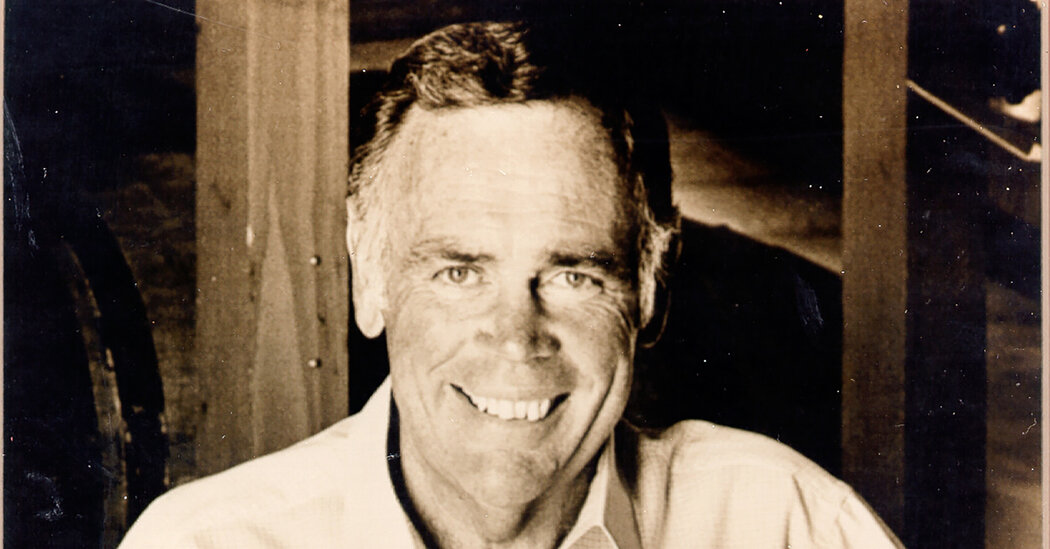

Jack Cakebread, who along with his wife, Dolores, turned a 22-acre cattle ranch in Rutherford, California into one of Napa Valley’s leading wineries while helping to propel the once obscure region to global winemaking stardom, died at Apr 26 in Napa. He was 92.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his son Dennis, the president of Cakebread Cellars.

Mr. Cakebread, an auto mechanic with a side job in photography, was returning from a photo shoot in northern Napa County when he visited some friends of the family on their farm in Rutherford in 1972. He was 42 years old and only vaguely curious about what a life outside of auto repair might look like.

“I said to them very casually, ‘You know, if you ever want to sell this place, let me know,’ and I drove home,” he said in an interview with journalist Sally Bernstein. “I came home and the phone rang.”

The next day, Mr. Cakebread and his wife bought the farm with a $2,500 down payment. The two couples wrote the contract on a yellow notepad.

At the time, Napa was far from the wine paradise it is today. The farmers in the region mainly raised livestock or grew apricots, almonds and walnuts. Just a few dozen wineries scattered across the valley.

One of them, founded by Robert Mondavi in 1966, was just down the road. Mr. Mondavi came from a wine family and he became a mentor to an entire generation of Napa winemakers starting in the 1970s, including the Cakebreads.

With the advice of Mr. Mondavi pioneered Mr. Cakebread with many of the techniques that came to define the high-end Napa wines, especially with a lot of focus on the agricultural side of winemaking. Though he was a big fan of technology — he was one of the first to use a neutron probe to measure soil moisture — he also insisted on getting his hands dirty and getting up before dawn every morning to work in his vineyards.

“Every day there’s something new coming up, aerial photos, etc.,” he told The Santa Rosa Press Democrat in 2004, “but the only way to really know is to leave footprints in the vineyard. No tire tracks. Footprints.”

Cakebread Cellars sold its first wines, just 157 cases (1,884 bottles) of chardonnay made from purchased grapes, in 1974. At the same time, the Cakebreads planted sauvignon blanc vines on their new lot. It was a bold choice: The grape was largely unknown to American drinkers, and planting it in Napa was almost unheard of.

“When we put sauvignon blanc in it, everyone thought we were wrong,” Mr Cakebread told The Boston Globe in 1984. “But we decided to only make wines that we liked to drink because we would if they didn’t. to sell .”

It wasn’t a mistake. Along with Cakebread’s fruity yet balanced chardonnay, sauvignon blanc became a signature wine, and it helped fuel the variety’s rising popularity among American wine consumers.

Still, it took nearly two decades for the Cakebreads to devote themselves full-time to the winery; until then they worked in their garage in Oakland and commuted north on weekends. They eventually sold the garage in 1989 and moved to Rutherford.

Today, Cakebread is one of America’s most highly regarded wineries and regularly tops an annual poll by Wine & Spirits magazine of the most popular brands among leading restaurants. It manages 1,600 acres of land and says it sells about 100,000 cases a year.

Over time, Mr. Cakebread something of the role in itself that Mr. Mondavi had once played, mentoring young winemakers and leading the community around Rutherford. He was president of the Napa Valley Vintners Association (as were two of his sons, Bruce and Dennis), and many of his former employees now run their own wineries.

“Jack was this great sage,” said David Duncan, the chief executive of Silver Oak Cellars in nearby Oakville, which his father founded the same year Mr. Cakebread started his winery. “He was always so welcoming and so passionate about the community.”

John Emmett Cakebread was born on January 11, 1930 in Oakland. His father, Lester, owned Cakebread’s Garage, a repair shop, where his mother, Cottie, also worked.

His father also owned a farm in Contra Costa County, where he grew almonds, walnuts, and apricots, and where Jack worked as a boy, between shifts in the garage.

Jack attended the University of California, Berkeley, but did not graduate. He served in the Air Force during the Korean War, assigned to the Strategic Air Command as a jet engine mechanic.

After his military service, he returned to the garage, which he took over after his father retired. He also started with photography.

What started as a hobby turned into a hobby, especially after he started taking workshops led by landscape photographer Ansel Adams. Within a few years, Mr. Adams trusted Mr. Cakebread enough to let him teach some of his lessons.

Mr. Cakebread eventually caught the eye of an editor at Crown Publishers, who commissioned him to shoot the photos for wine enthusiast Nathan Chroman’s “The Treasury of American Wines.” When the book was published in 1973, it featured nearly every commercial winery in the country—all 130. Today, there are some 11,000.

It was the book project that Mr. Cakebread sent to Napa on that day in 1972, and it was the advance he received for it that brought in money for the down payment on the cattle ranch.

Mr. Cakebread shifted his creative focus to winemaking, but he never left photography: years later, he could still be found with a Minox camera around the winery.

Jack and Dolores Cakebread gradually withdrew from day-to-day management in the 2000s, handing over control to their sons Bruce and Dennis. But they stayed active: Ms. Cakebread hosted an annual workshop introducing chefs to winemaking, while Mr. Cakebread became a regular at business schools and lectured on winemaking.

Among his words of advice was patience.

“I’ve realized it’s going to do what it’s going to do again,” he told The Press Democrat. “I only worry about the things I can change, I don’t worry about what I can’t.”

Dolores Cakebread passed away in 2020. Mr. Cakebread leaves behind his sons, Dennis, Bruce and Steve; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.