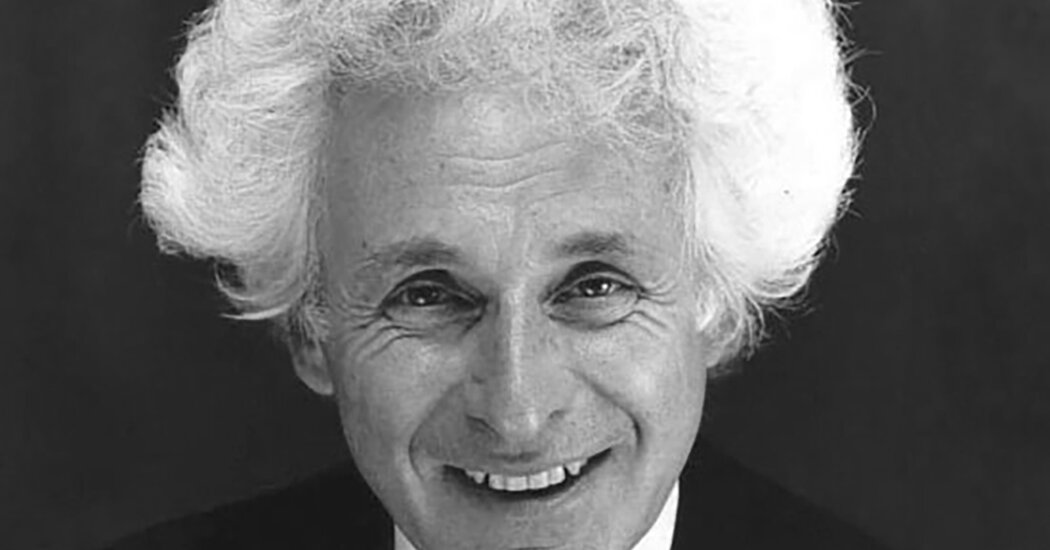

Jerry Mander, whose iconoclastic mindset led him to create ad campaigns for non-profit organizations, such as one for the Sierra Club in 1966 to fight a plan to build two dams in the Grand Canyon and an organization to raise awareness about the dangers of economic globalization, died April 11 at his home in Honokaa, Hawaii. He turned 86.

His son Kai confirmed the death, but gave no cause.

In 1966, Mr. Mander was working at Freeman & Gossage, an advertising agency in San Francisco, when David Brower, the executive director of the Sierra Club, asked for help formulating the conservation group’s opposition to the construction of hydroelectric dams by the federal government on the Colorado River.

The full-page newspaper ads created by the agency drew national attention and angered proponents of the project in Congress, who denied the Sierra Club’s claims that the dams would overflow and desecrate the canyon.

“Only you can now save the Grand Canyon from a flood…for profit,” read the headline of one of the advertisements written by Mr. Mander. It contained coupons with messages that readers could clip and send to government officials, including President Lyndon B. Johnson and Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.

Clipping and posting the coupons “radicalizes the sender at least as much as it impresses the recipient,” Mander wrote in “70 Ads to Save the World: An Illustrated Memoir of Social Change” (2022). For someone in authority receiving 5,000 coupons, he added, “the action “could actually have a much bigger impact and attract a lot more attention than, say, thousands of tweets.”

The campaign – and other factors – led the government in early 1967 to drop its plan to build the dams. (It also caused the Internal Revenue Service to revoke the Sierra Club’s tax exemption over attempts to influence the legislation.)

Working with the Sierra Club helped Mr. Mander see a future where he could use his marketing skills for the common good, rather than helping customers maximize their profits.

After Howard Gossage, the founder of the ad agency, died in 1969 and the agency later folded, Mr. Mander helped create Public Interest Communications, which helped nonprofits and individuals with campaigns such as one against development in San Francisco and another against a water project in San Francisco. Northern California.

