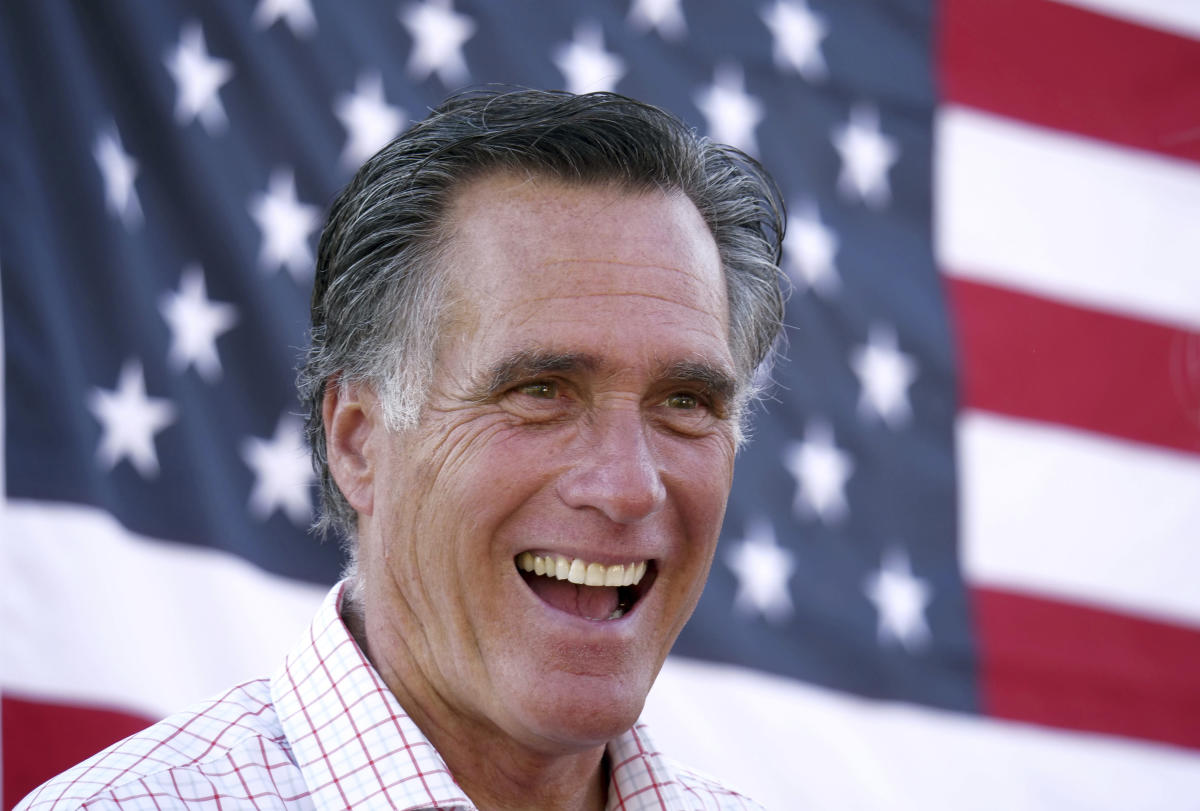

SALT LAKE CITY (AP) — Mitt Romney is not up for re-election this year. But Trump-aligned Republicans hostile to the Utah senator have made his name a recurring theme in this year’s primaries, using him as a defender and derisively labeling their rivals as “Mitt Romney.” Republicans’.

Republicans have used the concept to portray their main opponents as enemies of the Trump-era GOP in southeastern Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania. The anti-tax group Club For Growth, one of the most active super PACs in this year’s primaries, used “Mitt Romney Republican” as the central premise of an offensive ad in the North Carolina Senate primaries.

But nowhere are references to Romney Republicanism more common than in Utah. Despite its popularity with many residents here, candidates repeatedly deploy “Mitt Romney Republican” as a campaign spur attack in the run-up to Tuesday’s Republican primary.

“There are two different wings in the Republican Party,” Chris Herrod, a former state legislator who serves in Utah’s suburban 3rd congressional district, said in a debate last month.

“If you’re more on par with Mitt Romney and Spencer Cox,” he added, referring to the Utah governor, “then I’m probably not your man.”

The fact that his brand has become a powerful fodder of attack reflects the uniqueness of Romney’s position in American politics: he is the only senator with the national name recognition resulting from his candidacy for president and the only Republican to vote to become the former president. Donald Trump twice.

“It’s a bit of a mystery, really,” said Becky Edwards, an anti-Trump Republican running in the Utah Senate primaries.

As one of the most famous members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Romney is revered by many in Utah, where the Church is a dominant presence in politics and culture. He received credit for turning around the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City after a bribery scandal. After moving to Utah full-time more than a decade ago, he won the 2018 state Senate race. He did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Herrod, who went to Las Vegas to campaign for Romney in 2012, said in an interview that referring to Romney was an effective shorthand — a way of telling voters about his own belief system and that of the incumbent Republican Rep. John Curtis. Herrod has attacked Curtis for his stance on energy policy and for founding Congress’ Conservative Climate Caucus.

“It’s pretty hard to draw a line in the middle of a campaign. I just said it in terms I thought people would understand,” Herrod said.

The Curtis campaign said the congressman was more focused on legislation and billing than branding. “Congressman Curtis does not spend his time labeling himself or other Republicans,” his campaign manager, Adrielle Herring, said in a statement.

Like Herrod, Andrew Badger, a candidate running in Northern Utah’s 1st congressional district, describes his primary campaign as a “tug of war” between two competing factions within the Republican Party. He describes one as the moderate, compromise-friendly wing embodied by Romney and the other as the conservative wing embodied by Utah Senator Mike Lee, a frequent guest of FOX News who is often the Senate’s only “no” vote.

Both Badger and Herrod acknowledge that attacking Romney could turn some voters off, four years after he easily defeated a right-wing state legislator in the Republican primaries in Utah and a Democrat in the general election. But they question the durability of his support, given how the last six years have broadly changed Republican politics.

“There’s a lot more frustration, and it’s just building. I don’t think he would win a vote today, especially in a Republican primary,” Badger said.

Badger’s campaign has focused on simmering outrage over the 2020 election and anger over coronavirus mandates and how race, gender and sexuality are taught in K-12 schools. He has tried to draw a direct line between Romney and his opponent, the incumbent Rep. Blake Moore, by attacking Moore for being one of 35 House Republicans who voted to create an independent committee to investigate the January 6 insurgency.

In a district where support for Trump remains strong, he compares Moore’s vote to Romney’s two votes for impeachment.

“These people like Mitt Romney and Blake Moore, they always bend to the left when the pressure is put on them,” Badger said. “We’re not going to compromise for the sake of compromise.”

Moore did not vote for impeachment. After the Senate scuttled the commission, Moore, all but two of the House Republicans, voted against the creation of the Jan. 6 select committee that eventually met.

In response to Moore’s being labeled a “Mitt Romney Republican,” Caroline Tucker, the congressman’s campaign spokesman, said he can best be described as a “big tent Republican” who doesn’t think the legislative process is the way to go. abandonment of its conservative principles.

Jason Perry, director of the University of Utah’s Hinckley Institute of Politics, said the “Mitt Romney Republican” label might appeal to some Republican primary voters, but given Romney’s popularity, it probably won’t work in Utah, he said. .

“They’re attractive to a section of the Republican Party, but probably don’t have the numbers on that far-right side to be successful,” Perry said.