Tourists in Indonesia are still trying to recover from the devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Now the country’s parliament has passed new laws that some fear could once again turn tourists away – as extramarital sex will soon be banned.

The controversial laws, which critics have labeled a “disaster” for human rights, also prohibit unmarried couples from living together and limit political and religious freedoms. There were protests in Jakarta this week and the laws are expected to be challenged in court.

The new penal code will come into force in three years and will apply to Indonesians and foreigners living in the country, as well as visitors.

It has been widely reported in nearby Australia, where some newspapers have dubbed it the “Bali bonk ban”.

Some observers say the new penal code is unlikely to affect tourists because any prosecution would require a complaint by the children, parents or spouse of the accused couple.

But a Human Rights Watch researcher said there could be circumstances where the new code “will pose a problem.”

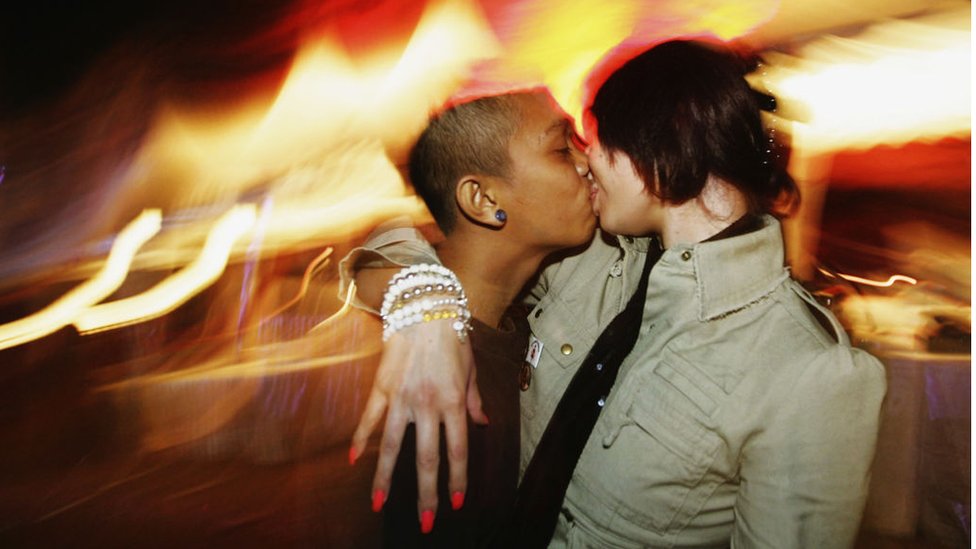

Indonesia’s economy relies heavily on tourism from Australia, which was Indonesia’s main source of tourism before the pandemic. Thousands of people fly to the tropical island of Bali every month to enjoy the warm weather, enjoy cheap Bintang beers and romp at all-night beach parties.

Weddings in Bali are very common, and thousands of Australian students fly to Bali every year to celebrate finishing high school.

For many young Australians, a trip to Bali is seen as a rite of passage. Others go there a few times a year for quick, cheap getaways.

As soon as news trickled in that the series of new laws became a reality, after years of mere rumours, some doubts about future travel set in.

On Facebook pages dedicated to tourism in Indonesia, users tried to understand the changes and what they mean for foreign visitors.

Some said they would travel with their marriage certificates, while others who weren’t married said they would go elsewhere if the law says they can’t share a hotel room with their partner.

“You will bribe your way out,” said a user from the Bali Travel Community group.

“A good way to ruin Bali’s tourism industry,” wrote another, while others agreed it was a “scare tactic” that would be impossible to enforce.

Australians need not worry

The new penal code means that – if a complaint is first filed by the children, parents or spouse of the accused couple – unmarried couples who have sex could face a prison sentence of up to one year and those who cohabitation could receive a prison sentence of up to six months.

A spokesman for the Indonesian Ministry of Justice tried to allay concerns by suggesting that the risk to tourists was reduced because anyone filing the police complaint would most likely be an Indonesian citizen.

That means Australian [tourists] shouldn’t worry,” Albert Aries told Australian news website WAToday.com.

But critics say vacationers could fall into the trap.

“Say an Australian tourist has a boyfriend or girlfriend who lives locally,” Andreas Harsono, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

“Then the local parents or the local brother or sister have reported the tourist to the police. That will be a problem.”

The argument that police only investigate if a family member files a complaint is dangerous in itself, Harsono said, because it opens the door to “selective law enforcement.”

“It means it will only be implemented against certain targets,” he told ABC radio.

“It could be hotels, it could be foreign tourists… allowing certain police officers to extort bribes or certain politicians to, say, use the blasphemy law to jail their opponents.”

While much of the chatter online reflected Australia’s attitude of “don’t worry, mate”, there is still a strong undercurrent of concern.

Australians are well aware of how serious it can be to get into trouble with Indonesian authorities – even for relatively minor offences.

But Bali cannot afford to deal another blow to the tourism sector. The recovery from the pandemic is slow and many businesses and families are still trying to get back what they lost.

In 2019, a record 1.23 million Australian tourists visited Bali, according to the Indonesia Institute, a Perth-based non-governmental organization.

Compare that to 2021 — when just 51 foreign tourists visited the island year-round because of the pandemic, Statistica’s data shows.

However, Indonesian tourism is picking up – in July 2022, Indonesia’s National Bureau of Statistics recorded more than 470,000 foreign tourists arriving in the country – the highest number since the easing of Covid-19 restrictions last October.

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch tweeted that the new laws will “blow up tourism in Bali”.

‘I really depend on tourism’

A guide named Yoman, who has been working in Bali since 2017, told the BBC that the impact of the new laws could be “very serious” across Indonesia, but especially on the resort island.

“I am very worried because I really depend on tourism,” he said.

Bali has a history of events – both man-made and natural disasters – that have affected the island’s visitor numbers.

“The Gulf War, Bali bombings, volcanic eruptions, Mount Semeru (volcano), Mount Rinjani (volcano) and then Covid. Bali tourism is easily affected,” said Yoman.

But the Indonesian government has taken initiatives to try to lure foreigners back to its idyllic shores.

Just a few weeks ago, it announced an enticing new visa option, allowing people to live on the island for up to 10 years.

And of course not only tourists from Australia can be affected.

Canadian travel blogger Melissa Giroux, who moved to Bali for 18 months in 2017, told the BBC that after years of talking she was “shocked” that the law was actually being passed.

“Many tourists will prefer to go elsewhere rather than risk going to prison once the law is in effect,” says Giroux, who writes the blog A Broken Backpack.

“Not to mention the singles who come to Bali to party or those who fall in love during their travels.”