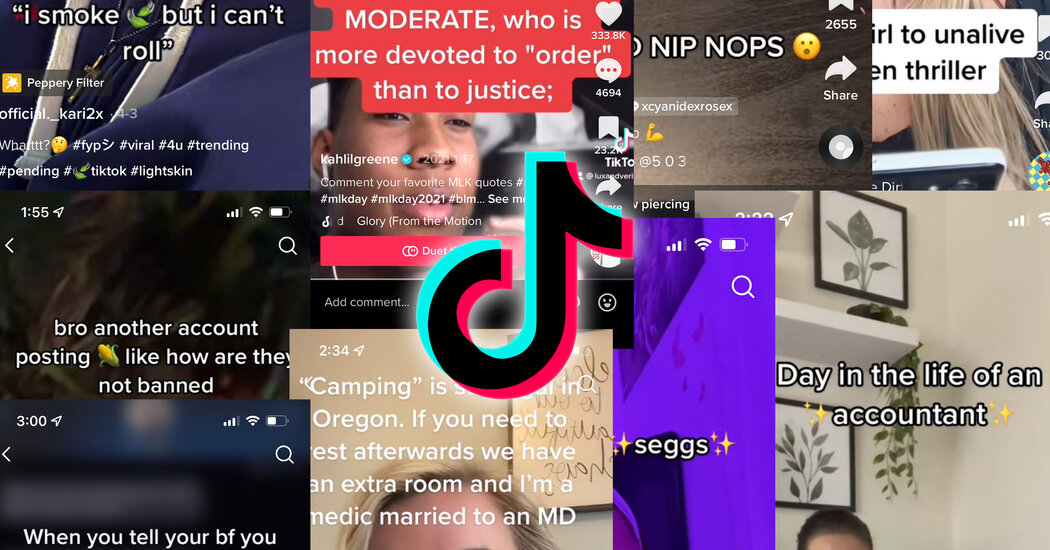

To hear some people on TikTok tell it, we’ve spent years in a “panoramic.” Or maybe it was a ‘panini press’. Some are in the “leg booty” community and firmly against “cornucopia”.

If it all sounds like a foreign language to you, that’s because it is.

TikTok creators have gotten into the habit of coming up with substitutes for words they fear could affect how their videos are promoted on the site, or violate moderation rules.

So in 2021, someone describing a pandemic hobby would have thought (perhaps incorrectly) that TikTok would falsely flag it as part of a crackdown on pandemic misinformation. So the user could have said “panoramic” or some similar-sounding word instead. Similarly, fears that sexual topics would cause problems led some creators to use “leg booty” for LGBTQ and “cornucopia” instead of “homophobia”. Sex became seggs.

Critics say the necessity of these evasive neologisms is a sign that TikTok is too aggressive in its moderation. But the platform says it needs a firm hand in a free-roaming online community where many users try to post harmful videos.

Those who do not follow the rules may be banned from posting. The video in question can be deleted. Or it could simply be hidden from the For You page, which suggests videos to users, the main way TikToks are widely distributed. Searches and hashtags that violate the policy may also be redirected, the app said.

When people on TikTok think their videos have been hidden because they touched on topics the platform doesn’t like, they call it “shadow banning,” a term also used on Twitter and other social platforms. It’s not an official term used by social platforms, and TikTok hasn’t confirmed it even exists.

The new vocabulary is also called algospeak.

It’s not unique to TikTok, but it’s one way creators envision they can get around moderation rules by misspelling words, replacing them, or finding new ways to point out words that could otherwise be red flags that could lead to delays in posting would lead. The words can be made up, such as “alive” for “dead” or “dead.” Or they may include new spellings – le $bian with a dollar sign, for example, which TikTok’s text-to-speech pronounces as “le dollar bean.”

In some cases, the users are just having fun instead of worrying about their videos being deleted.

A TikTok spokeswoman suggested users may be overreacting. She pointed out that there were “a lot of popular videos about sex,” and sent links to a stand-up set from Comedy Central’s page and videos for parents on how to talk to kids about sex.

