KW Lee, a groundbreaking Asian American journalist whose report led to the release of a Korean immigrant in the death cell in California, and who treated the Koreatown community, died in the Riots of Los Angeles of 1992, died in his house in Sacramento on 8 March. He was 96.

His death was confirmed by his daughters, Sonia Cook and Diana Regan.

Mr. Lee was an immigrant who found his way to West Virginia in the 1950s and began to treat an extremely broad journalistic career through election fraud and poverty in Appalachia.

His articles for the Sacramento Union in the 1970s about the manslaughter of prisoner Chol Soo Lee were photographed and passed on by social workers, students and grandmothers in various Asian communities Koreans, Chinese, Japanese-Severen in a movement to free him. It was an early example of political activism based on a shared Asian American identity.

Mr. Lee was the editor of the English -language edition of Korea Times in Los Angeles when violence broke out in April 1992, after the acquittal of four white police officers at the beating of Rodney King, a black man. More than 2,000 companies in Korea, many in or adjacent to poor black neighborhoods, were damaged, which represents half of the destruction of the city -wide riots.

Mr. Lee described the complex roots of tensions between Korean and Afro -American inhabitants. “For Korean newcomers,” he wrote in a tormented editorial, “it is a sobering memory that they have replaced their Jewish counterparts as a scapegoat for all ailments, imaginated or real, of the impoverished black districts destroyed by crime.”

He also accused the regular media of the sensational sensational tensions, of which he said he fed stereotypes of rude and greedy immigrant shop owners and fed the violence against them.

“Shoplifting and racial threats and intimidations are part of the daily life of almost every Korean American merchant in inner cities,” he wrote.

His coverage tried to humanize Korean immigrants and build a bridge over racial and ethnic lines.

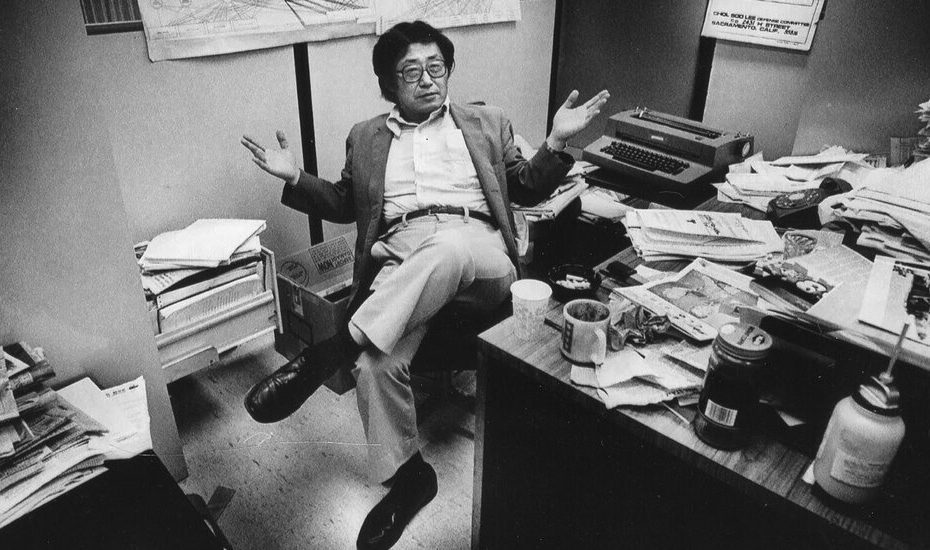

Mr Lee, who was sometimes described as the dean of Asian American journalism, took a top job in the so-called ethnic press after years as a research reporter in regular newspapers, most in particular the Sacramento Union, which he added in 1970. There he exposed corruption in the state government of California, among other things, how legislation is in charge of Lavus Pensions.

“He was shocked by corruption. It made him angry,” Ken Harvey, his editor at the Union, told the Sacramento Bee in 1994.

Mr Lee also wrote with the writing of more than 100 articles that exposed problems with the jury ordering of Chol Soo Lee, who was brought to the US from Seoul at the age of 12, in the murder of a Chinese gang leader in San Francisco. After he was found guilty in 1974 and was sentenced to life imprisonment, he killed another prisoner in a knife fight that self-defense was and landed in the death cell in the San Quentin prison.

