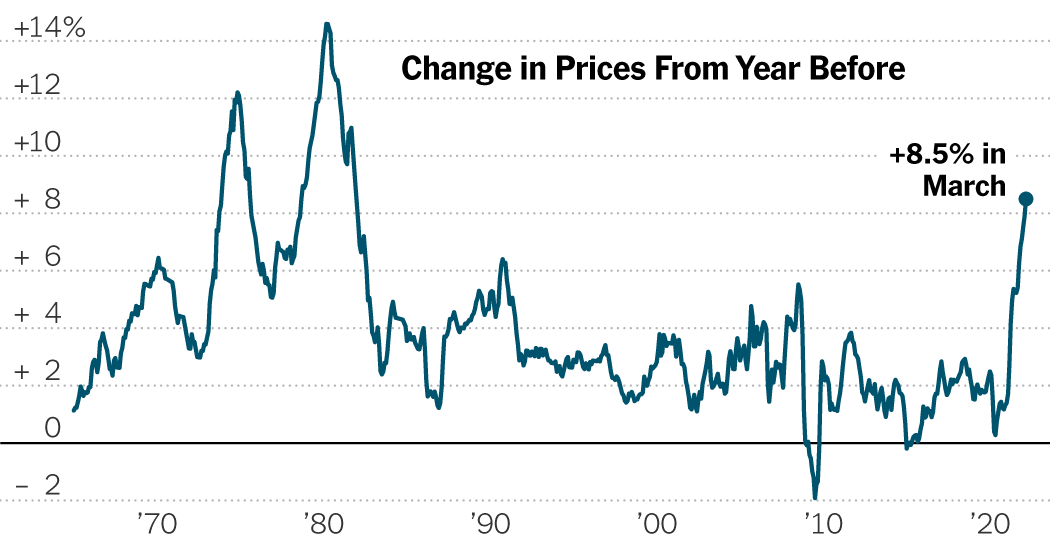

Inflation reached 8.5 percent in the United States last month, the fastest pace in twelve months since 1981, as a rise in gasoline prices linked to the Russian invasion of Ukraine sparked sharp increases following the collision of a strong demand and persistent pandemic-related supply shortages.

Fuel prices rose to record levels in much of the country and food costs soared, the Labor Department said in its monthly Consumer Price Index report on Tuesday. Price pressures have been painful for US households, especially those with lower incomes who spend a large portion of their budgets on necessities.

But the news wasn’t bad everywhere: A measure that will ease volatile food and fuel prices slowed slightly from February as used car prices swelled. Economists and policymakers took that as a sign that inflation in commodities could begin to cool after soaring at a breakneck pace for most of the past year.

In fact, several economists said March could be a high for overall inflation. The price increases could ease in the coming months, in part because gasoline prices have fallen somewhat — the national average for a gallon was $4.10 Tuesday, according to AAA, down from a peak of $4.33 in March. Some researchers also expect consumers to stop buying so many goods, be it furniture or outdoor equipment, which could put pressure on overstretched supply chains.

“These numbers probably represent a spike,” said Gregory Daco, chief economist at Ernst & Young’s strategy consulting firm, EY-Parthenon. Still, he said, it will be crucial to see whether price increases excluding food and fuel – so-called core prices – slow down in the coming months.

A hiatus would be welcome news for the White House, as inflation has become a major burden for Democrats as the November midterm elections approach. Public confidence in the economy has plummeted, and as rapid price increases undermine support for President Biden and his party, they could jeopardize their control of Congress.

While inflation is rising in much of the world as economies adjust to the pandemic and share supply chain problems, core prices in the United States have risen more than in places like Europe and Japan.

That has made Republicans a talking point, especially as prices are overwhelming recent wage growth. Average hourly wages rose 5.6 percent in March, according to the Labor Ministry. But adjusted for inflation, the average wage fell by 2.7 percent.

“Americans’ Salaries Are Worth Less Every Month,” Pennsylvania Republican Senator Patrick J. Toomey wrote on Twitter after the report.

Understanding inflation in the US

While the Federal Reserve has primary responsibility for controlling inflation, the government has taken steps to curb price increases. Mr Biden announced Tuesday that a summer ban on the sale of higher-ethanol gasoline blends would be suspended this year, a move White House officials say aimed at lowering gas prices.

