Ed Lu wants to save the Earth from killer asteroids.

Or at least, if a large space rock is headed our way, Dr. Lu, a former NASA astronaut with a PhD in applied physics, wants to find it before it hits us — hopefully with years of warning and a chance for humanity to deflect it.

On Tuesday, the B612 Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supports Dr. Lu helped found more than 100 asteroids. (The foundation’s name is a nod to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s book, “The Little Prince”; B612 is the protagonist’s home asteroid.)

That in itself is unobtrusive. New asteroids are constantly being reported by skywatchers around the world. That includes amateurs with backyard telescopes and robotic surveyors that systematically scan the night sky.

Remarkably, B612 has not built a new telescope or even made new observations with existing telescopes. Instead, researchers funded by B612 applied cutting-edge computing power to years-old images — 412,000 of them in the digital archives of the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, or NOIRLab — to sift asteroids from the 68 billion dots of cosmic light. captured in the images.

“This is the modern way of doing astronomy”† said Dr. lu.

The research contributes to the “planetary defense” efforts of NASA and other organizations around the world.

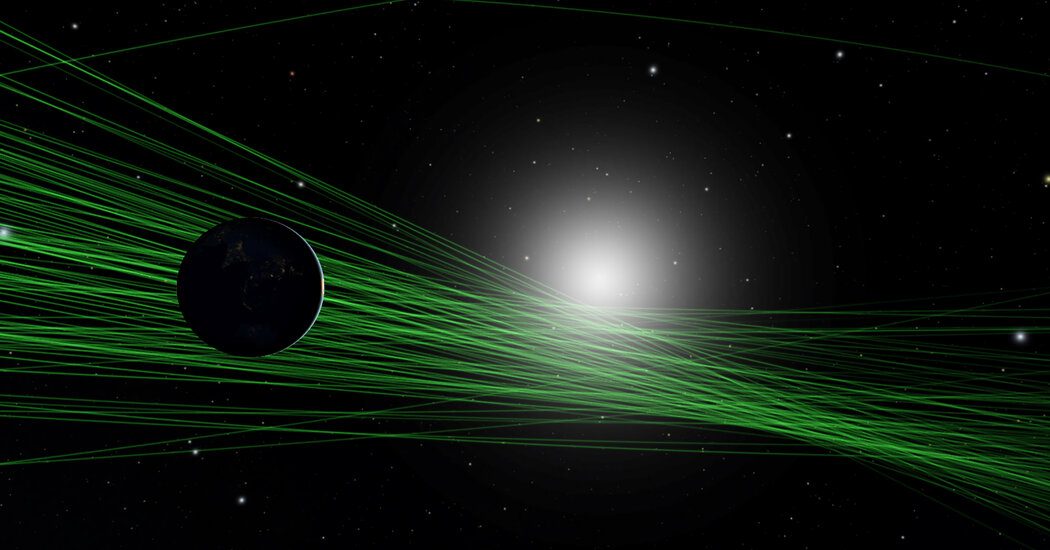

Today, of the estimated 25,000 near-Earth asteroids at least 460 feet in diameter, only about 40 percent of them have been found. The other 60 percent — about 15,000 space rocks, each with the potential to unleash the energy equivalent of hundreds of millions of tons of TNT in a collision with Earth — go unnoticed.

B612 worked with Joachim Moeyens, a graduate student at the University of Washington, and his doctoral advisor, Mario Juric, a professor of astronomy. She and colleagues at the university’s Institute for Data Intensive Research in Astrophysics and Cosmology developed an algorithm capable of examining astronomical images, not only identifying those points of light that could be asteroids, but also figuring out which ones. points of light in images taken on different nights are actually the same asteroid.

Essentially, the researchers developed a way to discover what has already been seen but not noticed.

Usually, asteroids are discovered when the same part of the sky is photographed several times over the course of one night. A swath of the night sky contains a multitude of points of light. Distant stars and galaxies remain in the same arrangement. But objects much closer, within the solar system, move quickly and their positions shift over the course of the night.

Astronomers call a series of observations of a single moving object during a single night a “tracklet.” A tracklet gives an indication of the object’s movement and points astronomers where they might look for it on another night. They can also search older images for the same object.

Many astronomical observations that are not part of systematic asteroid searches inevitably record asteroids, but only at a single time and place, not the multiple observations needed to build tracks.

For example, the NOIRLab images were taken primarily by the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope in Chile as part of a survey of nearly one-eighth of the night sky to map the distribution of galaxies in the Universe.

The extra spots of light were ignored because they weren’t what the astronomers were studying. “It’s just random data in random images of the sky,” said Dr. lu.

But for Mr. Moeyens and Dr. Juric, a single point of light that is not a star or galaxy is the starting point for their algorithm, which they called Tracklet-less Heliocentric Orbit Recovery, or THOR.

The motion of an asteroid is precisely determined by the law of gravity. THOR constructs a test track that corresponds to the observed point of light, assuming a certain distance and speed. It then calculates where the asteroid would be on the following and previous nights. If a bright spot appears in the data there, it could be the same asteroid. If the algorithm can connect five or six observations in a few weeks, that’s a promising candidate for an asteroid discovery.