Here’s how the moderation system works.

The app’s two-tiered content moderation process is a large net that attempts to catch any references that are violent, hateful, sexually explicit, or spread misinformation. Videos are scanned for violations and users can flag them. Those found in violation will be automatically removed or referred for review by a human moderator. From April to June this year, about 113 million videos were removed, 48 million of them due to automation, the company said.

While much of the removed content involves violence, illegal activity, or nudity, many language violations seem to be in a gray area.

Kahlil Greene, who is known on TikTok as the Gen Z Historian, said he quoted Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had to change to a video about people laundering King’s estate. So he wrote the phrase Ku Klux Klanner as “Ku K1ux K1ann3r” and spelled “white moderate” as “wh1t3 moderate”.

Partly due to frustrations with TikTok, Mr. Greene started posting his videos on Instagram.

“I can’t even quote Martin Luther King Jr. without taking so many precautions,” he said, adding that it was “quite common” for TikTok to flag or remove an educational video about racism or black history, thus reducing research, script time and other work he has done.

And the possibility of an outright ban is “a huge concern,” he said. “I’m a full-time content creator, so I monetize the platform.”

Mr. Greene says he makes money from brand deals, donations and speaking engagements that come from his social media following.

Alessandro Bogliari, the CEO of the Influencer Marketing Factory, said the moderation systems are smart, but can make mistakes. That’s why many of the influencers his company hires for marketing campaigns use algospeak.

Months ago, the company, which helps brands connect with younger users on social media, used a popular song in Spanish in a video with a profanity. forbidden. “It’s always hard to prove,” he said, adding that he couldn’t rule out that the total audience wasn’t there or that the video simply wasn’t interesting enough.

TikTok’s guidelines don’t list banned words, but some things are consistent enough that creators know to avoid them, and many share lists of words that triggered the system. So they refer to nipples as “nip nops” and sex workers as “accountants”. Sexual Assault Is Just “SA” And when Roe v. Wade was overturned, many began to refer to getting an abortion as “camping.” TikTok said the topic of abortion was not banned on the app, but that the app would remove medical misinformation and community guidelines violations.

Some creators say TikTok is unnecessarily harsh with content about gender, sexuality and race.

In April, the TikTok account of the advocacy group Human Rights Campaign posted a video saying it had been temporarily banned from posting after using the word “gay” in a comment. The ban was quickly reversed and the comment reposted. TikTok called this an error by a moderator who did not review the comment carefully after another user reported it.

“We are proud that members of the LGBTQ+ community choose to create and share on TikTok, and our policies are aimed at protecting and amplifying these voices on our platform,” a TikTok representative said at the time.

Nevertheless, Griffin Maxwell Brooks, a creator and student at Princeton University, has noticed videos being flagged with profanity or “markings of the LGBTQ+ community.”

When Mx. Brooks writes subtitles for videos, they said they usually replace profanity with “words that are phonetically similar.” Fruit emojis stand for words like “gay” or “queer.”

“It’s really frustrating because the censorship seems to vary,” they said, and seems to disproportionately affect queer communities and people of color.

Will these words stick?

Probably not most of them, experts say.

Once older people start using online slang popularized by young people on TikTok, the terms become “obsolete,” said Nicole Holliday, an assistant professor of linguistics at Pomona College. “Once the parents have it, you have to move on to something else.”

The extent to which social media can change language is often exaggerated, she said. Most English speakers don’t use TikTok, and those who do may not pay much attention to the neologisms.

And like everyone else, young people are adept at “code-switching,” meaning they use different languages depending on who they’re with and the situations they’re in, Professor Holliday added. “I teach 20-year-olds — they don’t come to class and say ‘legs and booty.'”

But on the other hand, she said, few could have predicted how long the slang word “cool” would persist as a designation for anything generally good or fashionable. Researchers say it emerged on the jazz scene of the 1930s nearly a century ago, receding from time to time over the decades, but coming back again and again.

Now, she said, “everyone who speaks English has that word.” And that’s pretty cool.