Last May Sandra Rivera, CEO at chip giant Intel, received alarming news.

Engineers had spent more than five years developing a powerful new microprocessor to perform computing tasks in data centers and were convinced they had finally made the product right. But during a regular morning meeting to discuss the project, signs of a potentially serious technical error surfaced.

The problem was so troublesome that Sapphire Rapids, the code name for the microprocessor, had to be postponed – the latest in a series of setbacks for one of Intel’s most important products in years.

“We were pretty depressed,” said Ms. Rivera, an executive vice president in charge of Intel’s data center and artificial intelligence group. “It was a painful decision.”

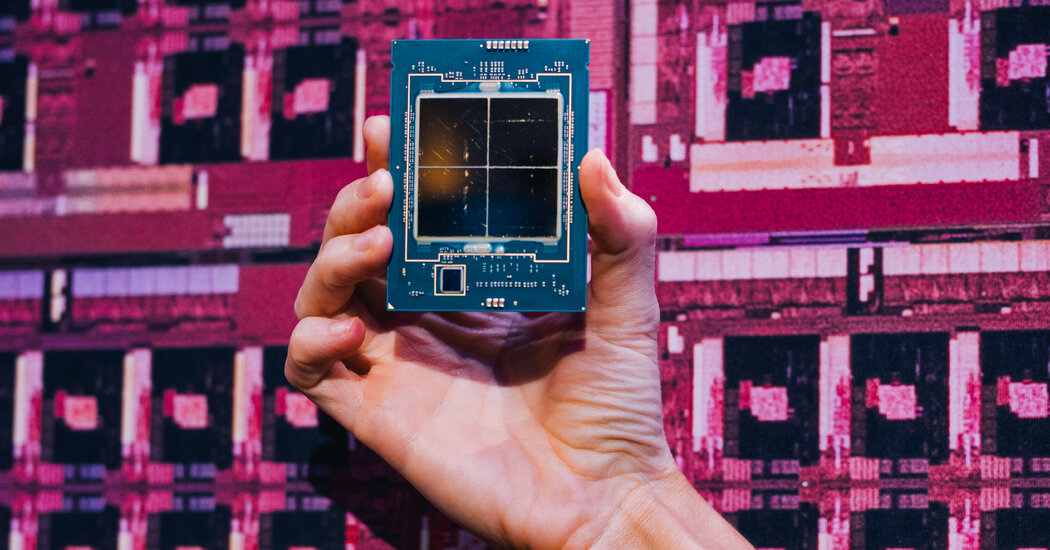

The launch of Sapphire Rapids was finally pushed back from mid-2022 to Tuesday, almost two years later than once expected. The protracted development of the product – which combines four chips in one package – underscores some of the challenges Intel faces as the United States tries to assert its dominance in basic computer technology.

Since the 1970s, Intel has been a leader in the tiny bits of silicon that power most electronic devices, best known for a variety called microprocessors that act as the electronic brains in most computers. But the Silicon Valley company has lost its long-standing lead in manufacturing technology in recent years, which helps determine how fast chips can compute.

Patrick Gelsinger, who became CEO of Intel in 2021, has vowed to restore his manufacturing lead and build new US factories. He was a leading figure as Congress debated and passed legislation over the summer to reduce US reliance on chip manufacturing in Taiwan, which China claims as its territory.

Sapphire Rapids’ bumpy development has implications for whether Intel can recover to deliver future chips on time. That’s a problem that could affect many computer manufacturers and cloud service providers, not to mention the millions of consumers using online services likely powered by Intel technology.

“What we want is a stable cadence that is predictable,” said Kirk Skaugen, the executive vice president in charge of server sales at Lenovo, a Chinese company planning 25 new systems based on the new processor. “Sapphire Rapids is the start of a journey.”

The pressure is high for Intel. In addition to declining demand for chips used in PCs, the company faces fierce competition in server chips, its most profitable business. That issue worries Wall Street, as Intel’s market value has fallen by more than $120 billion since Mr. Gelsinger took charge.

