Imagine starting to pedal from the start of stage 12 of this year’s Tour de France. Your very first task would be to cycle approximately 33.2 km 20.6 miles to the top of the Col du Galibier in the French Alps, gaining about 1305 meters of elevation. But this is only the first of three big climbs in your day. Next, you’ll face the summit of the Col de la Croix de Fer and finish the 165.1km stage with the famous Alpe d’Huez climb with its 21 twisting turns.

On the fittest day of my life, I might not even be able to finish stage 12 — let alone in anything remotely close to the five hours or so it takes the winner to complete the ride. complete. And Stage 12 is just one of 21 stages to be completed in the 24 days of the tour.

I’m a sports physicist and I’ve modeled the Tour de France for almost two decades using terrain data – like what I described for stage 12 – and the laws of physics. But I still can’t fathom the physical abilities needed to complete the world’s most famous cycling race. Only a few elite people are able to complete a Tour de France stage in a time measured in hours rather than days. The reason they can do what the rest of us can only dream of is that these athletes can produce massive amounts of power. Power is the rate at which cyclists burn energy, and the energy they burn comes from the food they eat. And over the course of the Tour de France, the winning cyclist burns the equivalent of about 210 Big Macs.

Cycling is a game of watts

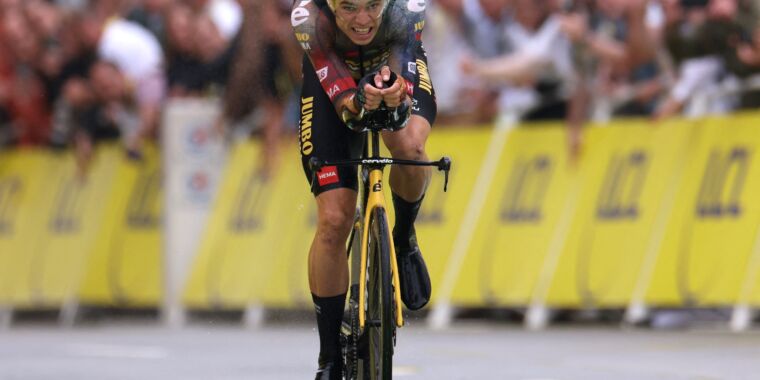

To make a bike move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bike, and to the wheels pushing back on the ground. The faster a rider can deliver energy, the greater the power. This rate of energy transfer is often measured in watts. The Tour de France cyclists are capable of generating massive amounts of power for an unbelievably long time compared to most people.

A fit recreational cyclist can deliver 250 to 300 watts continuously for about 20 minutes. Tour de France riders can produce more than 400 watts in the same period. These pros are even capable of hitting 1000 watts for a short time on a steep incline — about enough power to run a microwave.

But not all the energy a Tour de France rider puts into his bike is converted into forward motion. Cyclists fight against air resistance and friction losses between their wheels and the road. They get help from gravity on descents, but they have to fight gravity while climbing.

I integrate all the physics related to the cyclist’s power, as well as the effects of gravity, air resistance and friction into my model. Using all of that, I estimate that a typical Tour de France winner should deliver about 325 watts on average over the roughly 80 hours of the race. Remember, most recreational cyclists would be happy if they could produce 300 watts for just 20 minutes!

Converting food into kilometers

So where do these cyclists get all that energy from? Food of course!

But your muscles, like any machine, can’t convert 100 percent of food energy directly into energy output — muscles can be anywhere from 2 percent efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40 percent efficient at the heart. In my model I use an average efficiency of 20 percent. With this efficiency and the energy output needed to win the Tour de France, I can estimate how much food the winning cyclist will need.

Top Tour de France cyclists who complete all 21 stages burn about 120,000 calories during the race – or an average of nearly 6,000 calories per stage. On some of the tougher mountain stages, like this year’s Stage 12, racers will burn close to 8,000 calories. To make up for these massive energy losses, riders eat delectable treats such as jam sandwiches, energy bars, and delectable “gels” so they don’t waste energy chewing.

Tadej Pogačar won both the 2021 and 2020 Tour de France and weighs just 146 pounds (66 kilograms). Tour de France cyclists don’t have a lot of fat to burn for energy. They have to keep food energy in their bodies so that they can expel energy at what appears to be superhuman speed. So this year, while watching a stage of the Tour de France, pay attention to how often the cyclists eat — now you know the reason for all that snacking.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. You can subscribe to The Conversation newsletter here.

![]()