In principle, there are an infinite number of possible test tracks to explore, but that would take an impractical eternity to calculate. In practice, because asteroids are clustered around certain orbits, the algorithm only needs to consider a few thousand carefully chosen possibilities.

Still, calculating thousands of test tracks for thousands of potential asteroids is a huge calculation task. But the advent of cloud computing — massive computing power and data storage scattered across the Internet — makes that possible. Google contributed time on its Google Cloud platform to the effort.

“It’s one of the coolest applications I’ve seen,” said Scott Penberthy, director of applied artificial intelligence at Google.

So far, the scientists have searched about one-eighth of data from a single month, September 2013, from NOIRLab’s archives. THOR produced 1,354 possible asteroids. Many of them were already in the catalog of asteroids maintained by the Minor Planet Center of the International Astronomical Union. Some of them had been sighted before, but only for one night and the tracklet wasn’t enough to determine orbit with confidence.

The Minor Planet Center has confirmed 104 objects as new discoveries so far. The NOIRLab archive contains seven years of data, suggesting there are tens of thousands of asteroids waiting to be found.

“I love it†said Matthew Payne, director of the Minor Planet Center, who was not involved in the development of THOR. “I find it extremely interesting and it also allows us to make good use of the archive data that already exists†

The algorithm is currently configured to only find asteroids in the main belt, those with orbits between Mars and Jupiter, and not near-Earth asteroids, the ones that could collide with our planet. Identifying asteroids near Earth is more difficult because they move faster. Different observations of the same asteroid can be further separated in time and distance, and the algorithm must do more math to make the connections.

‘It will certainly work,’ said Mr Moeyens. “There’s no reason why it couldn’t be. I just haven’t had a chance to try it yet.”

Not only does THOR have the ability to discover new asteroids in old data, but it can also transform future observations. Take, for example, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which is currently under construction in Chile.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the Rubin Observatory is an 8.4-meter telescope that will repeatedly scan the night sky to track what changes over time.

Part of the observatory’s mission is to study the large-scale structure of the universe and spot distant exploding stars, known as supernovas. Closer to home, it will also see a host of smaller-than-planet bodies whizzing around the solar system.

Several years ago, some scientists suggested that the Rubin telescope’s observation patterns could be modified so that it could identify more asteroid trails and thus locate more of the dangerous, yet undiscovered asteroids more quickly. But that change would have slowed other astronomical research.

If the THOR algorithm works well with the Rubin data, the telescope will not have to scan the same part of the sky twice a night, but instead cover twice as much area.

“That could be revolutionary in principle, or at least very important,” said Zeljko Ivezic, the telescope’s director and an author of a scientific paper that described and tested THOR through observations.

If the telescope could return to the same spot in the sky every two nights instead of every four, that would help other research, including looking for supernovae.

“That would be another impact of the algorithm that doesn’t even have to do with asteroids,” said Dr. Ivezic. “This shows beautifully how the landscape is changing. The ecosystem of science is changing because software can now do things that you didn’t even dream of 20, 30 years ago, that you wouldn’t even think of†

for dr. Lu offers THOR another way to achieve the same goals he had ten years ago.

At the time, B612 had its sights set on an ambitious and much more expensive project. The nonprofit went on to build, launch and operate its own space telescope called Sentinel.

At the time, Dr. Lu and the other leaders of B612 are frustrated by the slow pace of the search for dangerous space rocks. In 2005, Congress passed a mandate for NASA to locate and track 90 percent of nearby Earth asteroids 460 feet or more in diameter by 2020. But lawmakers never provided the money NASA needed to complete the task, and the deadline passed with less than half of those asteroids found.

Raising $450 million from private donors to insure Sentinel was difficult for B612, especially as NASA was considering its own space telescope for finding asteroids.

When the National Science Foundation gave the green light to build the Rubin Observatory, B612 reevaluated its plans. “We could turn quickly and say, ‘What’s another approach to solving the problem we need to solve?'” said Dr. lu.

The Rubin Observatory should make its first test observations in about a year and become operational in about two years. Ten years of Rubin sightings, along with other asteroid searches, could finally reach Congress’ 90 percent target, said Dr. Ivezic.

NASA is also accelerating its planetary defense efforts. The asteroid telescope, called NEO Surveyor, is in the preliminary design phase and should be launched in 2026.

And later this year, his Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission will smash a projectile into a small asteroid and measure how much that changes the asteroid’s orbit. China’s national space agency is working on a similar mission.

For B612, instead of wrangling a telescope project costing nearly half a billion dollars, it can contribute with less expensive research efforts like THOR. Last week, it announced it had received $1.3 million in gifts to fund further work on cloud-based computing tools for asteroid science. The foundation also received a grant from Tito’s Handmade Vodka that will match up to $1 million from other donors.

B612 and Dr. Lu are not just trying to save the world now. “We are the answer to a trivia question about how vodka is related to asteroids.” he said.