want to fall the Moon have surfaced, including Interlune in Seattle, which is planning to bring Helium-3 back to Earth in the 2030s, followed by other sources such as rare earth elements needed for technologies such as batteries. But when Moonmijnbouw will be a reality – logistics, the economy and the legal concerns – is an open question, says Lawrence.

While some people find the idea of winning the pristine moon unpatiatingly, there may be additional hours for mining on earth, says Neal. With polar temperatures around -230 ° C (-380 ° F), the moon should be done without liquids. Developing the technologies needed for liquid-free mining can reduce concerns about the environment over waste water and tail fluids from mining on earth. “Just think of how you would bring about a revolution in mining on this planet,” he says.

But first, researchers simply have to learn more about the moon, history, geology and the possibility of extracting resources and that requires exploration up close, which will certainly result in more surprises. “Once you are on the ground, you have something like that, oh … what is this?” Gross says. She hopes that the astronauts can bring a great appetite home. “The more they return, the more we can do.”

This article originally appeared in Knipable Magazine, a non -profit publication that focuses on making scientific knowledge that is accessible to everyone. Sign up for the newsletter of the Knips magazine.