At an online event on Tuesday to discuss Sapphire Rapids, named after a section of the Colorado River, Intel customers detailed plans to use the processor, which they said would be particularly beneficial for artificial intelligence tasks. The product, formally called the 4th generation Intel Xeon Scalable processor, was introduced along with another delayed addition to the Xeon family of chips. That product, formerly codenamed Ponte Vecchio, was designed to speed up special tasks and was used alongside Sapphire Rapids in high-performance computers.

In an interview, Mr. Gelsinger said Sapphire Rapids had the makings of a hit despite the delays. He chose Ms. Rivera in 2021 to take over the development department, where she uses lessons from the experience to change the way Intel designs and tests its products. He said Intel had done several internal assessments of what happened to Sapphire Rapids, and “we’re not done yet.”

Sapphire Rapids started in 2015 with discussions among a small group of Intel engineers. The product was the company’s first attempt at a new approach to chip design. Companies now routinely put tens of billions of tiny transistors on each piece of silicon, but competitors like Advanced Micro Devices and others had started making processors from multiple chips bundled in plastic packages.

Intel engineers came up with a four-chip design, each with 15 processor cores that act as individual calculators for common computing tasks. The company also decided to add additional circuit blocks for special tasks, including artificial intelligence and coding, and to communicate with other components, such as chips that store data.

The interaction between so many elements is “very complex,” said Shlomit Weiss, who jointly leads Intel’s design engineering group. “Complexity usually brings problems.”

The Sapphire Rapids team struggled with bugs, flaws caused by design flaws or manufacturing defects that can cause a chip to miscalculate, run slowly, or stop functioning. They were also affected by delays in the product manufacturing process.

But by December 2019, the engineers had reached a milestone called “tape-in.” That’s when electronic files with a finished design move to a factory to make sample chips.

The sample chips arrived in early 2020, as Covid-19 enforced the lockdowns. The engineers soon got the compute cores on Sapphire Rapids communicating with each other, said Nevine Nassif, the project’s chief engineer. But there was more work than expected.

A major challenge was “validation,” a testing process in which Intel and its customers run software on sample chips to simulate computing tasks and find bugs. Once flaws are found and fixed, designs can go back to the factory to make new test chips, which usually takes more than a month.

Repeating that process led to missed deadlines. Ms Nassif said Sapphire Rapids is designed to counter AMD’s Milan processor, which was introduced in March 2021. But he wasn’t done yet in June, when Intel announced a postponement until next year to allow for more validation.

That’s when Mrs. Rivera intervened. The longtime Intel executive had successfully built a networking products business before being appointed chief people officer in 2019.

“We had to get our execution mojo back,” said Mr. Gelsinger. “I needed someone to run to the fire and solve this case for me.”

In October 2021, Ms. Rivera and a top designer hosted weekly Sapphire Rapids status meetings, held every Monday at 7 a.m. Those meetings showed steady progress in finding and fixing bugs, she said, bolstering confidence about production starting in Q2 2022. .

Then came the discovery of the flaw last May. Ms. Rivera wouldn’t describe it in detail, but said it affected the processor’s performance. In June, she took advantage of an investor event to announce a delay of at least a quarter, putting Sapphire Rapids ahead of the November launch of a competing AMD chip.

“We were ready to ship,” Ms. Nassif said. The final delay “was just so sad considering all the effort put into it.”

Ms. Rivera saw a series of lessons from the setbacks. One was simply that Intel put too many innovations into Sapphire Rapids, rather than delivering a less ambitious product.

She also concluded that the team should have spent more time perfecting and testing the design using computer simulations. Finding bugs before they’re in sample chips is cheaper and would have allowed features to be removed to simplify the product, Ms. Rivera said. She has since moved to bolster Intel’s simulation and validation capabilities.

“We used to have a lot of this kind of muscle that we let atrophy,” Ms. Rivera said. “Now we are rebuilding.”

She also found that Intel had planned more products than its engineers and customers could easily handle. So she streamlined that product roadmap, including pushing back a Sapphire Rapids successor to 2024 from 2023.

More generally, Ms. Rivera and other Intel executives have pushed the organization to develop better processes for documenting technical issues and sharing that information inside and outside the company.

Some Intel customers say communication has improved.

“Did everything go well? No,” said Mr. Skaugen of Lenovo, who once ran Intel’s server chip business. “But we were much less surprised than in the past.”