He later moved to the Public Media Center, where he spent about 20 years as a senior fellow writing ads for non-profit organizations such as Planned Parenthood, Public Citizen, Earth Island Institute (which Mr. Brower founded), and the Sierra Club.

One of his high-profile ads for a Planned Parenthood campaign for abortion rights appeared in newspapers in 1985. It contained photographs of two women, along with their stories of having illegal abortions; a photo of a fire-bombed abortion clinic; a list of nine reasons why abortion is legal; and three receipts with different messages, one addressed to Attorney General Edwin Meese III.

“He was a countercultural type who wanted to reset the framework of how people viewed modern life,” Jono Polansky, creative director of the Public Media Center, said in a telephone interview. In the full-page print ads that were Mr. Mander’s specialty, Mr. Polansky added, “He could break down a problem and say, ‘How do you tell a story to people and give them a place to do something about it?'”

Jerold Irwin Mander was born May 1, 1936 in the Bronx and grew up in Yonkers, NY, in Westchester County. His father, Harry, owned a business in Manhattan’s clothing district that made liners for menswear. His mother, Eva Mander, was a housewife. Little did his parents know that their son’s name sounded exactly like the political term for manipulating electoral districts to favor one party, Kai Mander said.

After graduating from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1957 with a bachelor’s degree in economics, Mr. Mander earned a master’s degree in international economics from Columbia Business School in 1959. He briefly worked in public relations for the Worthington Corporation in Newark before moving to San Francisco where he got a job in the publicity department of the San Francisco International Film Festival.

He soon opened his own public relations firm, whose clients included The Committee, an improv theater group, among his clients. In early 1966, he created a bold ad in The San Francisco Chronicle mocking what he remembered as a planned Pentagon airdrop of toys to Vietnamese children. The ad promised that the committee would collect war toys (two whimsical recommendations: a plastic bazooka and a nuclear tank that ejects napalm) for the Department of Defense and drop them on the Pentagon from a helicopter.

His full-time advertising career began soon after with a call from Mr. Gossage, who said he loved the war toy ad and asked him to join his agency, where he became a partner.

His work increasingly reflected his suspicions about the social effects of technology, advertising and television. Those concerns led him to write “Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television” (1978), in which he argued, among other things, that the medium isolates viewers, dulls their minds, and lays the foundations for an autocracy.

In the 1990s, he focused on economic globalization, embodied in organizations such as the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

In the early 1990s, he founded a think tank, the International Forum on Globalization, by convening activist leaders concerned about the negative impact of the organizations’ policies on global health and environmental standards, food security, and jobs around the world .

“He understood the issues, knew all the opinion leaders and had an amazing ability to summarize very complicated issues and make them meaningful to people’s lives,” said Debbie Barker, a former co-director of the forum.

Over the next decade, the group published reports on various issues and held multi-day teach-ins attended by as many as a few thousand people in cities where the organizations met. At the 1999 World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle, police used tear gas against protesters who had blockaded parts of downtown.

“We are entering the world of corporate rule,” Mr. Mander told a crowd of 1,300 at the teach-in in Seattle. He added that of the world’s largest economies, 52 were companies, and “while corporate profits are higher than ever before, real wages are falling. CEOs of large companies earn 419 times more than the average line worker.”

The think tank was largely funded by Douglas Tompkins, the conservationist and founder of the Esprit and North Face clothing brands. He also hired Mr. Mander as program director of the Foundation for Deep Ecology, which is dedicated to wildlife conservation.

The forum’s momentum slowed after the September 11 terrorist attacks when many activists began holding anti-war protests.

“Every time I talked to him, Jerry would say, ‘We’ve got to get the IFG back together,'” said John Cavanagh, the group’s president and director of the Institute for Policy Studies. “Others would say it wasn’t a success because we didn’t stop those institutions. But it slowed them down and aroused skepticism about them.”

In addition to his son, Kai, Mr. Mander is survived by another son, Yari, and his wife, Koohan Paik-Mander. His marriages to Anica Vesel and Elizabeth Garsonnin ended in divorce.