Among adults vaccinated against COVID-19, the odds of developing long-term COVID amid the omicron wave were about 20 to 50 percent lower than during the delta period, with variability based on age and time since vaccination.

The finding comes from a case-control observational study published this week in The Lancet by researchers at Kings College London. The study found that approximately 4.5 percent of ommicron breakthrough cases resulted in long-term COVID, while 10.8 percent of delta breakthrough cases resulted in the long-term condition.

While the news may seem a little reassuring to those caring for a breakthrough omicron infection, it’s cold consolation to public health in general, as the omicron coronavirus variant is much more transmissible than delta.

“Many more people were infected with omicron first than with delta,” Kevin McConway, professor emeritus of applied statistics at the Open University, said in a statement. “So even if the percentage of people infected who got long-term COVID during the two waves is on the scale that these researchers report — which may well be — the actual number of people who reported long-term COVID after being first infected during ommicron still much larger than during delta.”

For The Lancet study, researchers examined self-reported symptom data from 56,003 British adults who were first infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the ommicron wave and 41,361 British adults who were initially infected during the delta period.

The researchers, led by Claire Steves, a senior clinical lecturer at King’s College London, defined long-term COVID as having new or persistent symptoms four weeks or more after the onset of acute COVID-19, as it is defined in the US National Institute for Guidelines for Excellence in Health and Care.

Significant burden

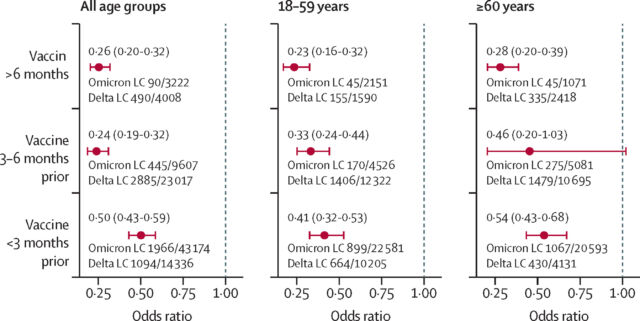

When the researchers adjusted for age, time since vaccination, and other health-related factors, the relative odds of developing COVID long after ommicron ranged from about 23 percent to 50 percent. The odds were greatest when people were closer to vaccination (within less than three months) and were 60 years of age and older.

The study has limitations, the most obvious of which is that it is based on self-reported symptom data and does not address the severity of the long-term COVID cases. There was also insufficient data to look at long COVID rates among unvaccinated people, and the study did not include data on rates in children.

The study was also done during the BA.1 wave, as David Strain, a clinical associate professor at the University of Exeter Medical School, noted in a statement. The subsequent ommicron subvariants, including BA.2, BA.2.12.1, and the emerging BA.4 and BA.5, may have different profiles with regard to long-term COVID risk.

But even if the 4.5 percent estimate holds up over time, that translates into many people developing COVID long-term. This “creates a significant public health burden of this disease with no known treatment or even reliable diagnostic test,” Strain added.

Reiterating the sentiment, Steves said in a statement: “The omicron variant appears to be significantly less likely to cause long-term COVID than previous variants, yet 1 in 23 people who contract COVID-19 continue to have symptoms for more than four weeks. Given the number of people affected, it is important that we continue to support them at work, at home and within the [National Health Service]†