“Long isolated and removed from the fragmented Korean community, Lee has maintained his innocence,” Mr Lee wrote in one article. “Few listened to his Gedempte Call for justice. Help, if present, did not come enough and too late.”

His report identified errors in the original conviction, which raised questions about the difficulty of identifying suspects in racial lines. Although the murder took place during daylight hours in Chinatown, were the only eyewitnesses that the police found to testify white tourists. The arresting officer identified Chol Soo Lee as 'Chinese'.

“The case resonated deeply with many Asian Americans in different ethnic groups because they had felt this racism, this discrimination, not completely haumanized in American society,” said Julie Ha, a director of the documentary “Free Chol Soo Lee” (2022), said in an interview.

Proponents protested outside of court buildings and raised money for a legal defense.

During a new process in 1982, Chol Soo Lee was acquitted of the murder of Chinatown. His conviction in prison that put death was a plea the following year and he ran free after almost a decade in prison.

Between Chol Soo Lee and himself, Mr Lee saw a “very thin line,” he said later. He has credited his many years of reporting on the matter with a waking up of his latent Korean identity.

Mr. Lee left mainstream newspapers to work in the Korean American press. In 1979 he was the founder of the short -lived Koreatown Weekly, in Los Angeles, and in 1990 he became editor of the English edition of Korea Times.

“He realized that the stories of Korean Americans were largely unknown – we were an invisible minority,” said Mrs. Ha, who was a trainee at Korea Times under Mr Lee.

Former employees of Korea Times tributed to Mr Lee in “SA I Gu: Korean and Asian American journalists who Truth to Power Writing to Power”, a book from 2023, published by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. (“Sa I Gu” is the Korean American term for the Los Angeles riots from 1992, based on the figures 4-2-9, before April 29, when the violence began.)

“Mr. Lee was genetically attracted by the oppressed,” wrote John Lee, one of the contributors of the book, in an e -mail, adding that KW Lee was known for many aphorisms, including “Follow the scent.”

Kyung Won Lee was born on June 1, 1928 in Kaesong, in what is now Noord -Korea, the youngest of seven children of Hyung Soon Lee and soon Bok Kim. His father owned a confectionery factory, but the family sold it to win his release after he was held in 1919 for his protest of the Japanese occupation of Korea.

Against the wishes of his parents, Kyung won volunteering for a Japanese Air Cadet Corps unit during the Second World War and trained as a escape radar operator, but he avoided the effort because of the surrender of Japan in 1945. He emigrated to the United States in 1950, six months before the breakdown of the Korean war and settled in Tennesse. He later registered at West Virginia University, where he graduated in 1953 with a BS in journalism.

His first newspaper job was in the Kingssport Times-News, in Tennessee, in 1956. Two years later he was hired by the Charleston Gazette, in the capital of West Virginia. The newspaper sent him to Mingo County, deep in Appalachia, to write about the political and economic influence of King Coal.

His Muckracking region local officials of the region. They called the newsroom of the newspaper and told his editors: “Don't send that Chinaman back here,” Mr Lee remembered in an interview with WVU Magazine, an alumni publication, in 2017.

In 1959 he married Peggy Flowers, a nurse in the first aid he had met during work in Charleston. She died in 2011. In addition to their daughters, Mrs. Cook and Mrs. Regan, he is survived by a son, Shane Lee; Six grandchildren; And three great -grandchildren.

Liver disease ran in the birth family of Mr. Lee. His both parents and all six brothers and sisters died, said Mrs. Cook. During the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, he edited Korea Times in English from the hospital room where he was awaiting a liver transplant.

The life -saving transplantation came through. Later that year, when he received the John Anson Ford Award from the Los Angeles County Human Relations Commission, he said in his acceptance speech that his new liver could have come from a black, white or Asian donor.

“What does it matter?” he said. “We are all entangled in an unbroken human chain of mutual dependence and mutual survival. And what really matters is that we all belong to each other during our earthly passage.”