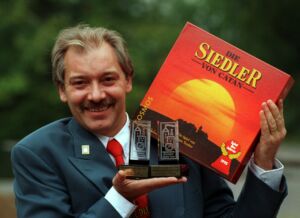

Picture Alliance via Getty Images

I was in my early thirties when I first played The Settlers of Catan. I had been in a bar with a small group on a freezing winter night in 2012 in Buffalo, New York. One of us, eager to share his recent obsession, declared it was time for the next leg of the outing. We went to his barely unpacked new apartment nearby. He took the game out of a plastic carrying case, opened it on a rickety dinette table, and set the board down, apologizing for the moisture-warped edges. I took a picture (on my HTC Thunderbolt) because after having a few I wanted to make sure I remember this game with the wooden pieces and the weird amount of sheep.

Kevin Purdy

It was an inauspicious start to the rest of my board game life. Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s and as my young adult life began in the early 2000s, I thought of board games as something you do in situations where you can’t do anything else: power outages, cabins in the woods, get-togethers with people with no known shared interests. They wouldn’t really be pleasureand you wouldn’t necessarily play but someone would be the winner and time would pass. Katan that changed – for me and for what are now legions of modern board game aficionados.

From a German cellar to 32 million copies

You may have seen the news this week that Klaus Teuber, the German designer created it The Settlers of Catan (just now Katan), died on April 1 at the age of 70. Teuber developed Die Siedler of Catan in the early 1990s, toying with ideas about Icelandic settlements, tinkering in his basement while working full-time in a dental lab. He would come up with new iterations for his wife and kids to test every weekend, he told The New Yorker. The breakthrough, he said, was using hexagonal tiles instead of squares.

Uta Rademacher via Getty Images

Teuber has made other memorable games, with two pre-Katan titles winning the best board game prize in Germany (and the world), the Spiel des Jahres. But Katan was the right game at the right time. Its release in 1995 gave it time to infiltrate European gamers, then US Eurogame enthusiasts and, crucially, the still nascent internet. BoardGameGeek.com wouldn’t appear until 2000, but by then Katan had done his groundwork. It provided a face-to-face, objects-on-a-table counterpoint to a culture that quickly adopted online chatter and screen-based gaming. A 2009 article in the Wall Street Journal captures the game as it overtook Silicon Valley (with cameos from StumbleUpon, Zynga, RapLeaf, and other terrible 2009 names).

Guido Teuber, Klaus’ son, said sales in Silicon Valley peaked in 2007 to 2008, just after the game became available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. He told the Journal he was surprised at the “techie interest” at first, but “then we saw how they need social interaction after sitting in front of a monitor all day.”

Roland Weihrauch/photo alliance via Getty Images

What makes Katan (and Eurogames) different

The easiest way to explain what makes Katan and other “Eurogames” that differ from mainstream American board games is that they are relatively easy to learn, yet offer much deeper layers of strategy for those who keep playing. They also typically don’t let players be kicked out of the game until the final score is tallied, they rely more on strategy, resource management, and risk/reward considerations than luck, and they have fewer direct conflicts between players.

Check out the list of Spiel des Jahres winners and finalists since then Katan‘S 1995 release, and you get the gist of the types of games I’m talking about: Carcassone, Puerto Rico, Ticket to Ride, Dominion, Pandemic, Forbidden Island, 7 Wonders, Terraforming Mars, Azul, Wingspan. It is possible to win these games the first time you play, but experienced players have an edge, which is softened a bit by luck. They give you something to think about when it’s not your turn, so you’re not just sitting around waiting, but many such games aren’t so demanding that they preclude pizza, beer, and side conversations. And they have a playing time printed on the box, usually 90 minutes or less, which is realistic (if everyone knows the rules).