The move followed the president’s decision last month to release one million barrels of oil per day from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve over the next six months.

“I am doing everything in my power, by executive order, to lower prices and deal with Putin’s price hike,” Mr Biden said Tuesday afternoon in Iowa, referring to Russia’s President Vladimir V. Putin. Inflation had risen sharply before the war in Ukraine, although the conflict has increased pressure on energy and commodity prices.

There are some hopeful signs that inflation could slow down in the coming months.

The first is largely mechanical. Prices started rising last spring, meaning changes in the coming months will be measured against a higher figure from a year ago.

More fundamentally, the March data showed that prices for some goods, including used cars and clothing, were moderating or even falling – although the signal was somewhat inconsistent, with furniture prices rising sharply. If the rapid inflation of prices for goods does indeed decrease, it may contribute to a decrease in overall inflation.

“It’s very welcome to see moderation in this category,” Lael Brainard, a Fed governor and Mr Biden’s candidate to become the next deputy chairman of the central bank, said in an online appearance hosted by The Wall Street Journal. “I’ll see if we continue to see moderation in the coming months.”

Between the slowdown in gasoline prices this month and a possible easing in commodity prices, even economists who have long expressed concerns about inflation said it could begin to ease.

“There’s a good chance we won’t see a figure above 8.5 percent this year,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard economist who chaired President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers.

But even if inflation slows slightly, it will likely be well above the Fed’s target by 2022, which it defines as an average of 2 percent based on a related but more decelerated price index.

The crucial question is how much and how quickly prices will fall, and recent developments increase the risk that uncomfortably rapid inflation could continue.

The costs of services, including rent and other housing costs, are rising faster. These measures are slow and will probably be an important factor determining the course of inflation.

Frequently asked questions about inflation

What is inflation? Inflation is a loss of purchasing power over time, meaning your dollar won’t go as far tomorrow as it did today. It is usually expressed as the annual price change for everyday goods and services such as food, furniture, clothing, transportation, and toys.

Wages are rising sharply, raising costs for employers and possibly inciting them to increase prices. Companies may feel they have the power to pass on increasing costs to customers, and even increase their profits, because consumers have spent an entire year of rapid price increases.

And cheaper goods are not guaranteed. An outbreak of the coronavirus is closing cities and disrupting production in China, and the war in Ukraine is creating a huge dose of uncertainty over raw material prices and supply chains.

“The impact of these commodity price shocks could take some time to make their way through the economy,” said Tim Mahedy, senior economist at tax and consulting firm KPMG US.

After a long period of rapid inflation, the US central bank is reacting, rather than waiting to see what happens next. Fed officials began raising interest rates last month and have indicated they will continue to raise them “quickly” as they try to rein in lending, spending and demand in the hopes of preventing precipitous price increases from become a more permanent feature of the US economy .

“It was a shock: We went for a decade where we couldn’t get inflation to 2 percent,” Christopher J. Waller, a Fed governor, said at an event on Monday. “We hope it will go away relatively soon, that’s our job and we’re going to get it done.”

Policymakers are expected to implement a half-point rate hike at their meeting in early May, and have indicated that they will soon begin a rapid cut in bond holdings, a change that should bolster higher rates and reduce demand. Ms Brainard suggested on Tuesday that such a plan could be announced as early as May and could go into effect as early as June.

While forecasting consumer demand to decline in the coming months as the government provided less financial aid to households than in 2021 and as borrowing costs rose, Ms Brainard cited the war in Ukraine and Chinese lockdowns as risks that could curtail supply. and could curb inflation. increased.

In a recent Bloomberg survey of economists, the average inflation forecast for the last three months of this year was 5.4 percent from the previous year — well above the Fed’s target. Businesses and consumers regularly say that rapid inflation is disrupting their economic lives, with many expressing concern that it will not evaporate soon.

“Even if the economy is slowing down, it doesn’t feel like it’s slowing down for the builders, for people who have construction products, for the transportation companies,” Crissy Wieck, chief sales officer at the transportation company Western Express, said during a Fed-hosted panel on Tuesday. Monday.

She noted that truck drivers typically buy trucks when the demand for transportation is as high as it is today, lured by the promise of high pay — but due to a truck shortage, that extra capacity could take years.

“That supply chain and the supply-demand relationship isn’t going to correct,” she said.

Ben Casselman and Ana Swanson reporting contributed.